Television race commentators frequently use the term “on form” to describe the race worthiness of a particular athlete. This week, I am exploring what it means to be on form and how to create a simple spreadsheet tool to help see if you are on form for your events and applying the right level of intensity to your training sessions.

The 2 Components of Being “On Form”

The first component is your level of fitness relevant to your particular sport. This is what you get from following a sustained training program. Over time, you will adapt and become stronger and have a greater cardiovascular capacity. The further you follow a sustained program, the more your overall level of fitness will rise, or at least will not decline. If you do not exercise for a while, you might expect your level of fitness to decrease slightly and the longer you do not exercise, or exercise very little, the further the potential decline.

The second component is how well you have recovered from your recent training sessions or your previous event. If you have been training hard or completed a long event during the last week, you might expect to feel a high level of fatigue. If your last training session or event was a week ago and you have been resting ever since, your level of fatigue will be low and some adaptation to the training stimulus will have taken place.

“The further you follow a sustained program, the more your overall level of fitness will rise, or at least will not decline.”

Taking the extreme positions as examples, if you have just completed a multiple-day block of hard training sessions, even though you have been training consistently for several months, you will still be fatigued and unlikely to be on form. Conversely, if you have been resting for a few months, your overall level of fitness might have declined and therefore you would not expect to be at your optimum for taking part in an event. The optimum position, where you are most likely to be on form, will be somewhere in the middle where you still have a high level of overall fitness (long term) and are not suffering from fatigue (short term).

Fitness Assessment

This overall concept is explained in some detail in the book Training and Racing with a Power Meter by Hunter Allen and Andrew Coggan, and there are some specific software tools available, as well. Several sports watch manufacturers provide internet-based analysis of your long-term fitness and recovery status and alternative third-party fitness software providers also allow you to plot your short- and long-term training activities.

“Assess overall level of fitness activity on a short- or long-term basis using a variety of custom metrics.”

All of these products can help you assess overall level of fitness activity on a short- or long-term basis using a variety of custom metrics. They will help show whether you are likely to have achieved that balance between long-term activity and lack of fatigue, and are therefore likely to be on form.

The Method for Measuring

But while these tools can have a significant level of detail and be backed up by various levels of research, if you do not have access to them, you can still create a simple scoring system using a spreadsheet.

First, you need to choose a measurement you can track on a regular basis. These might be estimates or measurements such as calories or steps from a fitness band or watch. You could also devise your own metric from the level of intensity (perhaps on a scale of one to ten) and duration of your session (in minutes). But you need to be consistent in the metric you use and recording all your sessions.

