I recently sat down with Dr. Fred Hatfield, also known as Dr. Squat, to discuss his views on strength and conditioning and how they fit into modern training systems. For those of you unfamiliar, Dr. Hatfield was a great college gymnast and bodybuilder (he was Mr. Mid America, but he didn’t compete in the Mr. America competition because of a powerlifting meet).

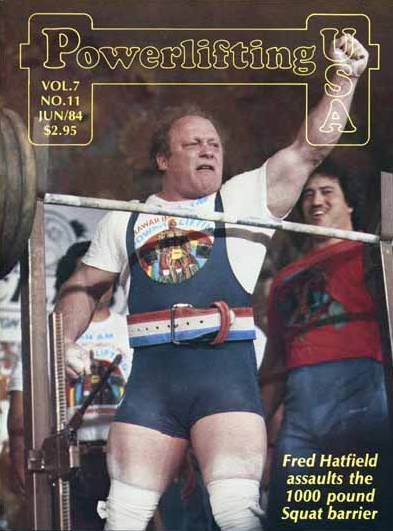

Dr. Hatfield is probably best known for his world record squat of 1,014lbs set in 1987 when he was the age of 45. He was also the founder of Men’s Fitness magazine and the International Sports Sciences Association, and he has written over sixty books. He knows squat and a whole lot more.

The 7 Laws of Training

Dr. Hatfield combed through a great deal of research to best improve his training. Here is what he had to say about seven common laws he found in successful training programs:

If something is called a law then it’s called a law for a reason. It means that you’ve just got to follow the law. If you break the law you go to jail or whatever; or you pay the consequences.

Many years ago, twenty-five or thirty years ago, people began to write about training a lot more than they had in the past, and I’m saying to myself how am I going to judge whether this training program is any good? I scoured the research literature and all of the popular literature for some kind of a yardstick to use to judge the efficacy of these training programs, because Lord knows I didn’t have the time or the energy to go on all of those programs.

In reading the works of many sports scientists, Hatfield boiled down their thoughts to seven fundamental laws that apply to all training (although some sports might have additional laws). These are the seven principles that guided him to squat 1,000lbs without the supportive suit technology available now for powerlifters. He indicated that these laws apply to all types of training and not only powerlifting.

1. The Law of Individual Differences

Everyone has different strengths and weakness, which need to be taken into consideration for the training program. No program fits all individuals. This realization really hits when looking at hip structure. In the picture below, the balls of the two femurs extend very differently. You can imagine that these two people will have very different squat mechanisms. The law extends beyond form and technique as people will have different levels of strength, recovery ability, coordination, and mobility to name a few.

2. The Overcompensation Principle

Our body reacts to stress by overcompensating, so that it can handle stress again in the future. This principle is why beginners at any sport see great improvement when starting their programs.

3. The Overload Principle

In order for your body to overcompensate, you must load it with a greater amount than was already encountered. This principle is the reason that people plateau in their gains over time. It becomes more and more difficult to stress the body to a point where it has not been stressed before.

4. The Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands (SAID) Principle

The basic tenet of this principle is that you must tax your body in the same way that you want to improve. If you want to be explosive, then you must train explosively. If you want to be strong, then you must train for strength. A simple example is the oft criticized high-rep Olympic lifts in CrossFit. These high-rep lifts may help in building aerobic or glycolytic capacity, but they will not assist in building Olympic weightlifting strength.

5. The Use/Disuse Principle and Law of Reversibility

The first part of this principle is that we must continue train the skill or we will lose that capacity (“use it or lose it”). However, the second part of this principle is that once it has been trained and lost, the skill (or strength) will be much easier to recover than it was to originally train. The idea is that we have laid a neurological foundation that makes it easier to recover the function after we have lost it.

A simple example is the skill of riding a bicycle. We may not have done if for years, but we can pretty much get back on the bicycle and relearn it quickly. For strength training, it can take a little longer to recover to previous levels, but recovery is still at a faster rate than for people who are untrained.2

6. The Specificity Principle

Pavel Tsatsouline calls this principle “greasing the groove.”4 If we want to get better at something, we must do that something. If we want to get better at pull ups, do pull ups. Although leg presses might generalize to the squat, the squat itself will build greater squat strength.

This rule doesn’t indicate that we shouldn’t do ancillary exercises. For example, we might want to work grip strength outside of the deadlift to better hang onto the bar. However, we don’t want to do only ancillary lifts as the main exercise benefits our neurological system the best.

7. The General Adaption Syndrome

This principle might subsume the others as it contains three stages that overlap with other principles:

- The first stage is called the alarm stage, which is when the body reacts to the application of training stress (similar to the overload principle).

- The second stage is the resistance stage, which is when our muscles adapt to increasing amounts of stress (similar to the overcompensation principle).

- The final stage is the exhaustion stage, where if we continue to train we will be forced to stop from too much stress.

This syndrome has been revised and renamed the fitness-fatigue model. Much of the revised model is due to individual differences in how novice and elite athletes respond.1 Elite athletes fatigue differently and it takes a great deal more stressor to lead to the resistance stage (or overcompensation).

For novice athletes, exhaustion is easier to reach and thus, it might be best to have a wide range of activities to create fitness (to avoid exhaustion in one activity). It might be one reason for new athletes to gain greatly while beginning CrossFit. However, they need to change their training as they begin to respond differently.

Dr. Hatfield’s Perspective on CrossFit

Dr. Hatfield was a multifaceted athlete during college and after (participating in national-level events as a college gymnast (pictured above) and being a strong Olympic and power lifter). If CrossFit were around, he probably would have excelled. However, he had some concerns with the current CrossFit training methods:

I like everything about Cross Fit, but it’s not a system of training. By putting together all those different sports and activities … it doesn’t make any sense because what you do in one sphere is going to take away in another sphere. For example, you cannot become a great marathon runner and an Olympic weightlifter of note all at the same time.

It’s not going to work because the kind of training it takes to create great endurance removes from your ability to lift heavy weights, so you’re competing against yourself really by getting into Cross Fit. … I took the time to go over CrossFit’s methods with a backdrop of the Seven Granddaddy Laws to see what was going on. … they are breaking almost all the laws.

Take Home

In general these principles indicate that we can’t blindly follow programs. We all have different technical backgrounds, skeletal structures, and strength levels, to name a few differences. Our programming needs to be tailored to our goals and to us as individuals following the seven laws described above.

One common idea for a solution is to scale the weight in programs. However, that is only one method of trying to create an optimal program. We also need to consider the other laws in making the best possible program to fit our goals.

References:

1. Chiu, Loren ZF, and Barnes, Jacque. 2003. “The Fitness-Fatigue Model Revisited: Implications for Planning Short-and Long-Term Training.” Strength & Conditioning Journal 25 (6): 42–51.

2. Hortobágyi, T., L. Dempsey, D. Fraser, D. Zheng, G. Hamilton, J. Lambert, and L. Dohm. 2000. “Changes in Muscle Strength, Muscle Fibre Size and Myofibrillar Gene Expression after Immobilization and Retraining in Humans.” The Journal of Physiology 524 (1): 293–304. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00293.x.

3. Selye, Hans. 1950. “Stress and the General Adaptation Syndrome.” British Medical Journal 1 (4667): 1383.

4. Tsatsouline, Pavel. 2000. Power to the People!: Russian Strength Training Secrets for Every American. Dragon Door Publications.