Many people are deficient at two fundamental skills essential to being a human – basic movement and breathing. This sounds hard to believe, but I assure you, it is true.

You may be suffering from the same fate and not even realize you have a problem. Let me explain.

Many people are deficient at two fundamental skills essential to being a human – basic movement and breathing. This sounds hard to believe, but I assure you, it is true.

You may be suffering from the same fate and not even realize you have a problem. Let me explain.

Regaining Lost Movement

Early in my career, I had the honor of working with individuals suffering from massive neurological impairments. Strokes, brain tumors, and a host of other medical maladies wreaked havoc on their brain’s ability to coordinate movement with the rest of the musculoskeletal system.

As a neurology-based therapist, one thing I always recognized when it came to working with these clients was the value of training primitive movements patterns like rolling, crawling, and balancing as precursors to “normal” human locomotion.

My clients spent endless hours training these natural movements to regain motor skill lost from neurological trauma. Inspiration was in no short supply as I watched them progressing through these patterns to regain their mobility and ability to interact with the world around them.

RELATED: 10 Scientifically Proven Ways Exercise Is Good for Your Brain

The Importance of Diaphragmatic Breathing

Impaired breathing and poor diaphragmatic excursion were also common findings in these clients. The diaphragm is fully integrated with the muscles of the abdomen and core through attachments to the ribs, sternum, lumbar spine, and hip (through the psoas)1.

Thus, efficient breathing requires coordination between the diaphragm and muscle of the trunk.

“But there are some common threads in my clients now. Many sit behind a desk all day and have racked up numerous injuries over the years.”

Through EMG studies, researchers have confirmed the diaphragm has a role in postural and core stability.2

Because large swaths of postural trunk muscles were often affected by neurological injuries in my clients, diaphragm function was also impacted. This happened whether the actual innervation to the diaphragm was damaged or not. Integrating diaphragm training was an essential component in the restoration of their movement.

RELATED:How to Breathe for Efficiency, Longevity, and Stress Relief

Applications to the General Client

Fast forward nearly two decades and most of my clients are still in a similar predicament. They lack the ability to perform efficient movement patterns and they suck at breathing.

Here is the rub, though – most of the clients I see now don’t have massive neurological impairments. They are considered healthy by all outside appearances. The same people you see at the gym, running marathons, or carrying on with their daily lives are the people I see.

They just have some nagging injury or performance deficit that doesn’t seem to improve.

“[W]hen we train proper movement for repetition and quality, we actually make proper movement more reflexive.”

But there are some common threads in my clients now. Many sit behind a desk all day and have racked up numerous minor injuries over the years.

Most of them exercise (some even work with professional trainers), but they still find themselves in a downward spiral of function and living in general.

These individuals have developed a level of strength, endurance, and performance over a base of poor movement and poor breathing.

The result is inefficient compensatory movement patterns that, while they may lack the severity of those I dealt with early in my career, are still devastating in their own right. These compensations usually go unnoticed for extended periods.

RELATED: Sitting at Your Desk Is Eating Your Muscles

The Science of Proprioception

The body moves inefficiently until there is some obvious and immutable evidence of damage.

By training motor skills through natural movement and efficient breathing, we can perhaps avoid these pitfalls. Research offers ample support for this idea. The type of training is important, though, and I believe MovNat has distinct advantages in this arena.

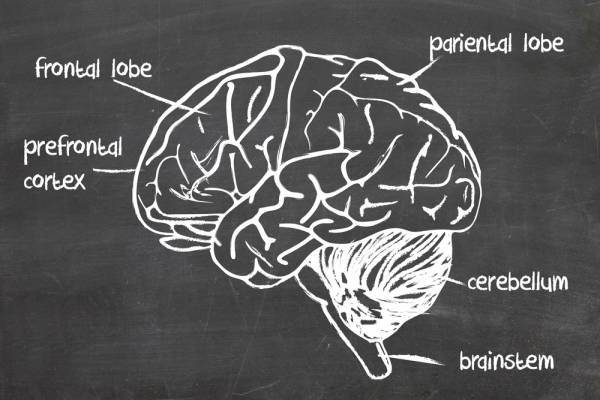

When researchers studied the brains of rats given unlimited access to a running wheel they found that thirty days of unlimited access did nothing to alter the development of motor maps within the motor cortex.3

Researchers also mapped the movement representation of the motor cortex of the brain when rats were trained for ten days on a skilled and more complex movement task. The motor cortex maps in this second scenario showed significant reorganization of movement representations.4

This type of remapping would be consistent with improved motor skill.

