As of late, I have been reading a lot about how CrossFit and rhabdomyolysis or “Uncle Rhabdo” are synonymous with one another, but the truth of the matter is, they aren’t. Rhabdo can happen in any sport. For example, when I was Thai boxing heavily, a friend of mine got rhabdo. Yes, from muay Thai boxing. Now, I am not a doctor, but I will write about rhabdo from a biological standpoint and how it affects the body. Then it will be up to you to make an informed decision on whether or not CrossFit is the only sport that causes rhabdo.

Rhabdomyolysis is essentially muscle breakdown and the release of intracellular contents. Injury to the myocyte membrane occurs, which can alter energy production. The underlying pathology involves direct damage to the sarcolemma or depletion of ATP within the myocyte that causes an unregulated increase in intracellular calcium concentrates and ends up initiating a destructive process. This un-regulation leads to constant contraction, energy depletion, and possible cell death.

Myocytes are muscle cells (biology lesson: myo = muscle, cyte = cell), but here we will specifically talk about skeletal myocytes. When the skeletal myocyte membrane becomes destroyed, the process of destruction begins with increased calcium in the blood. But myoglobin, which is a dark pigment that binds to oxygen and acts as a muscle reservoir for oxygen when the blood does not supply an adequate amount, has been identified as the primary muscle component contributing to the renal damage involved in rhabdo. This is the reason why people who have rhabdo will have a darkening of urine. It’s because of loss of myoglobin from the skeletal muscles.

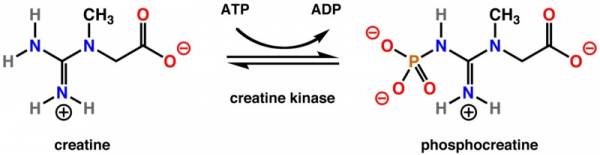

When diagnosing rhabdo, an elevated level of creatine kinase is usually a giveaway that a person has the pathology.Creatine kinase is the enzyme responsible for the reversible transfer of the terminal phosphate group of ATP to creatine to form phosphocreatine. A rise in creatine kinase means a rise in serum myoglobin (myoglobin in your bloodstream).

So, what does everything I just stated have to do with rhabdo? Well, all of these cellular reactions are supposed to be limited to the skeletal muscles. When your skeletal muscles break down during activity, these enzymes, waste, and protein molecules are released into the bloodstream and dealing with that puts a lot of pressure on the kidneys.

There are three mechanisms in which kidney injury can occur:

There are three mechanisms in which kidney injury can occur:

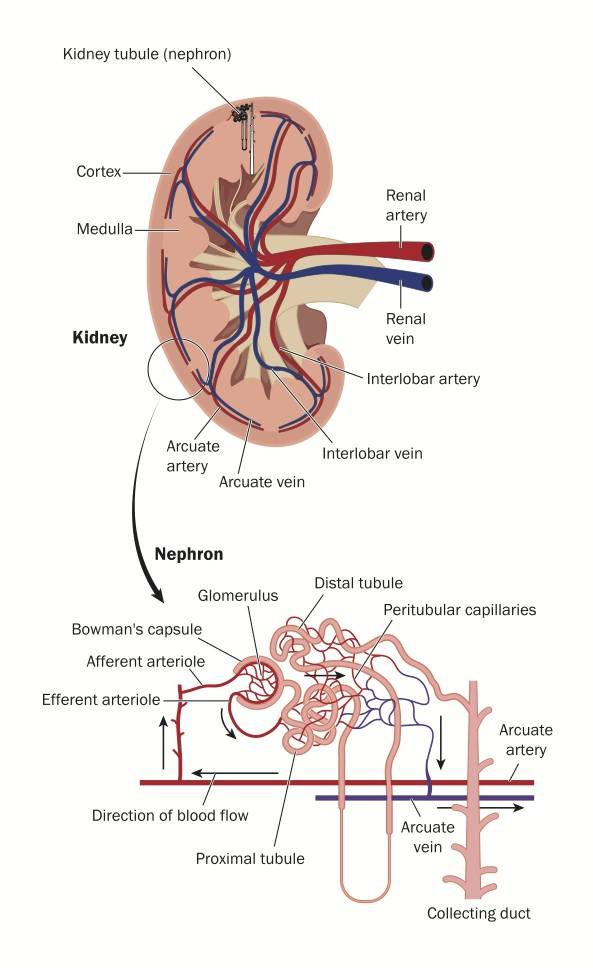

- The protein in myoglobin applies direct toxicity on the renal tubular cells.

