Despite being a highly practiced warm up and cool down method, static stretching has been under fire over the last few years. Virtually every scientific source has indicated it makes you weaker, both in the short and long term. However, two recent studies published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research had a different story to tell.

The Problem With Static Stretching

The problem with stretching is that it has a relaxing effect. Each muscle has a type of sensory receptor called a muscle spindle. The muscle spindle detects changes in the length of a muscle. Without these spindles, your joints and soft tissues would constantly be damaged by muscle activity. Instead, the muscle spindles activate the stretch reflex.

As a muscle lengthens, the spindles trigger the muscles to activate, and when successful this causes the motion to stop. It’s that muscle activation that creates the sensation of a muscle being stretched. What you are feeling when you stretch is the muscle activating to prevent further lengthening.

When you spend time static stretching, you are essentially practicing the skill of releasing this tension. Theoretically, the nervous system’s messages that tell the muscle to activate with powerful contraction will decline. As a result, any strength work done after stretching is done by relaxed muscles, which simply don’t express strength very well. This effect may last into the following day, so stretching on your off days might even be a bad idea.

Are Shorter Sessions Better?

It seems that shorter duration static stretching might not relax the muscles as much and have a reduced impact on strength. Both of the research teams in the Journal studies wanted to find out if it was true that shorter duration stretching was still fine for strength.

Both studies used various lengths of stretching plans followed by power maneuvers. Both groups of subjects also stretched muscles that were used specifically in the power exercises.

Results

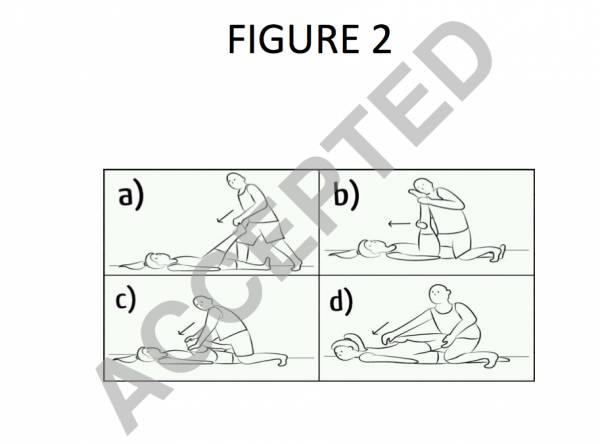

The first study compared the effects of thirty seconds of partner-assisted stretching to sixty seconds, measuring how each stretching program impacted a vertical leap test. Each subject performed the following four partner-assisted exercises (also pictured below):

- Straight-leg calf muscle stretch

- Supine straight-leg hamstrings stretch

- Supine hip flexion stretch

- Lying quadriceps stretch with hip extension

Pictured Above: Partner-assisted stretches performed in the first study

Stretching each muscle for sixty seconds did indeed reduce jumping by over three percent, compared to no stretching at all. Thirty seconds of stretching, however, had no significant effect.

In the second study, even more stretching lengths were compared, with intervals of ten, fifteen, twenty, thirty, forty, and sixty seconds. The subjects performed the following five stretches:

- Supine hip extensor stretch

- Butterfly stretch

- Side quadriceps stretch

- Semi-straddle stretch

- Standing calf stretch

The researchers wanted to see how the different stretch intervals affected ten- and twenty-meter sprints and a change of direction test. Speed improved after the two shortest stretching sessions, whereas the longer times had no effect. When the athletic ability of each athlete was compared, the researchers discovered this benefit was only present in the intermediate athletes, not the highly skilled athletes.

Both of these studies support the idea that stretching makes athletes weaker, but only if the stretching sessions are long enough to fully relax the muscles. Short static stretching is effective for flexibility, takes less time than longer stretching sessions, and may even improve power.

References:

1. Matheus Pinto, et. al., “Differential effects of 30-s vs. 60-s static muscle stretching on vertical jump performance Effects of volume stretching on jump performance,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000569

2. Alexandra Avloniti, et. al., “The Acute Effects of Static Stretching on Speed and Agility Performance Depend on Stretch Duration and Conditioning Level,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000568

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.