It’s only natural when starting an enjoyable, new activity that you want to learn more. These days, with people having Internet access in their pockets, it’s never been easier. Seriously, ask anyone how they learned things pre-Internet and you’ll hear about these wonderful things called libraries and books that had actual paper, but I digress.

When More Knowledge Is a Dangerous Thing

Even the most obscure activity will now have thousands of links you can follow to help you learn more. I can recall trying to learn more about weightlifting about twenty years ago and it was nearly impossible. Then dial-up Internet came about and suddenly it was easy to find plans, philosophies, and even competition results. These days you can just go to YouTube and watch greats like Klokov or Dimas lift or listen to a high-level coach give a podcast on the subject.

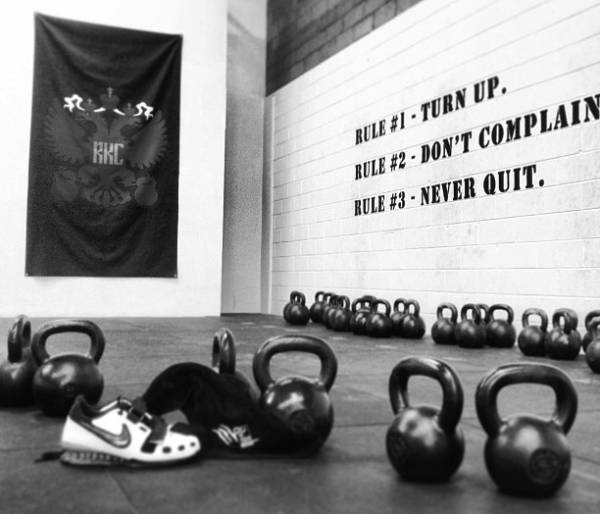

But this can be a problem. It’s rare that when you find this information that what people are talking about is what helped them at the beginning. A great example for me is when people want to get ready for RKC or SFG certification. Billed as “schools of strength” and with plenty of information from both groups on the best ways to train, they focus on lower-rep and high-load work, and on treating each lift like a weightlifter, focusing on the skill of the lift. The more strength and skill you have, the more you can display it by being able to use a higher load for the lift in question.

But that’s a great mistake if you’re getting ready to attend one of these events. I’m not saying don’t get stronger, far from it. Please save some bandwidth and don’t try to put words in my mouth if you’re planning on making a comment down below. What I am saying is that both weekends veer far more towards strength endurance than they do towards maximal strength.

Why You’re Going to Fail Your RKC or SFG Test

At my RKC, back when there was only a single choice, we hit over one thousand swings on the first day, with the vast majority of them done with double 24kg bells. For people unfamiliar with kettlebell work – that’s an awful lot of swings.

And taking gravity into account could mean the eccentric load on each swing was up to two to three times the weight of the bells. So that one thousand swings could have equalled something like 96,000kg of weight moved during the day.

Anyone who suggests there isn’t a massive strength endurance component involved in that needs to let go of the dogma and look at things more objectively. Further proof that it’s strength endurance that counts more than all-out maximal strength is present all through an RKC weekend. Plenty of people turn up really strong, but not really fit. And by the time testing comes along at the end of the weekend, they’ve pretty much run out of steam and often fail a portion, despite their impressive one-rep strength.

That even happens during the snatch test (100 reps with a 24kg bell in five minutes). I know a guy with a nearly 700-pound deadlift who struggles with the test because he doesn’t have the grip endurance, as he doesn’t train above three reps per set usually. Meanwhile, there are tons of people with deadlifts in the 300- to 400-pound range who crush that test, and all due to superior strength endurance.

Don’t Forget How You Got There

The problem happens when people higher up in the chain forget what they did to get in shape to attend the events in the first place. Partly understandable as in some cases it’s been many years since they had to certify or even test. And it’s not just limited to the fitness world, but happens in military selection, too.

Let’s imagine you’re off to BUD/S. (Good luck if you are, and much respect.) You need to be able to run four miles in wet pants and boots, on sand, in under 32 minutes for Phase One. You’re also expected to be able to knock out sets of twenty push ups all day long. I’ve read accounts of breakout (the start of Hell Week), which had candidates performing over 500 push ups and 1,000 flutter kicks along with many other exercises – in the first two hours.

So goal one if you’re off to BUD/S is enormous amounts of strength endurance. Going back a few years, it was six miles of running daily (a mile each way, for three meals a day) just to get chow. Total running for the day would easily total at least ten miles.

But do current, working SEALs need that kind of training? The few I speak with perform a lot of endurance training, but not enough for that kind of running, nor is their strength work even close to the sort of training that would get you ready for BUD/S.

Train Where You’re At

And this is one of the problems of programs you find on the Internet. These programs represent a snapshot in someone’s lifelong timeline of training. It may or may not be the same place that you’re at in your own personal training timeline. More than likely you’re looking for a plan that represents a point much closer to the beginning of that person’s timeline than what they’re up to now.

This is the main problem with advanced training plans. Everyone thinks they’re advanced, when usually they’re not even close. One of the SEALs I speak with can do over fifty strict pull ups in a set. So the first thing I’d suggest is that if you want to do what he does now for training, you need to focus on how to get to fifty pull ups. That means going back potentially years in his training. And clearly to get that kind of number you’d find there was a focus on strength endurance over maximal strength.

I’m not suggesting that you don’t do maximal strength, nor am I suggesting that strength endurance should be your top priority. I’m merely suggesting that if you’re a beginner looking to attend an event, race, or some other kid of test, that you follow an appropriate program for where you’re up to now – rather than try to follow something more in line with what Usain Bolt, Klokov, or a SEAL might follow. Trying to follow an advanced plan as a beginner is the number one rookie mistake.

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 courtesy of Read Performance Training.

Photo 3 by U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class Eric S. Logsdon [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.