- Myoglobin advances in the renal tubules and causes cast formations and tubular obstructions (basically plugs up the nephrons).

- Renal vasoconstriction is caused by platelets and endothelin. Endothelin are proteins that constrict blood vessels and raise blood pressure. If the perfect storm occurs, these factors can cause renal failure and death in severe cases.

Now before really freaking someone out, know that if caught in time, rhabdo is treatable, and in many cases the damage can be reversible.

So what the hell does all of this have to do with CrossFit? Honestly, not a damn thing. Every sport has the risk of rhabdo. Rhabdo is not specific to CrossFit because it can happen to anyone doing any activity. Those at risk include drug abusers, military recruits, athletes training above their level of conditioning, crush victims, athletes with predominance of type II fast twitch muscle fibers (i.e. sprinters and weightlifters), and type I slow twitch group (i.e. marathon runners). Also, don’t forget genetics. Just a few genetic factors impacting risk include adenosine deaminase deficiency, carnitine deficiency, and myoadenylate deaminase deficiency. So everything I just stated means anyone can get rhabdo.

Since the highest risk of rhabdo in CrossFit is when new athletes engage in the sport of fitness for the first time, the risk of it is fairly low. In most CrossFit gyms, many coaches make sure that new athletes scale all workouts until the coaches see the athlete is ready to move away from the progressions and increase rep schemes. The risk is there for elite athletes to get rhabdo, but in most cases it is fairly low, and the risk is highest in WODs like “Eva” and “Murph.” Those two WODs themselves are not workouts that are done everyday, and most CrossFit WOD durations are about twenty minutes long.

One thing to mention here, since most boxes are literally in a box (storage or industrial units), rhabdo can be exacerbated by hot, humid conditions; lack of heat acclimation; prolonged, profuse sweating; and not enough salt. So it’s important that those in humid, hot climates have fans available. I live in a warm area and every CrossFit gym I have been in has a fan.

I hate hearing people say that if you end up with rhabdo it’s your own fault, because it isn’t always. Sometimes it’s something that happens and it’s also important to mention that rhabdo can be asymptomatic in many cases. What does this mean? Sometimes you may not even know you are in the beginning stages of rhabdo. Only about 50% of rhabdo cases even have symptoms, and many times they mimic just basic muscle soreness.

I hate hearing people say that if you end up with rhabdo it’s your own fault, because it isn’t always. Sometimes it’s something that happens and it’s also important to mention that rhabdo can be asymptomatic in many cases. What does this mean? Sometimes you may not even know you are in the beginning stages of rhabdo. Only about 50% of rhabdo cases even have symptoms, and many times they mimic just basic muscle soreness.

If we want to curb cases of rhabdo, it’s important for coaches to continue doing what they have always done – scaling for new athletes, being vigilant for the elite athletes, and not being afraid to coach to your athletes even if it’s in the middle of a WOD because you notice certain symptoms. As long as CrossFitters as a community stay smart about rhabdo, maybe we can quell this strange couplet of CrossFit and rhabdo for good.

References:

1. Bagley WH, Yang H, and Stan KH. Intern Emergency Medicine: Rhabdomyolysis, U.S. National Library of Public Medicine.2013 Sep; 144(3):1058-65. Accessed September 20, 2013

2. Baechle, Thomas R., Earle, Roger W. (2008). Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. Nebraska. Human Kinetics

3. Tate, Philip. (2012). Seeley’s Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. New York. McGraw Hill Companies

4. Werner, Ruth. (2005). Guide to Pathologies. Maryland. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins

5. Adams, James G. (2013).Emergency Medicine: Clinical Essentials. Pennsylvania. Elsevier Saunders

Photos 3&4 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photos 1&2 public domain.