Scientific evidence has further demonstrated that when reflexive motor skill is developed it is encoded in the deeper regions of the brain (basal ganglia) that are responsible for automatic movements like eye function.4

So, when we train proper movement for repetition and quality, we actually make proper movement more reflexive.

Functional MRI studies have revealed the motor cortex of professional athletes demonstrates more focused activation patterns with imagery than untrained individuals.5

RELATED: A System for Maximizing the Movement Potential of Every Person

Legendary research based on proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) techniques for training is also rooted in the idea that the brain does not activate individual muscles – it coordinates movement.6

So by training primitive movement patterns and specific movement skills in a natural and developmental way, we are training motor skill in a way that develops our brain’s ability.

Improving Core Activation

Impaired activation of the “core” muscles has been demonstrated in studies involving those classified as failing movement screens (also known as poor movers).

Altered abdominal muscle activation as well as altered function of the diaphragm have also been demonstrated in those with low back pain.7

“[M]ost of my clients are still in a similar predicament. They lack the ability to perform efficient movement patterns and they suck at breathing.”

The diaphragm and deep abdominal muscles appose each other to maintain proper intra-abdominal pressure and support normal breathing. So normal function of both muscles should be required for efficient pain-free movement.

The take-home here is if you improve diaphragm function, you will indirectly influence intra-abdominal muscle activation. Taken together, these factors improve core stability and efficient pain-free movement.

Incorporate Basic Drills Into Your Routine

MovNat drills are the perfect addition to any program because training fundamental movement is the cornerstone of every aspect. The training mimics natural patterns of developmental movement acquisition for the motor system, as well as the diaphragm-core complex.

MovNat is a systematic path to better movement and functional ability as a human.

Start with some basic crawling and diaphragmatic breathing activities. Crawling is a fairly complex exploratory movement that requires the coordination of the left and right side of the brain, as well as reciprocal movement of the limbs.

Crawling also requires the ability to stabilize and mobilize joints in an extremely beneficial manner, and it is a significant building block for other movement skills.

Diaphragmatic breathing can be performed in a variety of ways, as well. Here are two great fundamental crawling exercises from MovNat and a great breathing exercise from the Postural Restoration Institute.

RELATED: Why MovNat Benefits Athletes in All Sports

Knee Hand Crawl

My biggest advice with this one is to be mindful of activating all of the muscles involved with the movement and to stabilize your core.

Foot Hand Crawl

This is a progression of the knee foot crawl. Both should be drilled for repetition and quality.

90/90 Breathing With a Balloon

This is perhaps my favorite breathing exercise of all time. Visit the Postural Restoration Institute for more details, but here are some general instructions and a video demonstration:

- Lie on your back with your hips and knees flexed to ninety degrees and your heels placed on the seat of a chair or box.

- Breathe in deeply through your nose while focusing on expanding your abdomen and rib cage laterally.

- Breathe out forcefully through your mouth, focusing on depressing your ribs inferiorly and expelling all of the air in your lungs.

- Following the end of the first exhalation, slightly posteriorly tilt your pelvis by driving your heels into the chair, lifting your butt about two inches off the ground.

- Hold the posterior tilted position for the remainder of the exercise and complete four more breath cycles. Following the fourth breath, relax, drop your hips, and repeat the drill one to two more times.

LEARN MORE: The Roots of MovNat With Coach Erwan Le Corre

The challenge is to train these movements for quality, endurance, repetition, and performance.

This series of exercises alone will make a difference in your general movement and athletic performance.

References:

1. Hodges PW, Richardson CA, Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain: a motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine. 1996;21:2640–50.

2. Kleim J, Cooper NR, Vandenberg PM, Exercise induces angiogenesis but does not alter movement representations within rat motor cortex. Brain Research. 2002: 934(1); 1-6.

3. Kleim JA, Barbey S, Nudo RJ, Functional reorganization of rat motor cortex following motor skill learning. Jour of Neurophysiology. 1998: 80(6); 3321-3325.

4. Wei G, Luo J, Sport expert’s motor imagery: Functional imaging of professional motor skills and simple motor skills. Brain Research. 2010:1341; 52-62.

5. Brown P, Roediger H, Mcdaniel MA, Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning. Cambridge. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 2014.

6. Voss DE, Ionta MK, Myers BJ, Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation: Patterns and Techniques. Philadelphia, Harper & Row Publishers, 1985.

7. Kolar P, Sulc J, Martin K, Sanda J Cakrt O, Andel R, Kumagal K, Kobesova A, Postural function of the diaphragm in persons with and without chronic low back pain. JOSPT. 2012; 42(4): 352-361.

Photos 1, 2 and 3 courtesy of Shutterstock.