Eddie Hall, “The Beast,” just deadlifted a savage 500kg, shattering his own record of 465kg from March of this year. This is one of the most impressive strength feats in recent history, a new benchmark for strength athletes to strive for.

Eddie Hall, “The Beast,” just deadlifted a savage 500kg, shattering his own record of 465kg from March of this year. This is one of the most impressive strength feats in recent history, a new benchmark for strength athletes to strive for. It’s also a great opportunity to examine the lifting mechanics of a titanic deadlift to see what you can apply to your own training.

The last few years have brought a new popular respect for individual differences in technique and programming based on limb lengths, anatomy, age, sex, and injury history. This is a vast improvement to the “insert-program-here” model of training, but these differences are often overblown. Eddie Hall’s deadlift may look like a whole different lift compared to yours, but on closer examination, it’s not so different after all:

Video from StrengthAsylum, used with permission. Lift begins at 1:22.

Squatting vs. Pulling

Some coaches will teach “experimenting” with hip position or tell their lifters: “the deadlift is a squat with the bar in your hands.” They’ll point to lifters like Ed Coan who appear to start their deadlift with incredibly low hips. But regardless of how you experiment with the start, the hips will go where they must in order to lift a 1RM weight. When a lifter starts with the hips artificially low, their hips will rise up first, often leading the coach to misdiagnose the issue and program mobility work or accessory exercises to correct a “weak link.”

This mistake comes from a superficial analysis of the lift. Many lifters appear to assume a squat position at some point in their setup – see Eddie at 1:24 of the video – but watch carefully what happens less than a second later, when the lift actually begins.

Left: Eddie Hall settling in with a prestretch before he begins pulling on the bar. | Right: Eddie’s position the instant the bar leaves the floor.

Eddie is certainly a special human being, but he’s not so special that he violates physics, and neither are you. In order to successfully a maximal-effort deadlift, you and Eddie will both end up hitting a few checkpoints at the exact moment you break the bar from the floor:

- The bar will be over your mid-foot. This will happen when the shins are angled just a little forward of vertical at the setup. You can see how far Eddie brings the knees back in order to start the lift. This does not mean you want ‘vertical’ shins. If the shins are perfectly vertical at the start, it’s a stiff-legged deadlift.

- The bar will be in physical contact with the leg. Eddie does this perfectly, and you can see the chalk flying as he drags the bar up into position.

- The shoulders will be forward of the bar. Eddie’s are only a hair forward because the load is so massive, but they don’t come to perfectly vertical until he’s near the finish. The arms can only be perfectly vertical at the start if the lats aren’t pulling, something that can only happens at submaximal weights or when the lifter is mentally ‘forcing’ the technique, leaving muscle mass out of the exercise and leaving pounds on the platform.

- The lower back will be held in normal, rigid extension. This is both for safety and because it’s incredibly difficult (sometimes impossible) to uncurl a bent lower back at the top of a maximal deadlift, and if the back won’t straighten, the lift doesn’t finish.

Notice that I didn’t say anything about how horizontal your back will be. Some coaches want to see a vertical back, but back position is the result of limb lengths, the checkpoints above, and a few things we’re about to discuss.

The Big Guy Bend

Rounding of the lower back should be avoided. Although it may not be “ideal,” upper back rounding is common and it’s important to know why in order to make an informed choice. Take a look at Eddie’s pull and imagine what would happen if he’d pulled with his back flat enough to satisfy a physical therapist. You can envision it here:

The blue line is what he did and the red line is the imaginary “perfect back.” Since he can’t change the length of his spine or the position of the bar, flattening his back would leave Eddie with one option: to raise his hips higher and lean further forward. This would require his back to do more work, and since his back is working as hard as it can just to keep him in one piece, that would likely mean a failed lift.

Konstantinovs, Hall, Coan, Bolton, and many other great deadllifters aren’t making a mistake by rounding. It’s almost an inevitability, and it is a calculated choice to start rounded and lock the spine in that position rather than risk disturbing the bar path mid-rep by curling under the load.

Should you do it? That depends. I don’t recommend this for my novice lifters and general strength trainees because I am using the deadlift, in part, to train the back, and fighting for a rigid, flat upper back serves that goal. However, a powerlifter/strongman in competition isn’t looking to get stronger ‘in general’ but in whatever way will lift the greatest weight, and for serious competitive lifters, it’s worth considering.

Caution: Wide Load

If you look closely, you’ll see that Eddie’s stance puts his shins about two inches into the knurling on either side. That’s a lot wider than most lightweights like myself. Other videos show it more clearly. Before we throw up our hands and say “play with your stance and figure it out,” let’s consider why his stance is so wide.

Your stance width affects your deadlift in two key ways:

First, the wider your stance, the more vertical your back gets. This is because the wider stance makes the femur (the thigh bone) shorter when viewed from the side. This is why the sumo stance makes for a more vertical back than the conventional.

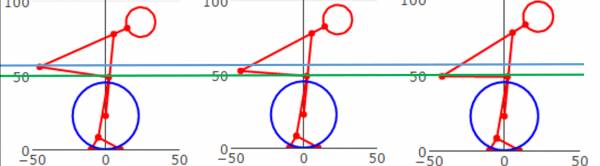

From the left to the right, we see the effect of a shorter and shorter femur. The blue and green lines highlight the height of the hips while the knee stays fixed. [Graphs provided by MySquatMechanics]

Second, it marks the limit of your hand position. In general, you want your arms to hang straight down to reduce the range of motion, allowing for a direct vertical pull on the bar, and bringing your hips closer to the bar. Thus, we come to a general rule of thumb for stance width that will be correct to within an inch or two: take the widest stance that will allow your knees to track with your toes while still keeping your arms straight up and down.

Eddie’s stance can be so much wider because comparing his shoulder width to mine is like comparing an 18-wheeler to a Prius.

On the left, yours truly lifting 235KG with shins 1-2 inches inside the knurling, compared to Eddie on the right.

On the left, yours truly lifting 235KG with shins 1-2 inches inside the knurling, compared to Eddie on the right.

The Big Picture

In the end, when you get past the superficial ‘look’ of it, Eddie Hall’s deadlift is very similar to yours and mine. When you put together the whippy bar (and the incredible load that’s bending it), wider stance, different limb lengths, and more-rounded back, Eddie’s starting position is a good bit more vertical than mine, but both are correct, and it would be incorrect for me to try to match Eddie’s stance width or back angle.

So what can you take away from this incredible performance?

Copying a champion’s “look” is like cheating off the answer sheet to a different test. If you ace the test, it’s only by dumb luck. Instead, learn the principles that make their lifts work, and apply those principles to yourself.

Trying to force a deadlift to look a certain way at lighter weights builds poor habits that have to be unlearned when lifting a maximal weight. If you want to concentrate on a muscle group, pick a different exercise, implement, or variant of the deadlift that better serves that purpose.

Humans come in all shapes and sizes, but we share the vast majority of our genetic code. While everyone’s lifts will look slightly different, even those at opposite ends of the spectrum begin to look similar when we learn the common threads that link them together.

Finally, with a basic understanding of classical mechanics, experience under the bar, and an Internet connection, you have direct access to the lifting mechanics of the world’s greatest lifters. You don’t need electrodes, a force plate, and a degree to tell you the difference between a trap bar deadlift and a conventional one. That fact alone may be more exciting than a 1102-pound deadlift. Maybe.

Want to move more weight right now? Try this: