This is the start of a series that will address a number of issues that men deal with and the hormones that affect their daily life. Today, we examine a few studies that may pique your interest in how certain movements can peak your testosterone more than others.

Chemistry and Endocrinology

Before looking into these studies, it is important to understand testosterone and its function in the body and brain. Testosterone is an androgen and is a type of lipid, or fat. In the lipid family, it is considered a steroid hormone.

Steroid hormones are composed of carbon atoms bound together into four ring-like structures. The organic structure of testosterone will not look the same as its other steroid hormone counterparts, like estrogen, but they do belong to the same family.

Testosterone and Body Function

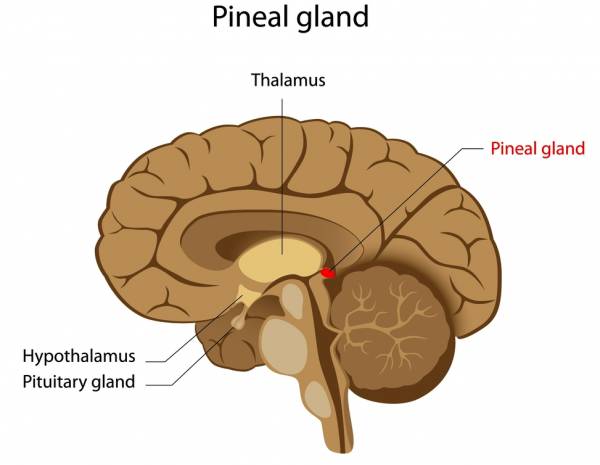

Testosterone has both direct and indirect effects on muscle tissue. It can promote growth hormone responses in the pituitary, which can influence protein synthesis in muscles. The potential interaction with other hormones demonstrates the highly interdependent nature of the neuroendocrine-immune system in influencing the strength and size of the skeletal muscles. The effects of testosterone on the development of strength and muscle size are also related to the influence of testosterone on the nervous system, specifically the pineal gland and anterior pituitary gland.

Even though we are mainly talking about testosterone, it’s important to talk about the other hormones that help in the release of testosterone from the testes, specifically luteinizing hormone (LH). LH is named for its functions in females, but has an important role in males. LH binds to the interstitial cells in the testes and causes them to secrete testosterone.

The Kettlebell Swing and Increased Testosterone

The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research investigated acute hormonal responses to the kettlebell swing movement using ten recreationally trained men (24±4 years of age, 175±6 cm, 78.7±9.9 kg). Each man performed twelve rounds of thirty seconds of 16kg kettlebell swings, alternating with thirty seconds of rest. Blood samples were collected before (PRE), immediately after (IP), fifteen minutes after (P15), and thirty minutes after (P30). Hormones that were analyzed included testosterone, growth hormone, cortisol, and lactate concentrations.

Since we are speaking of testosterone, we will go through those numbers specifically:

- Testosterone was significantly higher at IP than at PRE, P15, or P30. The numbers included the following: PRE 28÷3; IP 32±4, P15 29±3; P30 27± 3 nmol.

- Growth hormone was higher at IP, P15, and P30 than at PRE

- Cortisol was higher at IP and P15 than at PRE or P30

- Lactate was higher at IP, P15, and P30 than at PRE

The exercise protocol produced an acute increase in hormones involved in muscle adaptations, thus the kettlebell swing exercise might provide a good supplement to resistance training programs.

Hormonal Response to Free Weights and Machine Exercises

Similar to the study above, the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research conducted a study that analyzed acute hormonal response to free weights and certain machine exercises. This was done with the same conditions as the kettlebell study in regard to PRE, IP, P15, P30 and time of blood samples. Ten men (25 ± 3 age, 179 ± 7 cm, 84.2± 10.5 kg) participated in this study using similar lower-body multi-joint movement free weight and machine exercises. Each man completed six sets of ten repetitions of squat or leg press at the same relative intensity separated by one week.

The results of the study demonstrated:

Testosterone and Growth Hormone: significant increase at IP, but the IP concentrations at were greater for the squat than the leg press.

- Testosterone Squat Numbers: (31.4 ± 10.3 nmol?L(-1))

- Growth Hormone Squat Numbers: (9.5 ± 7.3 μ?L(-1)

- Testosterone Leg Press Numbers: (26.9 ± 7.8 nmol?L(-1))

- Growth Hormone Leg Press Numbers: (2.8 ± 3.2 μ?L(-1))

At P15 and P30 Growth Hormone was Greater at the Squat than the leg press

- Squat Numbers: (P15: 12.3 ± 8.9μ?L(-1)) (P30: 12 ± 8.9 μ?L(-1))

- Leg Press Numbers: (P15 4.8 ± 3.4 μ?L(-1)) (P30 5.4 ± 4.1 μ?L(-1))

Cortisol saw similar results, with an increase after exercise, but hormone levels were greater for the squat than the leg press.

The total work (external load and body mass moved) was greater for the squat than the leg press, but the rating of perceived exertion did not differ between the two. It can be inferred that free weights seem to induce greater hormonal responses to resistant exercises than machines using similar lower-body, multi-joint movements and prime movers.

The Growing Problem of Low Testosterone

According to the International Journal of Endocrinology, low testosterone is manifested in many ways including erectile dysfunction, low libido, loss of morning erections, depressed mood, and sleep disturbances. Men with low testosterone also showed less diurnal variation (levels of a substance in a 24-hour period) in their testosterone levels compared to younger men with normal levels of testosterone.

Obesity has a large impact on low testosterone. In obese males, levels of testosterone are reduced in proportion to the degree of obesity. To combat this, the first step in reducing visceral fat is dietary and lifestyle changes. Men are encouraged to combine aerobic exercise and strength training. With ongoing strength training, an increase in fast-twitch muscle fibers increases glucose burning capacity, which decreases insulin levels. Weight loss will increase levels of testosterone and should augment the affects of lifestyle and exercise advice.

The maintenance of biologically normal testosterone levels in males is fundamentally important to exercise adaptations and safe sport participation. One of the best ways to maintain your levels is by eating correctly and having the correct balance of strength and aerobic exercise. If you feel you need help with diet and exercise, seek out a nutritionist or exercise physiologist (exercise professional) to get on the right path to good hormonal health.

References:

1. Luigi, D et. al. “Andrological Aspect of Physical Exercise and Sports Medicine.” Unit of Endocrinology, Department of Health Science, University of Rome (2012): ePub, accessed May 19, 2014, PMID 22430368

2. Budnar, RG Jr. et. al. “The Acute Hormonal Response To the Kettlebell Swing Exercise.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (2014): ePub, accessed May 19, 2014, DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000474

3. Shaner, A et. al. “The Acute Hormonal Response to Free Weight and Machine Weight Resistant Exercises.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (2014): ePub, accessed May 19, 2014, DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000317

4. Hackett, G. et. al. “Testosterone Deficiency, Cardiac Health, and Older Men.” International Journal of Endocrinology (2014): ePub, accessed May 19, 2014, DOI: 10.1155/2014/143763

5. Tate, Philip. Seely’s Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. (New York: McGraw Hill Companies, 2012), 442-456, 780-821

6. Baechle, Thomas R and Earle, Roger W. Essentials of Strength and Conditioning, Third Edition. (Illinois: Human Kinetics, 2008), 52-54

7. McArdle, William D, et al. Exercise Physiology: Energy, Nutrition, and Human Performance, Sixth Edition. (Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007), 455, 437-450

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.