Functional training is a philosophy that both connects and divides much of the fitness industry. The largest issue I’ve seen with “functional training” is that it is actually more of a philosophically based means of training than one of agreed-upon specific methods.

Functional training is a philosophy that both connects and divides much of the fitness industry. The largest issue I’ve seen with “functional training” is that it is actually more of a philosophically based means of training than one of agreed-upon specific methods.

Where poses issues is in understanding what type of training is meaningful, what is circus like, what is innovative, and what is different for the sake of being different. That leads trainers and trainees alike into intense debates about many aspects of functional training – one of which is training planes of motion.

Training all the planes of motion isn’t as simple as it sounds.

Movement in Real Life

If you are unfamiliar, I’ll give a quick summary of planes of motion and how our training can best reflect real movement of the body. There are three planes of motion:

- Sagittal

- Frontal

- Transverse

Each joint can move in these planes, as well as the entire body itself. In order for our training to be functional, we need to truly understand how the body performs fundamental human motion. Actions like walking are a great example of how something simple in real life is quite complex upon examination. Our everyday action of walking uses all three planes of motion, producing and resisting forces all at the same time. Yet, we ignore many of theses concepts in our strength training.

“[W]e use the transverse plane to create some of our most powerful actions, like kicking, throwing, and punching. Given that, you might think it would be more integral to our idea of functional training.”

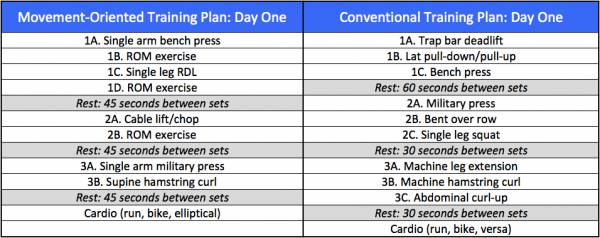

Some will argue this is not much a point of discussion. After all, doesn’t strength in general make us move better in every way? Well, a 2015 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research found that movement-oriented programs actually improved frontal plane stability of the knee and spine while conventional fitness programs did not.

This chart compares the movement-oriented exercises (left) with the conventional ones in the study (right).

Yes, sagittal work is important, it is our foundation. And most won’t debate the importance of the frontal plane, either. But how about that little transverse motion? I say that a bit sarcastically as we use the transverse plane to create some of our most powerful actions, like kicking, throwing, and punching. Given that, you might think it would be more integral to our idea of functional training.

The Debates

Ironically, transverse-plane training is hotly debated, but more from of a lack of understanding and knowing when to implement this form of training, rather than the training itself. Some coaches will even say you shouldn’t train the transverse plane because the risk involved with training it does not yield enough reward to warrant doing so. Are they right?

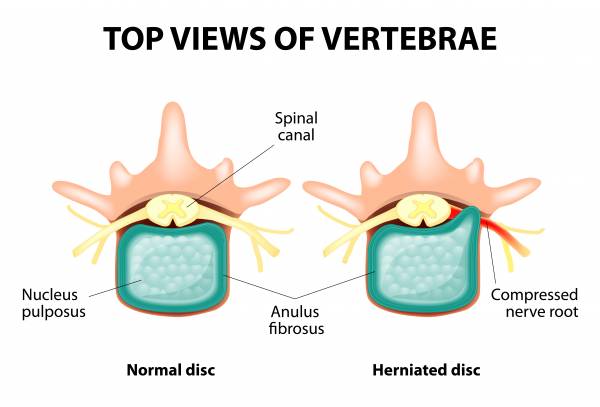

Well, it depends. If you are someone who believes rotational movements come from us twisting our torso, these coaches might have an argument. After all, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons has stated, “[T]wisting while you lift can also make your back vulnerable.” “Vulnerable” is referring to the risk of herniating discs in your back.

Rotational training needs to be smart in order to avoid disc problems.

Even if we take away the spinal flexion, just rotation of the torso can be tough. As leading researcher Dr. Stuart McGill stated, “…developing twisting moment places very large compression loads on the spine because of the enormous coactivation of the spine musculature. This can also occur when the spine is not twisted but in a neutral posture in which the ability to tolerate loads is higher.”

“You don’t have to be a scientist or a top strength coach to see how traditional rotation training might a problem. After all, who ever performed a set of Russian twists and thought their back felt awesome?”

Top strength coaches like Mike Boyle have long espoused concerns about the way most people perform rotational training. Coach Boyle cites the work of physical therapist and professor, Shirley Sahrmann. In her book Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes, she wrote:

[D]uring most daily activities, the primary role of the abdominal muscles is to provide isometric support and limit the degree of rotation of the trunk…A large percentage of low back problems occur because the abdominal muscles are not maintaining tight control over the rotation between the pelvis and the spine at the L5- S1 level.

That brings up an interesting idea that maybe our core isn’t meant to produce motion as much as it is meant to resist it. In their book, Mechanical Low Back Pain, physical therapists Porterfield and DeRosa stated, “Rather than considering the abdominals as flexors and rotators of the trunk – for which they certainly have the capacity – their function might be better viewed as antirotators and antilateral flexors of the trunk.”

You don’t have to be a scientist or a top strength coach to see how traditional rotation training might a problem. After all, who ever performed a set of Russian twists and thought their back felt awesome? Not many people I ever met!

The key to safe rotational training is assessment and safe progression.

The Rotational Debate

Of course in any debate there is an argument at the other extreme. Some believe because it is possible for our body to get in this position that we should train it. There are several issues with this thought process, though.

“The thoracic spine has 35 degrees of rotation and the hips have thirty to forty degrees of internal rotation. Based upon this relatively simple anatomy lesson, where do you think rotation should occur?”

The “you should rotate your spine under load” group will cite the need to teach movement in the SI joint and lumbar spine. Well, neither the SI joint nor lumbar spine possesses a great deal of movement. The SI joint, for example, possesses a whopping six degrees of motion. The lumbar spine? The greatest segment of rotation of the lumbar spine is at L5 and S1 – and is capable of degrees of rotation. Not much.

But don’t worry – all is not lost! The thoracic spine has 35 degrees of rotation and the hips have thirty to forty degrees of internal rotation. Based upon this relatively simple anatomy lesson, where do you think rotation should occur?

Is It Right for You?

In the video below, I will walk you through how you can qualify yourself to see if rotational training is right for you, how to do it well, and how you can easily progress the movements.

Qualifying Movements:

- Basic seated position

- Sandbag press out

- Sandbag rotational overhead press

- Horizontal medicine ball throw

- Sandbag rotational deadlift

- Kettlebell inside out clean

- Sandbag rotational clean

- Sandbag shoveling

More Like This:

- 3 Sandbag Exercises You Should Add to Your Training

- Sandbag Drills: Instability Builds Balance and Strength

- Kettlebells for an Iron Core: A 3-Phase Training Plan

- New on Breaking Muscle Today

References:

1. David M. Frost, et al, “Exercise-based performance enhancement and injury prevention for firefighters: Contrasting the fitness- and movement-related adaptations to two training methodologies.” J Strength Cond Res. 2015 Mar 10.

2. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, Herniated Disc in the Low Back,

3. Stuart McGill, Ultimate Back Fitness and Performance, McGill 5th edition (2004)

4. Shirley Sahrmann, Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes, Mosby (2001)

5. James Porterfield and Carl DeRosa, Mechanical Low Back Pain: Perspectives in Functional Anatomy, 2e, Saunders (2008)

Photo 1 by Edoarado (Own work), via Wikimedia Commons.

Information in chart courtesy of Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

Photo 2 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 3 courtesy of Jessica Bento.