In gym folklore not much surpasses the bench press. From Monday being International Bench and Curl Day to the constant “How much d’ya bench, bro?” question, the bench press is deeply rooted in our fitness psyche.

I feel like most people follow a three-stage journey in their pressing. The first starts with just loading as much weight as they can on the bar and doing whatever is needed to get that bar up. The second phase strikes when their shoulder begins to hurt and they start looking around for other alternatives. It’s at this stage where dumbbells and kettlebells tend to appear in training, as well as the possible migration away from lying pressing exercises to standing variations. The final stage is one that sees the virtual total elimination of all pressing exercises from people’s routines as they try to avoid surgery.

The biggest issue I see for many people in regards to pressing is that most – as in, two-thirds of people – aren’t actually built for it. You see, the AC joint comes in three different variations, not surprisingly called type I, type II, and type III, and it’s only type I that is actually set up to allow most people to press pain free. Those with types II and III have an issue in that they are likely to lose acromium space during pressing and put their rotator cuff at risk. The problem is that most people will only learn what types of acromium set up they have once they’ve actually hurt themselves and need an X-ray or MRI. Without X-ray vision there’s just no way to tell.

So what should the vast majority of people be doing if they want some pressing in their training? Firstly, ditch exercises that lock the hands into a single position. Yes, that means that barbell pressing, as well as handstand push ups, will be off the menu. That’s a small price to pay for not needing surgery.

The second step is to increase thoracic spine mobility. If you haven’t heard of the joint-by-joint approach let me give a summation here. The body flows from a joint that needs stability to a joint that needs mobility. If that gets messed up, then the entire system upstream is compromised.

- The foot – needs to be stable to deal with landing forces.

- The ankle – needs to be mobile and move in all directions.

- The knee – requires stability. (Imagine if your knee moved like your ankle? That’s called an ACL tear).

- The hip – like the ankle need to be able to move in all directions.

- Lumbar spine – needs to be stable

- Thoracic spine – needs to be mobile.

- Scapulae – stable.

- Shoulder – mobile.

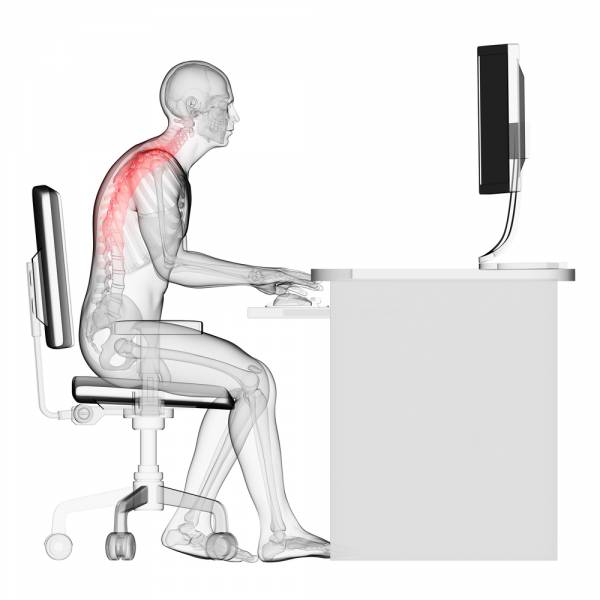

However, what usually happens is that we get things mixed up in our daily lives. Because we spend so much time sitting we turn our hips from mobile to stable. That means our lower back has to become more mobile to deal with the lack of movement from the hips. Because the lower back is hypermobile the thoracic spine stiffens up. And if the thoracic spine becomes immobile then the scapulae are forced to become mobile, then the shoulder itself becomes stiffer in an effort to take on some of the stability missing lower down.

However, what usually happens is that we get things mixed up in our daily lives. Because we spend so much time sitting we turn our hips from mobile to stable. That means our lower back has to become more mobile to deal with the lack of movement from the hips. Because the lower back is hypermobile the thoracic spine stiffens up. And if the thoracic spine becomes immobile then the scapulae are forced to become mobile, then the shoulder itself becomes stiffer in an effort to take on some of the stability missing lower down.

I’m not going to go into all the different methods of mobilizing the thoracic spine here, as there are plenty of great articles all over the Internet about that. But what if we came up with a different solution? One that still allowed us to put weight overhead?

I had a conversation with Primal Move creator Peter Lakatos quite a while ago regarding pressing versus snatching. Like me, Peter is middle aged and has a body that bears the marks of a life well lived, so I was wondering how he balanced pressing and snatching? He told me that he felt the shoulders had only so much ability to be used and if he focused on one then the other wasn’t used much. That concept fits quite well into the RKC training template, as it means if you press then you get your conditioning from swings.

More recently I had a conversation with Mark Reifkind, another battle-hardened iron warrior, and we were talking about how my shoulders were holding up during Ironman swim training with the addition of strength work. At that stage I was down to get ups and handstand holds (support and straight-arm strength versus bent-arm and press strength). But what I was finding was that the faster lifts didn’t put a strain on my shoulders. My exact words were, “Swimming plus pressing equals shoulder impingement, but swimming plus kettlebell ballistics are fine.”

The kettlebell ballistics usually are thought of as being swing and snatch, but really they should include push press and jerk as well. What Mark and I talked about was that these lifts bypass the AC joint and allow you to still train overhead movements, just not the press. The added benefit of these movements, when done with kettlebells (although you could use dumbbells for the same benefit) was that having two hands operating independently didn’t tie you into a single-hand position, freeing up some wiggle room in your shoulders. And if you’ve got really bad shoulders, then maybe a single kettlebell is an even better idea as the single overhead position allows even more wiggle room.

The kettlebell ballistics usually are thought of as being swing and snatch, but really they should include push press and jerk as well. What Mark and I talked about was that these lifts bypass the AC joint and allow you to still train overhead movements, just not the press. The added benefit of these movements, when done with kettlebells (although you could use dumbbells for the same benefit) was that having two hands operating independently didn’t tie you into a single-hand position, freeing up some wiggle room in your shoulders. And if you’ve got really bad shoulders, then maybe a single kettlebell is an even better idea as the single overhead position allows even more wiggle room.

That was when my ballistic shoulder complex was born. I decided that I liked all those movements equally and that if one was good, then all three combined must be better. The result is a simple three exercise complex, done with a single kettlebell – snatch, push press, jerk. The order is actually important because if you try to snatch last in that group you’re probably in for a big surprise, if you’ve used a decent-sized bell. My two favorite variations go like this:

Complex #1: 5-3-2 Increasing Weight

-

5 reps kettlebell snatch 24kg, then 5 reps push press 24kg, 5 reps jerk 24kg.

-

Switch hands and repeat.

-

3 reps snatch 28kg, then 3 reps push press 28kg, then 3 reps jerk 28kg.

-

Switch hands and repeat.

-

2 reps snatch 32kg, 2 reps push press 32kg, 2 reps jerk 32kg.

-

Switch hands and repeat.

Repeat this process for 2-3 total waves.

Complex #2: 1-2-3 Ladder

-

Perform 1 snatch, 1 push press, 1 jerk before switching hands and repeating.

-

Perform 2 snatches, 2 push presses, 2 jerks, before switching hands and repeating.

-

Perform 3 snatches, 3 push press, 3 jerks, before switching hands and repeating.

Repeat for 3-5 ladders. The difference here is that I would use the same weight for each rung of the ladder, with the focus on more time spent with a heavier bell.

These single bell ballistic complexes are great for those with shoulder problems who still want to do some upper body work while saving the fragile AC joint from either further damage or for other activities such as swimming. While there is a large chance that you will need to stop pressing at some point due to the shoulders you inherited from your parents, there is no need to stop overhead work all together.

Photo 1 courtesy of Shoulderdoc.co.uk.

Photos 2&3 courtesy of Shutterstock.