After years of roaming this big blue marble, I can conclude a few things. In general I find things work because doing something is better than nothing, and if you’re doing something, you might as well do it right. Given a choice to pound a nail into a piece of wood with four or five efficient strokes or eight to ten half-assed strokes, I’ll take the former.

It’s natural for things to evolve and change for the better. From the tethered-to-the-wall rotary phones to the current sleek smart phones, modern technology does make our lives better. But when it comes to human physiology, exercise, and nutrition, our bodies have not changed. What worked years ago still works today, but due to the inevitable “gotta find a better way” mentality (“cha-ching”), some things have been forgotten, ignored, or misunderstood.

Here are six facts that apply to most training programs in one way or another. If you’re on the right path and achieving your goals, that’s outstanding. But if you’re headed down the path of disappointment and lackluster results, maybe what follows will help you tweak a thing or two and reroute your efforts.

1. Power Development in the Weight Room

Improving power output is highly contingent on muscular strength. Increasing muscular strength through high-tension protocols (read: slower moving) improves your ability to express greater power. This is for the simple reason that being stronger means you’ll have more available muscle fibers to move any resistance relatively faster.

Training with heavier, but naturally slow-moving resistances increases strength. That is what is required to develop power. Lifting lighter resistances quickly, besides being potentially harmful to your muscles and connective tissues, results in fewer muscle fibers recruited and overloaded. It may be a demonstration of power, but not the best choice for developing power.

2. Speed Training

Most conventional speed-enhancing drills are not time worthy. The usual menu of slow-speed high knee, arm action, bounding, rear leg drive, skipping, or over stride drills contribute little to the act of running at full speed. Sprinting at 100% effort is a skill in itself. To run sixty or 100 meters at full speed requires the practice of moving your body as fast as possible over those distances.

And this applies not only to linear speed. If your spots requires you to move fast non-linearly and multi-directionally, practice the skills of it at full-speed. Legitimate motor learning research of sport specificity clearly suggests that exact replication of a skill is required. Performing a number of non-specific, slower-moving drills may be used as a part of a warm up routine, but don’t hang your hat on them to solely make you run faster.

3. Fat Loss and Aerobic Training

Are you aware the purest aerobic activity a healthy person can engage in is sleeping? Practically all of the energy to fuel your body aerobically during sleep comes from fat, but the body requires very little fat to do so. Pure aerobics is therefore a poor choice for fat loss. If you want to shed stored body fat, get out of bed and step up your exercise intensity.

Training in the traditional fat-burning zone (60-70% of your maximum heart rate (MHR)) is a much better option. Ironically, running for 45 minutes on a treadmill is considered aerobic training, which it is not, but it does requires the use of more energy substrate in the form of stored muscle glycogen, circulating blood glucose, and some fat.

Training at a higher intensity – 75-85% of your MHR – requires even more immediate energy, depletes muscle glycogen stores, and ultimately facilitates better fat burning post-exercise. The post-exercise recovery demand taps into body fat stores for many hours to facilitate recovery. All factors equal, training harder is the best option for losing body fat.

Training at a higher intensity – 75-85% of your MHR – requires even more immediate energy, depletes muscle glycogen stores, and ultimately facilitates better fat burning post-exercise. The post-exercise recovery demand taps into body fat stores for many hours to facilitate recovery. All factors equal, training harder is the best option for losing body fat.

4. Muscle Strength vs. Local Muscle Endurance vs. Cardio

Understanding the relationship between these three things could take pages and pages to cover all the details, but I’ll hit on main issues.

- Muscular strength is the ability of a muscle or group of muscles to exert maximum force in a single effort (i.e., a maximum resistance barbell bicep curl for a 1-repetition maximum).

- Local muscle endurance is the ability of a muscle or group of muscles to exert sub-maximum force over an extended period (i.e., a shoulder press with 100 pounds for 14 repetitions (reps) to volitional muscular fatigue).

- Cardiovascular endurance is the ability of the lungs, heart, vascular system, and skeletal muscles to interact as a whole to optimally support physical efforts over a lengthy period of time (i.e., running 1.5 miles or completing a 45-minute boot camp).

Increasing strength increases local muscle endurance. As mentioned earlier, the ability to progressively recruit more muscle (increased strength) allows for more potential reps to be performed in a given effort with a sub-maximal resistance (increased local muscle endurance). Case in point:

- Week 1: 1RM = 300 pounds

- 225 pounds (75% of the 1RM) for 13 reps

- Week 12: 1RM = 335 pounds

- 250 pounds (75% of your new 1RM) for 12 reps

After twelve weeks of progressive strength training the 1RM increased 35 pounds and 12 reps were performed with 250 pounds. If 225 pounds were used in the maximum rep set (the week one 75% of the 1RM resistance), naturally you could perform more than the 13 reps performed in week one. Your local muscular endurance improved as a result of becoming stronger.

Performing a series of local muscular endurance events with minimal rest time improves cardiovascular endurance. An example would be a 15 reps-to-volitional muscular fatigue total body circuit comprised of twelve different exercises and a 45-second rest between exercises (approximately a 20-minute workout). Individual muscles are overloaded, minimal rest is taken, and a number of sets are performed that tax the cardiovascular system.

The three energy systems – ATP-PC, glycolic, and aerobic – have interplay and function depending on the length and intensity of the exercise undertaken. It’s complicated, but to keep it simple just remember that becoming stronger improves local muscular endurance, and performing a series of local muscular endurance events with minimal recovery time between each augments cardiovascular endurance.

