If you’re a mature, experienced weight trainer and you’re noticing more aches and pains lately, you may be wondering if your workouts are part of the problem. If your experiences are similar to mine, they probably are.

What I learned from my own ruptured biceps may help you avoid injury. I’ll explain what happened, what I did about it, and leave you with an idea of how to make your own training easier on your joints.

Me – back in my bodybuilding days

A Little Background

Weight training started for me in the mid-1970s as part of high school wrestling. I slowly got drawn into the magazines, the gyms, and the new-at-the-time Nautilus machines. I was more of a recreational athlete than a competitive one. I did a couple of bodybuilding competitions and a couple of triathlons, but those only punctuated my exercise through the years.

READ: 7 Reasons Your Injury Is Not Getting Any Better

In 1983, I was hired as a personal trainer at the Sports Training Institute in New York City. Certifications came later, first a CSCS and then CPT. I stayed in personal training in various formats, supervised trainers, and taught the personal training curriculum at some community colleges. This is all to say I had the paper and experience to think I knew what I was doing.

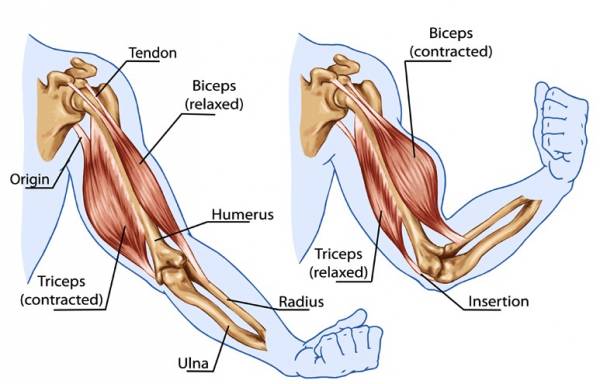

Just prior to my fortieth birthday, I was in my basement gym and had just started a set of slow curls when I felt a twinge at the back of my right shoulder. I put the weight down, pulled my sleeve up, and found a black-and-blue golf ball where my right biceps had been. I had a proximal biceps rupture.

What Was I Doing Wrong?

At the time, John Elway had recently experienced the same, so even with dial-up Internet information on the injury was easy to find. The first suggestion I found was “manage the pain.” Not an issue with me, since I wasn’t throwing a football eighty yards when it happened.

RELATED: The 2-Minute Arm Workout to Build Strong Biceps

The next recommendation was to not repair the injury. The thinking being the repair wouldn’t hold, and other muscles around the biceps would compensate anyway. The biceps has two attachments on the scapula, so one is expendable functionally. Aesthetically, not repairing the injury does make a difference. There’s a nice divot where the “peak” of my muscle had been, although that is less noticeable over time.

But in my research, the thing that got my attention was that the injury is common among sixty-year-old men – not 39-year-olds. What could I possibly have done to prematurely age my shoulders?

The Usual Suspects

At the time of the rupture, I was not lifting an especially heavy weight. I was not deadlifting, power cleaning, or bouncing off the bottom of chin ups, nor was I in the habit of doing those things.

“I concluded the accumulated wear and tear on the shoulders from years of working out must have frayed the tendon until it popped. It just reached the critical point during that curl.”

I did a simple standing curl in a slow cadence. I was not on antibiotics, and I do not and did not use anabolic steroids, HGH, or any other ergogenic. I didn’t pitch baseball or do any other sport excessively. Any of the obvious, direct causes of an acute rupture didn’t seem to apply.

READ: Male Body Image and the Pressure to Use Steroids

I concluded the accumulated wear and tear on the shoulders from years of working out must have frayed the tendon until it popped. It just reached the critical point during that curl. It could just have easily have happened while shooting baskets, doing yard work, or playing with my kids. I decided to review my first 25 years of exercise to see if there were things in my workouts that could be improved.

The Culprit: Excessive Range of Motion

At some point or another, I had dabbled with just about every kind of exercise. If they hurt in the wrong way, i.e. joint discomfort, as opposed to muscle burning, I generally got away from them before I became injured or used them judiciously. Press behind the neck, upright rows, side raises with the pinky up, Olympic lifts, and powerlifting all fell into this category. So while wear and tear may have accumulated, I didn’t do any suspect exercises consistently enough to blame one of them in particular.

But the one mistake I consistently made was an excessive range of motion with chest work. No matter which chest exercise I did, I allowed the weight to push my upper arms as far back behind me as possible. Due to the notions and cues of “full range of motion” and “touch the bar to your chest,” I thought there was some magic benefit to loading that overstretched position. I later found out it’s a good strategy for creating anterior instability, which turns out to be a bad idea if you like healthy shoulders.

“A vulnerable joint position is just that, whether you see it in sports, manual labor, martial arts, or your workout. Exercise isn’t exempt.”

At the time, that overstretch jumped out at me as the most obvious discomfort I had experienced during my workouts, so I assumed that was the culprit in accelerating twenty years of wear and tear. When I went back to training, dips and push ups, barbell and dumbbell presses, and dumbbell flyes all went on hiatus. I only did machine chest work if I could set a range limiter. Gradually I worked back up and got to where I could do all the exercises without discomfort, although with a much reduced-range than previously.

Give Your Joints a Break

If you suspect something in your workout is adding to your joint aches, you’re probably right. A vulnerable joint position is just that, whether you see it in sports, manual labor, martial arts, or your workout. Exercise isn’t exempt. The good thing about exercise is you can control the positions you put your joints in better than in those other activities.

“You may have to put aside trying to beat your personal records, and concentrate instead on the appropriate muscle action.”

Later that same summer, I fell while skating, landed on that same arm, and ruptured the triceps. At that point, I committed fully to a joint-friendly approach to training. I immersed myself in anatomy, biomechanics, and rehabilitation texts, eventually creating my own body of work on the subject (videos, manuals, blogs, talks), and that is now the exclusive approach I use on myself and clients.

RELATED: Why Your Mobility Work May Be Harming You

If you’re having some joint discomfort and you’ve ruled out anything that needs to be treated medically, it may be as simple as modifying or omitting an exercise. Look at every exercise you do and compare it to textbook muscle and joint function, and consider these general tips:

- Prevent the weight from pushing you into a painful range or an over-stretch position, even if it means using a shorter range.

- Deliberately stabilize your joints during a set, so the prime movers push against a stable, internal platform.

- Use enough weight to challenge the larger prime movers, but not so much that the deeper muscles are forced out of posture.

- In addition, you may have to change your attitude temporarily. You may have to put aside trying to beat your personal records, and concentrate instead on the appropriate muscle action.

It’s certainly viable to take a break from the more vigorous activity and work in a cycle of joint-friendly training. You’ll give your joints a break, you’ll stay in striking distance of top shape, and when the time comes, you can always go back to the more competitive approach. You can’t always fix a biceps, though.

Photos 2 and 3 courtesy of Shutterstock.