You do not sit in anterior pelvic tilt. It is a myth, it is wrong, and don’t make that mistake again.

“You have too much lordosis due to sitting in anterior pelvic tilt.” Actually, that’s BS.

You do not sit in anterior pelvic tilt. It is a myth, it is wrong, and don’t make that mistake again.

“You have too much lordosis due to sitting in anterior pelvic tilt.” Actually, that’s BS.

Sometimes a statement gets repeated so often that people take it as truth. It occurred when people assumed the world was flat, and that the pope was infallible. Up there with such unexamined stupidity is the mantra espoused by people who should know a hell of a lot better – “You have too much lordosis due to sitting in anterior pelvic tilt that causes you to have a tight psoas muscle.”

No! No! No! Three times no, I say! What is wrong with people? Having a hard time with reality? There are three things wrong with this statement.

First, the Research

A mountain of research demonstrates that the major cause of low back injury is as a consequence of lack of lumbar lordosis. Hence, the hate mail I received upon discussing flexed spine lifting, which was probably sent by people who don’t see their conflict in decrying lordosis in sitting and then complaining about spinal flexion in lifting.

Second, You Don’t Sit in Anterior Pelvic Tilt

Just look at the spinal posture of people in relaxed sitting around you, perhaps even as you are sitting now hunched over your computer (it’s posterior pelvic tilt, Beavis). Human beings, by and large, slump and are in posterior pelvic tilt when they sit.2,3

“[T]he concept that normal sitting posture occurs with increased lordosis is without medical and published evidence. It is in conflict with every respected paper and expert in this area.”

Then there was the beautiful study by Alexander, et al. in 2007, where upright MRI scans were performed and they showed the effect of functional positions on the movement of the nucleus pulposus. In sitting, there was significantly less lordosis than prone lying and standing, and significantly more posterior migration of the nucleus than other postures.

That’s right, medical studies, and I stopped counting after the first hundred. All of them agree that you sit in posterior pelvic tilt.

Third, Your Psoas Does Not Create Lordosis

The psoas is a hip flexor and spinal compressor, not a producer of lumbar lordosis. That’s right – the psoas, whether tight or not, does not create excessive lordosis. No, not ever. It’s wrong. Don’t say it. Zip It.5

Now, Put This All Together

Let’s observe the dominos as they fall. For many, this will be the first time the pieces have been put together for them.

So we agree that most low back disability is due to lumbar disc injury.6 This injury is as a consequence of migration of the nucleus posteriorly (due to posterior pelvic tilt and lumbar kyphosis in prolonged sitting and/or frequent/static lumbar flexion forces) and then a mechanical flexion force upon that nucleus is imposed. This flexion force, upon a posteriorly migrated nucleus, causes injury to the annular rings and/or posterior longitudinal ligament.

“A mountain of research demonstrates that the major cause of low back injury is as a consequence of lack of lumbar lordosis.”

Translated: You sit in a slump (posterior pelvic tilt) that causes the disc to have an increase in pressure upon the back area of the disc. You then bend over, the muscles do not hold the spine strongly for a moment, and this flexion force causes the disc to load more – it gets injured and a disc bulge is created.7

The disc bulge is at the back – not the front – of the disc.

What Do the Medical Studies Say?

When human beings sit in “normal” sitting posture (whether at work or at home), they sit with spinal flexion and posterior pelvic tilt.8, 9 Lumbar lordosis is an important protector against low back injury.2,11

That’s correct – lumbar lordosis is good for you, and because people sit in kyphosis, sitting is bad for you. So the concept that normal sitting posture occurs with increased lordosis is without medical and published evidence. It is in conflict with every respected paper and expert in this area. It is only espoused by individuals who do not have sufficient education or understanding of this area.

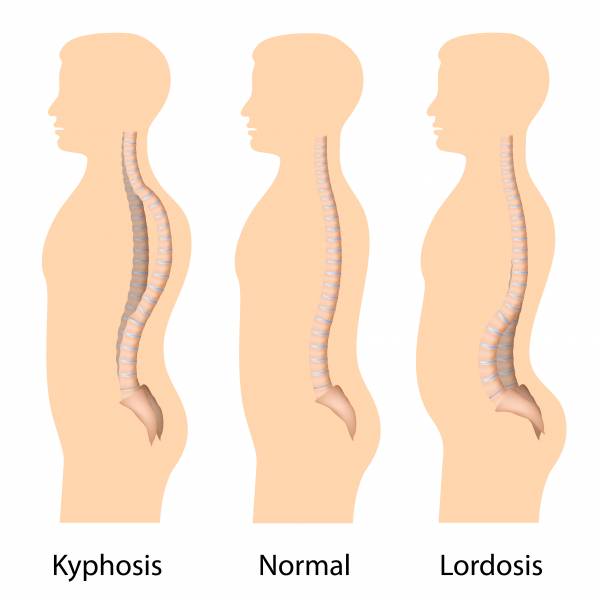

Just look at the x-ray graphics.

