The Functional Movement Screen (FMS). As healthcare and/or fitness professionals and enthusiasts, we know the routine. We perform our seven movement pattern assessments. We score each movement pattern. We take note of any weaknesses, deficits, asymmetries, or limitations in flexibility. We design a rehab or fitness program consisting of what our patient or client can do safely to achieve his or her goals.

RELATED: Exposing The Importance of The Functional Movement Screen (FMS)

And, hopefully, our client’s condition improves. He or she moves more efficiently and safely or improves performance on the field or at work, and everyone happily moves on with their lives. Right? Isn’t this the way it is supposed to happen?

How Valuable Is the FMS?

But what if this cookie-cutter approach doesn’t work? What if your client completes the FMS without any significant weakness, deficits, asymmetries, or flexibility limitations, but is still limited functionally and having trouble performing at work or on the playing field? What then?

Do we abandon the FMS completely? Or does this potentially valuable evaluation tool still have merit in our treatment plan or fitness program?

I believe the FMS most certainly does have value, but based on a particular aspect of the screen. An aspect that, in my clinical experience, is frequently either never considered or not fully understood. I am talking about the aspect of neuromuscular control and sequencing.

When Measures Are Normal, But Movement Is Not

Let us use, for example, a female patient who comes to physical therapy with an order from her doctor for you to “evaluate and treat” generalized weakness. You decide to administer the FMS as part of your initial evaluation. Your patient performs the FMS without difficulty and scores twos throughout.

RELATED: Can the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) Actually Determine Ability?

According to the FMS, this particular patient has no outstanding deficits that would potentially limit her functionally. But despite three weeks of a treatment plan consisting of stretching and strengthening, your patient still cannot flex forward and touch her toes in sitting or standing position. She reports that this limitation is problematic in several aspects her life, including caring for her children and completing tasks at work.

So, being the thorough clinician that you are, you again tediously check all the normal parameters: hamstring and gastrocnemius flexibility, hip range of motion, lumbar flexion, pelvic tilt, and sacral angle. As with your initial evaluation, all the measures prove to be relatively normal. Without any new objective findings, you and your patient continue to blindly implement a program that is clearly ineffective.

Neuromuscular Control and Proper Sequencing

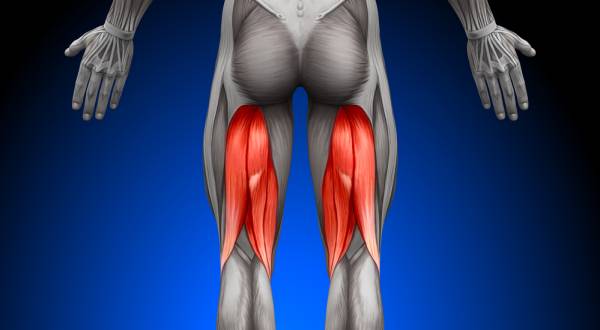

But the problem may not be the musculoskeletal system exclusively. Rather, this patient may have deficits related to neuromuscular control and proper sequencing of key functional movements. Consider that maybe this patient has an overactive posterior chain. In other words, her hamstrings and gastrocnemius-soleus complex are always on and she does not possess the ability to consciously turn them off.

As evident by your initial evaluation, it is not a posterior chain flexibility or tissue extensibility issue. Rather, it is a neuromuscular sequencing problem or motor control dysfunction. Gray Cook, one of the creators of the FMS, uses the term SMCD (stability or motor control dysfunction) to describe such a deficit.

But why does this happen? How do we develop muscle groups that are excessively active and hypertonic and limit normal functioning? In his book Movement, Cook provided a possible reason. He hypothesized that it is due to “pain, previous injury, or chronic dysfunction.” Furthermore, he stated that such dysfunctional patterns need to be broken before implementing an effective program to improve stability and motor control.

“Incorporating effective corrective exercise into a rehabilitation program requires thorough examination of a patient’s history and current condition as well as intense effort regarding design and implementation of stability and motor control corrections.”

Designing Powerful Corrective Exercises

Treatment of SMCD can be difficult and is, for the most part, outside the scope of this article. Evaluating and treating SMCD borders on application of the Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA). The SFMA is the clinical big brother to the FMS and is performed only by healthcare professionals (physical therapist, chiropractors, etc.). However, for discussion’s sake, we will consider how to approach SMCD.

Let’s be honest, the neuromuscular system is relatively abstract when compared to the musculoskeletal system. In our example, we can easily understand posterior kinetic chain tightness. We know the origin and insertion of the hamstrings, and we know several effective ways to stretch them, both at the proximal origin and distal attachment. Furthermore, we understand the gastrocnemius -soleus complex. And like the hamstrings, we can easily attack associated deficits in our treatment plan or fitness program.

But such superficial understanding of the musculoskeletal system is not sufficient to treat a true SMCD. As Cook stated in Movement, “[W]e cannot simply lengthen a tight muscle or move a stiff joint and think we have effectively changed a movement pattern.” Unlike the musculoskeletal system, the neuromuscular system is not always so easily understood. As a result, it is often ignored. Incorporating effective corrective exercise into a rehabilitation program requires thorough examination of a patient’s history and current condition as well as intense effort regarding design and implementation of stability and motor control corrections.

Two Important Factors in Designing Corrective Exercises

True corrective exercises are not challenges to the body. Rather, they are challenges to the brain. Gray Cook went as far describing corrective exercises as “experiences” instead of exercises. It is important to remember the brain has developed and memorized faulty and inefficient movement patterns that inevitably lead to dysfunction and injury. The brain and body would love nothing more than to continue to perform and refine these patterns as long as possible (as long as we allow).

In order for corrective exercise to be effective, the brain must perceive that it cannot perform a new challenge (or experience) without developing a new behavior. The brain realizes the previously learned, faulty movement patterns are not sufficient to support the new demand and a new behavior must be learned.

Corrective exercises must also remove all compensatory strategies and techniques. The brain is a master at creating and using compensation patterns throughout life, particularly when faced with injury or pain. This talent can be a wonderful thing, but it becomes problematic when compensatory techniques are developed with no regard for quality.

“In order for corrective exercise to be effective, the brain must perceive that it cannot perform a new challenge (or experience) without developing a new behavior”

Habits are formed for the sole purpose of immediate survival (or function). The brain never considers potential detriment, injury, or dysfunction in the future. It is not until these detriments, injuries, or dysfunctions present (possibly years in the future) that we become motivated to correct them. So, it is imperative that corrective exercises remove compensatory patterns and force the brain to adopt a new, safer solution.

Conclusion

Treatment of SMCD is not always the answer. Often, your patient or client may truly only be lacking hamstring flexibility or shoulder range of motion. But if your current plan is ineffective in addressing whatever deficits exist, consideration of neuromuscular control and sequencing may prove to be invaluable.

References:

1. Cook, G. Movement: Functional Movement Systems (Santa Cruz, California, 2010).

Photos 1 & 3 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 courtesy of Jorge Huerta Photography.