Once in a while, technology appears to lap itself and develop much faster than we are able to make use of it. Athletes have witnessed a dazzling pace of technological innovation that has yet to be consolidated to become a meaningful, cohesive picture beyond the ability to measure and display data. Here’s what you should expect from the next generation of fitness technology.

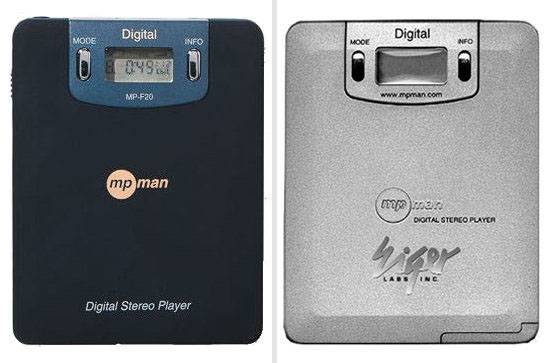

Back in 1997, SaeHan Information Systems (SIS) had a crazy idea. Its engineers imagined that we would abandon CD players, and store our music on a memory chip instead. The first commercially-available MP3 player, the SIS MPMan F10, had a capacity of 32 MB, barely enough to hold seven or eight songs. The sound that came out of it was flat, and for what it was able to do, it was insanely expensive.

Yet we all were fascinated by what the MPMan was able to do, even if couldn’t quite comprehend their use at the time; it was complex technology that needed someone who would be able to simplify it and understand the appeal to the mass market. The MPMan preceded Apple’s first iPod, the first device that made people really want a MP3 player, by about 3 years.

I can’t help but feel the same way when I am using fitness technology today. There are many products in the fitness tech market now that remind me of the MPMan. Let’s take Polar’s V650 bicycle computer as an example: The V650 is, more than two years after its initial release, still one of the most capable bicycling computers you can buy today. It’s also a showcase of what today’s fitness tech cannot do, as the leading fitness tech vendors (Polar, Garmin, and Fitbit) struggle with the opportunity to pioneer a huge new segment of the technology market.

A Fragmented, Siloed Industry

Finding the right technology to assist your individual training needs requires tons of research, and even then, you aren’t guaranteed to get what you’re looking for. Especially in the smartwatch segment, there is no single device that covers all functionality and conveniences an athlete may be looking for. The choice for or against a device often depends on the tradeoff you’re willing to make. Besides basic features, your consideration could include the software platform, interoperability with other devices and third-party applications, the ability to extend a feature set, upgradeability, and much more. Chances are, your purchase decision will end up a compromise.

Of course, the V650 isn’t a smartwatch, but it represents this conundrum very well. Polar got many things right with the V650, and given its peers in the market in 2014, the device was a stunning achievement. The V650 is visually gorgeous, and looks and feels much more expensive than its $300 price tag suggests. Even if it did nothing, I would keep it on my bike simply because of its sleek looks. Thanks to several software updates over its lifetime, Polar has extended its capabilities. Its fitness reporting remains very much in line with other high-end Polar devices, and tightly integrated with a chest strap heart rate monitor, which works beautifully.

The Polar V650 does very well as a cycling computer, but it’s not part of an overal user experience.

For those who focus on heart rate training, the V650 is about as good as it gets. However, if you’re looking for a device that is focused on performance training, I’ve found better choices, including clever smartphone apps that are available for the iPhone and Android phones.

So despite the updates, the V650 has its shortcomings—and they are representative of the industry as a whole. It suffers from a proprietary platform that, in today’s connected world, feels pretty limiting. There’s Bluetooth connectivity, but the software doesn’t allow connections to any more than just a few devices. There are user interface limitations, and there’s a very rough GPS navigation feature based on user-generated content via OpenStreetMap that just doesn’t cut it anymore.

Lots of Data, Little Actionable Advice

These limitations are just one part of what keeps devices such as the V650 from being considered “smart.” Besides the plain availability of data that is populated by countless devices and services, there’s also the challenge to help us understand this data. In the case of the V650, it can connect to Strava for social ride sharing, as well as TrainingPeaks for event prep via Polar’s “Flow” web service. As capable as these products are, the user will always end up with numbers and charts that may be impressive and pretty, but they’re complex and don’t “talk” to the user.

There are beginnings of interpretation of data, such as recovery status reporting. However, actionable advice is, despite a mountain of data, still scarce. Imagine: What if we used all that data in a more collaborative and cohesive way, not just to visualize our training in numbers, but to calculate meaningful results that help us better understand our physical abilities? What if your device could provide your health status updates in the same way Google reports traffic updates on your smartphone?

For this to happen would require today’s fitness technology to transform from being a data reporting tool, to a guide that interprets complex relationships of data sets, both those measured in real time and those calculated from measurements. Such an approach would enable simple, useful, and timely advice to end users in the same way services on our smartphones learn our habits over time, and inform us about traffic jams on our way to work—before we’re actually starting to drive.

Building an Ecosystem and Experience

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, he introduced a critical concept in how Apple would develop new products. Eventually, that concept saved the company from bankruptcy and laid the foundation for every new product from the iPod to the iPad.

Unlike a typical technology company, Jobs wasn’t excited about technology for its own sake. He zeroed in on the user experience, and considered technology simply a way to enable that experience. While product innovation often had focused on hardware and software capabilities and was defined by specifications, Apple began creating the experience first and then thought about the technology it would need to support the experience.

The MPMan was celebrated as a technology achievement in 1998, not an experience achievement. It was defined by its ability to store music, rather than an ability to enable a convenient way to acquire and consume music. In contrast, Jobs surrounded the iPod with an experience that was based on iTunes, as well as an interface and connectivity that enabled consumers to naturally interact with the iTunes platform.

The MPman was a device built for the sake of technology, not to enhance the buyer’s life.

Likewise, fitness tech vendors are behaving like the tech companies of the 1990s, focusing on technology first, and experience second. So far, they are largely ignoring the fact that the experience is the key to success. If we’re using Apple’s approach as the model; if we consider how Google has replicated the model as a successful variation, it doesn’t take much to see that there’s a door that is waiting to be opened by the fitness tech industry.

Consolidation is probably a necessary mechanism to make even more data available and build much more comprehensive and complete data sets. We’ve seen first acquisitions, such as Intel’s purchase of Recon, and that trend is likely to continue. However, the bigger opportunity lies in products that leverage the data to create “smart” services based on platforms that are not just open to third-party developers, but are actively nurtured by their owners.

What This Means for You

There is no fitness tracking product available today at any price point that can combine all the hardware and software features available today. Separate (and often incompatible) devices are required to access all the data that’s out there, from basic activity data such as speed and distance, to physical data such as heart rate, nutrition information, and oxygen and glucose levels, to neighboring data sets such as location and meteorological information.

The technology advancements that will signify the next generation in fitness technology won’t be simply new hardware and software. Integration and connectivity will become increasingly important in the near future, as it will allow us to use technology in very specific ways, tailored to individual needs, and without the need to make compromises.

Vendors such as Polar and Garmin have very specific advantages in this game to leverage their technology to create complete customer experiences. Figuring out how to combine the data that can be obtained via a multitude of hardware and software services into a single platform is still too complex for the average user. The true benefit of technology lies in the ability to connect and combine all data sets, interpret the information and provide actionable advice based on the user’s training progress and fitness status—far beyond the limited analysis reporting that is available today.

For us customers, it is an exciting time to witness an industry with quickly evolving products that enhance our ability to improve our health and help us become better athletes. Your next fitness tech devices will add more and more abilities of a sports and medical coach. As a natural progression, the software and hardware driving this trend will continue to evolve and support much more intuitive user interfaces.

This also means that we will be changing our criteria for how we will choose our next fitness device. In the not too distant future, we will be choosing a product not so much because of what it can do today. We will purchase a new device because of its ability integrate into the ecosystem of our existing devices, and leverage that data to create an intuitive, useful user experience that will bring us tangibly closer to our goals.

A step in toward the wearable tech future: