Should you run? If you are a triathlete then the answer is most surely yes. But what if you are a recreational or amateur cyclist? This week I’m exploring the pros and cons of running for cyclists. If you cycle for general fitness and fun, taking up running could be a good way to support your cycling.

I know what you are thinking – why not just cycle more? There are some specific aspects of running to consider.

A Case for Running

During a run, you shift your weight from one foot and leg to the other. Although this is not exactly the same motion as cycling, some of the similarities in movement will transfer across into cycling. Running is therefore a functional exercise for cyclists. One might argue that since the mechanical structure of the cycle restricts movement, running offers more in the way of everyday fitness and movement than cycling does.

Running is a good cardiovascular activity. It improves blood volume and strengthens the diaphragm and heart muscles. Both of these benefits will assist your ability to perform when cycling.

- Running helps develop balance skills and proprioception in the feet, ankles, knees, and hips, leading to quicker reaction times as your body has to continually adjust position. Proprioception and balance are important everyday skills that will also assist your cycling.

- Running requires you to actively unweight or lift the foot off the ground, using the hip flexors and hamstrings to take the next step. While cycling, it can be easy to develop a lazy leg, where one foot pushes the other up on the opposite pedal. This will mean that some of your energy is lost by lifting a heavy leg rather than propelling you along. Running will help activate the muscles required to unweight the rising leg. This leads to a more effective pedaling style.

- Running on trails requires you to lift your bodyweight quickly and use your legs as you travel over uneven ground. The landing and subsequent rapid extension of your legs will help them become more powerful.

- Running is an impact activity and cycling is not. Impact activities are good for developing bone density, which tends to decrease as you get older. I’ll return to this a little later.

- Running does not require much space. If you go out on your bike, you can cover quite a distance in the space of an hour, but you have to have access to a number of lengthy routes to follow. Running is done at a much slower pace. You can do an hour of activity just in your neighborhood, and you can also make use of paths that are not accessible to cyclists.

- Running can be a good postural activity. You may spend a significant amount of time seated at a desk all day. If you follow that with sitting on a bike, and your recreation consists of sitting at the table eating and then sitting again, you are likely to develop a sitting type of posture. Running demands that you stand and move while upright, which can help correct your postural habits.

- Running can be done anywhere and doesn’t require a bicycle or much gear. Several of my cycling associates travel in their daily work and often find themselves away from home overnight. Running gear does not take up much room in your bags, so you can do some useful training even while you are away.

When to Run

The demands of running are slightly different from cycling. The additional impact load may cause soreness in your legs at first. With any activity that is new or that you have not engaged in for a while, take things easy to start. Gradually build up duration and intensity. If you don’t run regularly, don’t be surprised if your hamstrings and calves ache after just thirty minutes of easy running.

“One might argue that since the mechanical structure of the cycle restricts movement, running offers more in the way of everyday fitness and movement than cycling does.”

Slotting a run in before an endurance ride works best for me. My legs will be sore after the run, but the low intensity endurance ride helps them recover. I don’t expect to break any records in my endurance ride, which should be performed at a medium intensity (no higher than eighty percent of your maximum). The non-impact nature of the reciprocating cycling movement will take your calves, quads, glutes, and hamstring muscles through a wide range of motion and increase blood flow to assist repair and recovery.

A weekly schedule could look like either of the following examples:

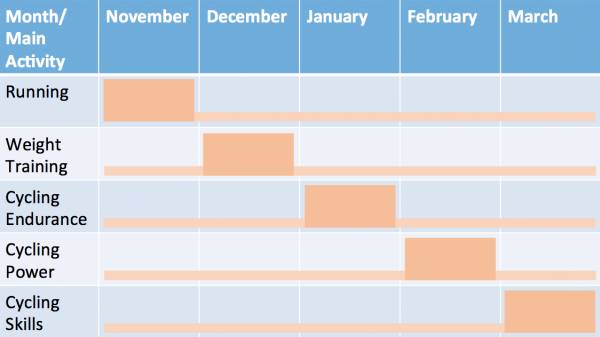

As winter starts to draw in, you could include a running period within your training program before moving back to cycling power or weight training sessions. The following chart shows an outline structure for winter training. The larger blocks show the main emphasis for each month. The smaller blocks indicate reduced levels of each activity in the other months.

What about Bone Density?

Returning to bone density, a study in 2003 compared bone density of cyclists in two different age groups with non-athletes of the same ages.1 The study found that the master cyclists who had been cycling for a number of years (and had not performed significant levels of weight bearing exercises) had low bone density. Chris Boardman is quoted as saying, “Cycling is good for strengthening muscles, but it does very little for bones.”2

Running Has a Place

As a masters athlete myself, I think the results of the study referenced above are important for overall fitness. Even if I were an out-and-out cyclist, I would run to avoid the degradation of proprioceptive skills and the risk of developing osteoporosis with advancing age.

More on running:

- The Runner’s Guide to Loving Gravity

- Flat Running Is Better Than Uphill Running

- 9 Things I Wish I’d Known When I Started Running

- What’s New on Breaking Muscle Today

References

1. J.F. Nichols, J.E. Palmer and S.S. Levy, Low bone mineral density in highly trained male master cyclists. Osteoporos Int. 2003 Aug;14(8):644-9. Epub 2003, Jul 11.

2.Chris Boardman quoted from Daily Mail article, 15 November 2009. Accessed Oct 14, 2015.