It is common knowledge that for strength, you must work sets in the 3-5 RM range more than any other. Similarly, doing many sets with high reps will get you huge. You can stretch your muscles if you get a big enough pump going. Consume at least 2g of protein per pound of body weight every day or you will always be a skinny loser.

Broscience is everywhere in the training world. Broscience, as defined in the urban dictionary, is “the predominant brand of reasoning in bodybuilding circles where the anecdotal reports of jacked dudes are considered more credible than scientific research.”

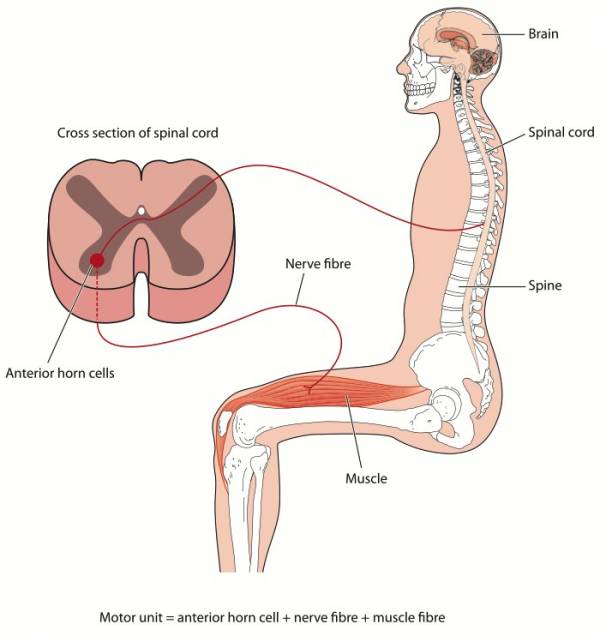

Scientists are more concerned with how things really are. They carefully design and painstakingly execute studies to find out what is really going on in our bodies when we train. They argue over the meaning of the results. They review each other’s work, and, when enough of them agree, the findings are published. That is how the Henneman size principle came to be. The Henneman size principle states that motor units are recruited in an orderly manner from smallest to largest, and that recruitment is dependent on the effort of the activity.

Unfortunately, how that information is used cannot be controlled. The widespread misapplication of the Henneman size principle, leading to the popular but unsupported belief that heavier-is-better for strength training, is an excellent example of broscience picking up where the research left off.

An important premise in strength training is that a motor unit (what muscles consist of) can only strengthen and grow when used. Hearing this, your bro, who knows all about the Henneman size principle, tells you that if you want to get stronger, you should pick up really heavy things. This faulty inference has led to claims that the Henneman size principle supports the 3-5 repetition maximum training intensity for greatest strength gain.

Some definitions:

- Force – a weight or pressure. Examples are: a barbell and pushing against the barbell

- Effort – how hard you are trying to develop force with your muscle

- Intensity – expressed a maximum number of repetitions or a percentage of the one-rep max, how difficult a given force is to resist

- Motor Unit – a group of muscle fiber bundles all attached to the same neuron

A simple way to illustrate how force and effort differ is with a single dumbbell. Let’s say it’s a 40lb dumbbell, and I ask you to perform an isometric hold at the halfway point in a dumbbell curl. It doesn’t matter how long you hold it, it will continue to weigh 40 lbs. The force you are producing is a steady 40lbs (for a while, anyway.)

A simple way to illustrate how force and effort differ is with a single dumbbell. Let’s say it’s a 40lb dumbbell, and I ask you to perform an isometric hold at the halfway point in a dumbbell curl. It doesn’t matter how long you hold it, it will continue to weigh 40 lbs. The force you are producing is a steady 40lbs (for a while, anyway.)

The effort you are putting into holding it there, however, will clearly increase over time. I can tell by the look on your face. At some point, the external force (which hasn’t changed) will overcome your effort, and you will lower the dumbbell. All the muscle fibers involved in flexing your elbow have failed. Would this experiment look any different if I handed you a 20lb or an 80lb dumbbell? No, with the likely exception of how long you could hold it. Otherwise, it would play out the same way.

Effort results from electrical stimulation of motor units (i.e. a decision to apply effort and generate force) and not the externally applied force. Interpolated Twitch Technique (ITT) is a way to measure muscle activation by applying an electrical current to a muscle already under Maximal Voluntary Contraction (MVC.) If any additional force is detected upon applying the supramaximal electrical stimulus, then it is concluded that the MVC was not a true maximal contraction. In other words, the muscle still had some strength left to give that the owner could not voluntarily elicit.

Scientists asked groups of old and young men to exercise at specific intensities and with specific time-under-tension. When they compared muscle activation and force development using ITT, what they discovered confirmed that the intensity of effort, not the external load, determines force output. No matter the intensity (5RM, 10RM, or 20RM) and time under tension (35, 70, and 140 seconds, respectively), no significant differences in motor unit activation occurred. Greater resistance did not have any effect on muscular activation. Their conclusion, verbatim: “the commonly repeated suggestion that maximal strength methods [resistance heavier than 6RM] produce greater neural adaptations or increases in neural drive was not substantiated in this study.”

The take-home message is this: motor unit recruitment depends on stimulus from the brain, not application of weight. It is absurd to cite the Henneman size principle when making repetition range prescriptions for strength or hypertrophy goals. So why is it done?

The take-home message is this: motor unit recruitment depends on stimulus from the brain, not application of weight. It is absurd to cite the Henneman size principle when making repetition range prescriptions for strength or hypertrophy goals. So why is it done?

The strange truth is that, for all we know, 3-5 reps @85% of 1RM might be the prescription for fastest and/or greatest strength gain, but it might not be. The experiments done regarding the Henneman size principle have been widely misinterpreted, and the bulk of textbooks on the subject use this erroneous interpretation. Assuming that our original premise, that a motor unit grows and strengthens when used, is true, and that motor units fire from smallest to biggest as effort, not external force, increases, any weight that can elicit momentary failure should be effective for increasing strength.

At first blush, this seems like madness. Then again, consider the common term “farmer strong.” Hand-loading 600 bales of hay makes a person strong, but if each bale is only 70lbs and the farmer can deadlift 400lbs (intensity=17.5% 1RM), how is that possible? Consider the highly effective Wendler 5/3/1 strength training system. The first two work sets of the day are essentially heavy warmup sets followed by one work set to failure (fire every motor unit, use the entire muscle). Consider gymnasts and others using bodyweight as their only resistance. These people become extremely strong, often without any regard, or even knowledge, of the relative intensity of each repetition.

Knowing what you know now, go back and read the books that you taught you what you “know” about strength programming. New questions come up.

References:

1. Ralph N. Carpinelli, “The Size Principle and a Critical Analysis of the Unsubstantiated Heavier-Is-Better Recommendation for Resistance Training,” Journal of Exercise Science & Fitness 2008, 6:2.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.