5. Muscle Fiber Classification

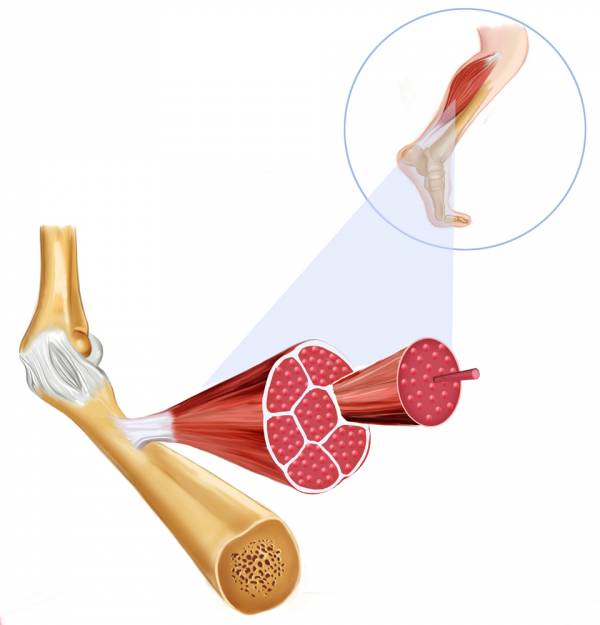

Humans have a variety of muscle fibers to get us through the various daily requirements we encounter, such as standing, walking, lifting, and climbing stairs. In general, these fibers have been termed slow twitch and fast twitch. A more accurate classification of fibers from slow to fast is types I, IC, IIC, IIAC, IIA, IIAB, and IIB.

Most people think what distinguishes the slow from the fast is the twitch, or contraction speed. That is true to an extent, but the terms slow and fast primarily refer to fatigue capacity, as in slow-to-fatigue type I muscle fibers and fast-to-fatigue type II muscle fibers. On one end of the continuum there are the slow-to-fatigue fibers for long-term, low efforts such as standing or typing on a keyboard. On the other end are the fast-to-fatigue fibers for short-term, high efforts such as maximal strength exertion.

Most people think what distinguishes the slow from the fast is the twitch, or contraction speed. That is true to an extent, but the terms slow and fast primarily refer to fatigue capacity, as in slow-to-fatigue type I muscle fibers and fast-to-fatigue type II muscle fibers. On one end of the continuum there are the slow-to-fatigue fibers for long-term, low efforts such as standing or typing on a keyboard. On the other end are the fast-to-fatigue fibers for short-term, high efforts such as maximal strength exertion.

Slow twitch fibers are smaller and contract slightly slower than fast twitch fibers, but not by much. In fact, many explosive movements activate primarily slow fibers due to a relatively low demand and the reality of Henneman’s Size Principle of muscle fiber recruitment.

Perform a vertical jump. It’s only your body weight you are moving (a relatively low demand). Yes, there is that explosive thrust through the ground, but because it’s low demand, many slow fibers are recruited. On a theoretical scale, fiber type recruitment it would look something like this:

Fiber type recruitment – body weight-only vertical jump for one jump:

- I – 40%

- IC – 45%

- IIC – 60%

- IIAC -35%

- IIA – 10%

- IIAB – 7%

- IIB – 3%

Add more resistance to the vertical jump and more fast twitch muscle fibers will need to be recruited. This would also be the case if you placed a heavy barbell (80% of 1RM) over your shoulders and attempted to perform the vertical jump. Interestingly, the heavier and slower-moving barbell would require the use of the larger fast twitch muscle fibers. It would move much slower than the bodyweight only vertical jump event. Again, theoretically, the recruitment scale would look something like this:

Fiber type recruitment – body weight + 80% of a 1RM for one rep:

- I – 50%

- IC -55%

- IIC – 70%

- IIAC -75%

- IIA – 80%

- IIAB – 70%

- IIB – 50%

It makes perfect sense if you think about it, but nomenclature can be deceiving. Heavy, but slow-moving equals better fast twitch fiber recruitment. Light, but fast-moving equals predominantly slow to intermediate twitch recruitment.

6. Lengthening, Sculpting and the Long, Lean Physique

Muscle lengthening: To lengthen a muscle, simply flex at the joint and then extend. In example, take your biceps. Flex (bend the elbow completely) then extend (straighten your arm completely). Congratulations, you have just lengthened the front of your arm to its maximum length. That’s it. If you want to make it longer, you’ll need to consult an orthopedic surgeon to move the muscles’ origins and insertions on the upper and lower arm bones. (I have never heard of anyone opting for that procedure.)

Muscle lengthening: To lengthen a muscle, simply flex at the joint and then extend. In example, take your biceps. Flex (bend the elbow completely) then extend (straighten your arm completely). Congratulations, you have just lengthened the front of your arm to its maximum length. That’s it. If you want to make it longer, you’ll need to consult an orthopedic surgeon to move the muscles’ origins and insertions on the upper and lower arm bones. (I have never heard of anyone opting for that procedure.)

Muscle sculpting: Overload the muscles to be sculpted via strength training exercises. Muscle will only grow (sculpt?) if exposed to intense stresses that involve the greatest amount of muscle fibers you possess. Other less-intense activities will not come close to good old-fashioned strength training.

The infamous long and lean physique: If you’re tall, you obviously possess long limbs. If you’re short, you obviously possess short limbs. For a long and lean physique, I hope you’re blessed with long limbs and low body fat. If you possess short limbs and minimal body fat, you would have a short and lean body. Sorry, but you cannot change that. If you believe surgically altering your muscle origins and insertions is difficult, imagine the task of lengthening your bones? That is impossible.

I hope this discussion was enlightening and assisted you in tweaking your training plan. I know reality sucks, but you need to be aware of the nonsense out there so you can implement a training program that is realistic and practical to your genetic endowment.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.