Why do we even have a brain? Most people presume it’s to “perceive the world or to think,” but neuroscientist Daniel Wolpert says that assumption is completely wrong. The actual purpose of our brain is to produce adaptable and complex movements. Movement is the way we affect our environment and the world we live in. Nearly everything we do in life is a contraction of muscles: speech, gestures, walking, laughing, smiling, and athletic movements.

The Root of Movement Efficiency

The nervous system is made up of the brain, spinal cord, peripheral, nerves, and cranial nerves. With reference to athletic training, each component works together to mediate muscular action and govern the following systems:

- Cardio-Respiratory Training (aerobic and anaerobic cardio)

- Musculoskeletal Training (resistance training)

- Endocrine/Metabolism/Fat Loss Adaptations

The purpose of the nervous system is to create movement; therefore, the more efficiently it functions, the higher the quality of movement it produces. Movement efficiency is rooted in coordination, accuracy, and balance. Developing these qualities is the key to unlocking athletic performance, promoting resiliency, and preventing injury.

The nervous system has many “loops,” or neural pathways, to create, control, and coordinate movement. In this video series, Dr. Eric Cobb identifies three brain loops that are responsible for facilitating efficient movement. Let’s explore each of them, in detail.

The more efficiently the nervous system functions, the better your movement will be.

The Three Brain Loops: The Movement Loop

The movement loop has three primary actions:

- Receives sensory inputs. Eighty percent of the total sensory input comes from vision. The rest comes from the vestibular system (balance and head movement), and the proprioceptive sensors found in joints, muscles, soft tissue, skin, and organs.

- Integrates all inputs and makes decisions. The more closely the sensory signals match, the faster a motor decision is made. Optimal performance occurs when all sensory inputs are saying the same thing.

- Provides a movement output. The brain creates the best motor plan based on the information it is receiving. As movement occurs, new sensory information is created, thus repeating the process and allowing the nervous system to fine-tune the movement.

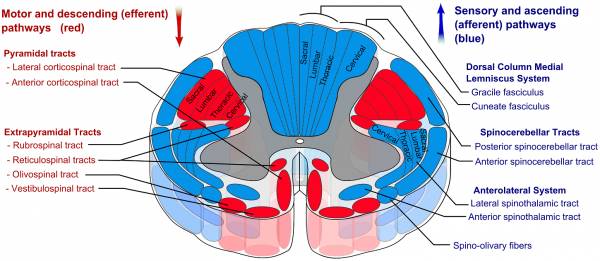

There are three neural pathways originating from the movement loop. They send messages downstream from your brain to directly control your muscles, and assist in the other loops as well.

- Corticospinal tract (CS): Provides the direct connection from the cortex (which initiates movement), through the spinal cord, to the motor units (nerves) that “switch on” the muscles. The CS tract only deals with voluntary movements.

- Reticulospinal tract (RS): Keeps the body stable and balanced during movement. This tract begins in the brain stem and receives inputs from the cortex, the vestibular system (balance sensors), and cerebellum (which handles coordination, motor learning, and balance).

- Miscellaneous sensory tracts: Multiple types of sensory information travel from the body to the brain along various tracts from the limbs through the spinal cord. Sensations caused by movement and joint position give the brain feedback about the movement that was just performed. Other sensory types, such as pain, temperature, and chemical sensations, inform our brain of our external and internal environments and help us adapt to potentially dangerous conditions.

The reticulospinal and corticospinal tracts make up two of the neural pathways of the movement system.

The Three Brain Loops: The Coordination Loop

The coordination loop compares what the cortex told the muscles to do with what the muscles actually did. Essentially, did the movement happen as it was intended? It also makes small adjustments to the movement plan when new sensory information is introduced, like when you shift your balance to catch a ball.

The Three Brain Loops: Preparation and Prediction Loop

The preparation and prediction loop (interoception) is how the body becomes aware of its own internal state and predicts future needs for maintaining homeostasis. Sensory information flowing into the insular cortex creates an internal representation of nearly everything happening in the body. This internal representation has the ability to change how we feel subjectively or how we think in order to direct our attention toward something that is not going right so that we may take corrective action.

Optimal performance occurs when there is minimal discrepancy between what the movement and coordination loops command, and what interoreceptive system reports back. Elite athletes have a high-level interoreceptive system, which prevents their brains from overreacting when faced with a physical challenge.

Bring the Brain Into Your Training

Many athletes and coaches are unaware of how their training impacts the nervous system, and vice versa. Accordingly, most do not consciously include the nervous system as part of their training, and the few who do typically focus on the CS tract. But about 90 percent of movement and posture is controlled reflexively, which means there is a lot of potential for improving stabilization, movement, and performance by ensuring the RS tract is functioning well.

Unilateral work will force your weak side to make positive neurological adaptations.

If you want to take advantage of the performance benefits of a well-trained reticulospinal tract, here are some ways to include the nervous system in your training:

- Include a sensory warm up in your training sessions.

- Include a variety of skill-based training in your program. Apply the principle of progressive overload. Through progressive skill-based training, your nervous system will learn how to manage and meet physiological demands.

- Include Vestibular Ocular Reflex (VOR) drills in your program.

- Train your eyes.

- Include individual joint mobility drills in your program.

- Do unilateral work to improve your weak side. Single-leg balancing with VOR and vision drills are highly effective.

- Use Heart Rate Variability (HRV) technology to measure your body’s parasympathetic output, or built-in “recovery mode.”

- Start tracking performance metrics. A low-tech notepad and pen work great. I also recommend using technology such as Train with PUSH when lifting to acquire power measurements. This can help you gauge changes in function within sessions and over time.

- Smile a lot, be happy, and laugh. Training with joy makes use of a few cranial nerves, including the cranial nerve that controls facial expressions and feeds into the reticulospinal tract.

The athlete with the best functioning brain wins because a better functioning nervous system creates better movement. Train your nervous system and watch your performance exceed your expectations.

More on Neurological Fitness:

- Your Brain on Movement: Challenge Your Nervous System

- The Critical Role of the Head and Eyes in Speed Training

- See It, Do It, Win It: Charge Up Your Visualisations

- New on Breaking Muscle Today

Photos 1 and 2 courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 3 courtesy of J Perez Imagery.