This posture, assumed since the dawn of thinking man, clearly has nothing to do with anterior pelvic tilt.

Yes, they are both posterior pelvic tilt and lumbar kyphosis.

Google any image search on poor posture in sitting. You are going to see a tsunami of slumped posture. How people espouse this “you sit with increased lordosis and anterior pelvic tilt” nonsense without seeing what they, and everyone else, do around them borders on mass delusion.

Where Did This Madness Begin?

In 2004, Eric Cressey and Mike Robertson published an article called Neanderthal No More. In it, they began with the premise that you:

…hunch over a computer all day. In other words, the only trait you share with this prehistoric badass is your pathetic S-shaped posture: rounded shoulders, forward head posture, exaggerated kyphosis, anterior pelvic tilt, excessive lordosis.”

Look, I understand they were a couple of young guys trying to make names for themselves in the industry, and mistakes can be made. A few years ago, I tried to contact one of the authors and offered to rewrite the errors, but never heard back from them. The article still exists and has not been corrected, so I figure the authors still stand by this work. It’s wrong in its premise, as I have proven, and requires revision. This is not disrespecting anyone. This is science and it’s about evidence.

Also, as a side note: Neanderthals were not our ancestors. We are Homo sapiens.

In Summary

- It is a fact most people sit in posterior pelvic tilt, not anterior (open your eyes, look around).

- It is a fact posterior pelvic tilt coincides with kyphosis, not lordosis.

- It is a fact the psoas does not cause lumbar lordosis (read McGill).

- It is a fact most disc injuries are causes by flexion forces.

- Lumbar lordosis prevents disc nucleus migration and protects lumbar spines.

“Human beings, by and large, slump and are in posterior pelvic tilt when they sit.”

I have used approximately 1,100 words in this article. I have used the most important 1,100 words necessary to complete this article. If there is anything you feel has been left out, then you may be correct, but what I have left out were words less important than the 1,100 I did use. It is not that there is not more I could have added, but there is a word limit and I’m stopping here. This article is not a discussion; it is scientific fact for you to understand.

Note: This article was written under a slowly spinning mirrorball at the bar of the Sunset and Lightning Club, made easier by Clase Azul Anejo tequila, Upmann cigars, and the “Atomic Riot” demo CD.

Further Reading:

- Rehabilitation for Lumbar Spine Recovery: The Science and the Truth

- Keep (Sumo) Deadlifting: Unorthodox Rehab for Lumbar Injuries

- Myths About Disc Bulges: They Are Not Forever – But Training Is

- New on Breaking Muscle Today

References:

1. L. Punnett, et al., “Back disorders and non-neutral trunk postures of automobile assembly workers,” Scandanavian Journal of Work Environment and Health, (1991) 17: 337-346

2. R. A. McKenzie, “Prophylaxis in recurrent low back pain,” NZ Med. J. (1979) 89; 22.

3. J.P. Callahan and S. M. McGill, “Low back loading and kinematics during standing and unsupported sitting,” Ergonomics, (2001b) 44(4): 373-381.

4. L.A. Alexander, et al., “The response of the nucleus pulposus of the lumbar intervertebral discs to functionally loaded positions,” Spine (2007) 32(14): 1508-1512

5. S. M. McGill, Low Back Disorders 2nd Ed., Human Kinetics, 2007.

6. S.D. Kuslich, et al., “The tissue origin of low back pain and sciatica: A report of pain response to tissue stimulation during operations on the lumbar spine using local anaesthesia,” Orthop Clinics of North America. (1991) 22:2;181-187

7. Fennell, et al., “Migration of the nucleus pulposus within the intervertebral disc during flexion and extension of the spine,” Spine (1996) 21: 23; 2753-2757.

8. B. Wyke, “Neurological aspects of low back pain,” In: The lumbar spine and back pain ed. M. Jayson. London, Sector Publishing (1976).

9. R.A. McKenzie, The Lumbar Spine: Mechanical Diagnosis & Therapy. Spinal Publications 1981

11. M.M. Williams, et al., “A comparison of the effects of two sitting postures on back and referred pain,” Spine (1991) 16:10; 1185-1191.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.