In 49BC, Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon River, which was considered an act of insurrection against Rome. Here he uttered the words, “The die is cast,” to suggest that crossing the river meant there was no return. What helps us cross our own “fitness Rubicons” and leads us to our point of no return? In an article in Psychological Science, researchers set out to describe one factor that might make us more persistent in our plans.

In some cases, we don’t have a choice when it comes to completing tasks. In business, we often need to finish a project or we get fired. These situations are called forced choices as we only have one option (to do the task). In this research, the forced choice was the control condition. Participants were asked to complete puzzles to get paid for the experiment.

The intervention condition was providing people with an option to quit at any time during the experiment. One might think that the option of quitting would lead people to give up early. However, the researchers found the exact opposite. People became more persistent in their work and solved more puzzles. Since the results were somewhat counterintuitive, the researchers conducted two additional studies varying the conditions to see whether the results would differ. However, when people had a choice to quit they tended to be more persistent and accomplished more.

Why the Option of Quitting Leads Us to Accomplish More

One potential reason for this result is that the option of not quitting led people to have to choose to continue. Once they made the choice to continue, the responsibility for the task fell on their shoulders and they felt more invested in the task. That is, they crossed the Rubicon and they had no way of going back. Thus, they became more invested.

Other research has shown that when people create their own goals they tend to follow them better than having when goals are given to them. For example, a person trying to quit smoking will do much better if asked, “How many fewer cigarettes do you think you can smoke per day?” As opposed to being told to cut down 10% for the week. That is, making your own goals is more effective than having someone else make them. Thus, when people are given the option to quit, they might feel like they have set the goal themselves to continue.

Another explanation is that people might have a certain amount of coercion sensitivity, which leads people to do the opposite when they think they are being coerced. I know exactly how to get my Mom to attempt an exercise she doesn’t think she can do. I simply tell her that it is probably too hard for her and she shouldn’t do it. For some people, being told they can’t handle something will lead them to try even harder. (Mom, if you’re reading this, please continue your kettlebell deadlifts.) For some people, being told it is okay to quit might raise their pride in wanting to finish the task.

The Take-Home

For coaches, the most obvious take-home is to try telling people that they always have an option to quit. When those individuals then don’t quit, they have just taken on the responsibility themselves (if they do quit, then we have another problem). Furthermore, we might get these clients to come up with their own goals instead of setting the goals for them. Sometimes it takes a bit of prodding and suggesting before people come up with their own goals, but once they do, make sure that they know it is a goal they set for themselves. Setting up their own goals leads to more ownership.

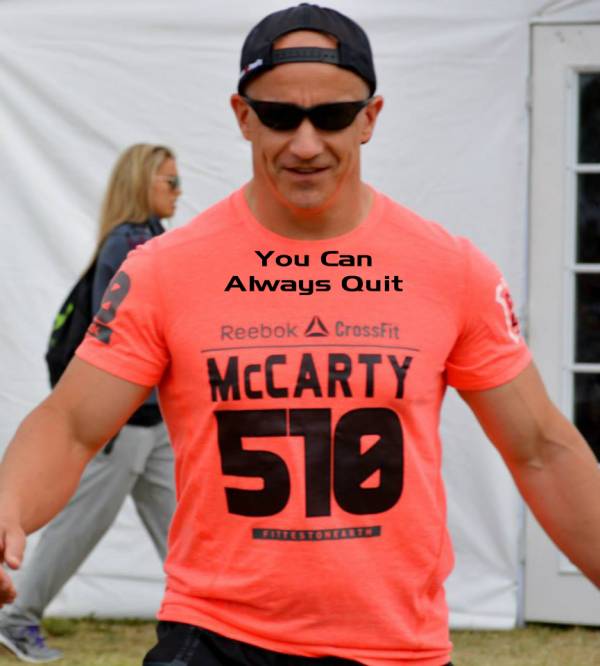

As individuals, we can remind ourselves of the reasons we set our goals. For example, if we are trying a new diet, we might first try to remember that we set this goal and the reasons why we set it. In the middle of a tough workout, we can tell our self that we can always quit and it is our choice to work out. I think it would be great to buy a t-shirt for a workout partner that tells me I could always quit. I would be quite motivated seeing him wear that shirt.

References:

1. Schrift, Rom Y., and Jeffrey R. Parker. 2014. “Staying the Course The Option of Doing Nothing and Its Impact on Postchoice Persistence.” Psychological Science 25 (3): 772–80. doi:10.1177/0956797613516801.

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 couresty of Patrick McCarty.