How does participation in college athletics affect body composition in women? There is surprisingly little research on the subject. On one hand, athletes and parents alike have heard horror stories of eating disorder-like behavior. On the other hand, coaches tend to credit their training programs with sometimes radical transformations.

In an attempt to determine what changes actually take place over an athlete’s college career, a study at the University of Texas at Austin collected pre- and post-season body composition measurements. The datea came from more than 200 female Division I athletes participating in one of five sports: basketball, volleyball, soccer, swimming, and track. Among track athletes, only sprinters and jumpers were considered, not distance runners or throwers. Measurements included height, total mass, lean mass, and body fat mass and percentage. Body composition measurements used DXA scan technology (also known as the DEXA scan), which is generally considered one of the most accurate available methods.

The athletes averaged 22.3% body fat at the beginning of their careers, notably less than the 31% body fat average for all freshman female non-athletes at the same school. However, the athletes reported about the same average BMI as their non-athletic peers. While BMI is often used as an easy-to-calculate stand-in for more accurate body composition metrics, these data make it clear that elevated BMI does not necessarily indicate excess body fat in athletes.

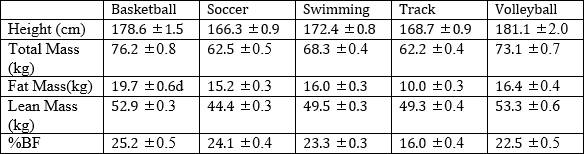

The table below summarizes the measurements. At this university, all five of the sports involved in this study were very competitive programs, regularly producing divisional and national championship-level teams. The authors hypothesized that the athletes had near-optimal body composition for their sports, and therefore differences between sports reflected divergent requirements. A preliminary comparison of volleyball and basketball players based on their positions supports this hypothesis. For example, basketball guards were shorter, lighter, and leaner than post players and volleyball defensive specialists and setters were shorter, lighter, and less lean than hitters and blockers.

Table: Means for body composition of various sports across multiple time points and years.

Observed = mean of all measures taken. Mean ±standard error

Some of the findings were unsurprising. For example, basketball players tend to be taller than other athletes. Others were less obvious. For example, the track athletes averaged just 16% body fat, which is notably less than the average for all athletes and near the bottom of the healthy range for women.

Very few changes were seen over the course of these women’s athletic careers. Within a single season, swimmers and track athletes lost fat mass and increased fat mass, but these changes did not persist over the longer term. Volleyball players added lean mass and kept it long-term, while basketball players added and kept both total mass and fat mass.

It’s not clear what conclusions, if any, can be drawn from this study. It is not, after all, surprising for athletes to have and maintain lower body fat than non-athletes. The data reflect changes in the athletic population as a whole, and therefore may not provide a good perspective on changes in individual athletes. There was also no attempt to correlate body composition with either training programs or power and strength measurements.

Finally, the potential for changes in the “typical” athlete over time, for instance as women’s collegiate sports become more competitive, makes comparisons across studies difficult. Overall, this study indicates possible directions for further research, but offers little guidance for athletes or coaches.

References

1. Philip R. Stanforth, et. al., “Body composition among female NCAA Division I athletes across the competitive season and over a multi-year time frame,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research., Published ahead of print, doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182a20f06

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.