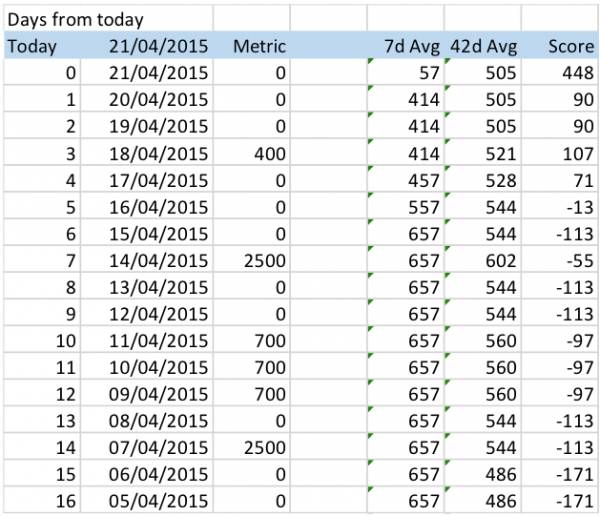

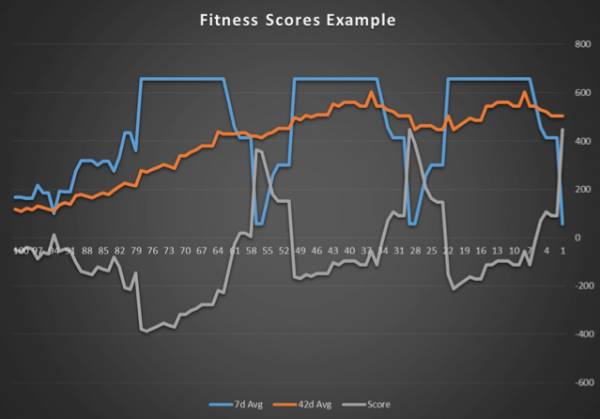

In this hypothetical example, I show an athlete who undertakes three shorter training sessions in the week and one longer session (such as a club ride) on the weekend. The metric has been chosen to indicate the larger training load at the weekends (2,500) compared to the weekdays (700). Every three weeks, the athlete has a recovery week to allow his body to adapt.

These numbers are all logged in a spreadsheet on a daily basis. Seven- and 42-day rolling averages are calculated (the same time constants as used by the Allen and Coggan model). I have used a simple average here rather than a more complex filter for illustration. These give an indication of the sustained effort over the short term (fatigue) and longer term (fitness), and the difference (score) is an indication of the level of “form.”

The chart below shows the variation in the three variables. As you might expect, the short-term (blue fatigue line) follows the level of activity and the fitness line (orange) shows a longer-term trend of slowly rising as more exercise takes place, dropping slightly in the weeks when little exercise takes place.

The recovery weeks show the fatigue line dropping and the score line rising. The peaks in the score line can therefore give an indication at a simple of level of when you are likely to be on form.

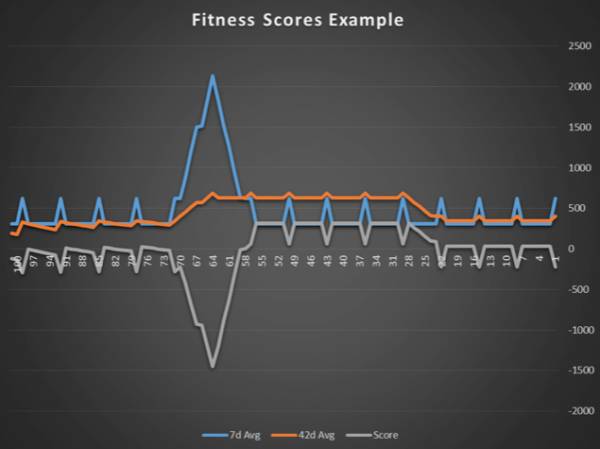

The second example shows an athlete who might undertake a single event once per week. In this illustration, her long-term average has reached a plateau and is sustained by the weekly event. At some point, she goes on a training camp, which is shown by a steep increase in the short-term (blue seven-day average) fatigue line.

This fatigue results in a drop in her overall score since she is tired. But due to the training effect, her long-term (42-day average) might rise. This benefit lasts for a just a few weeks, and the score line also rises, before the training effect is lost and she is back to her previous level of fitness.

Indication of Progress

While this model is simplistic and does not include the power-based intensity and duration metrics, heart rate variability, or more complex averaging calculations of some other models, it could be useful as a simple indicator of how you are progressing – and if you’re “on form.” If using the spreadsheet does not suit you, still consider trying out some of the tools that might come with a cycle computer or third party software.

More on fitness testing:

- Testing Training Methods: Are You Training Your Athletes Properly?

- A Simple Protocol For Testing Your Work Capacity

- Circuit Training Doesn’t Get You Fitter

- What’s New On Breaking Muscle Today

References:

1. Polar Personal Trainer, www.polarpersonaltrainer.com. Accessed April 21 2015.

2. Hunter Allen and Andrew Coggan, Training and Racing with a Power Meter, Chapter 8. VeloPress, Second Edition.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.

Charts courtesy of Simon Kidd.