That may sound like utter nonsense. After all, strength literally means your muscles’ ability to generate force as they contract and expand. So how could anything be more important than your muscles when it comes to developing strength?

Source: Bev Childress

That may sound like utter nonsense. After all, strength literally means your muscles’ ability to generate force as they contract and expand. So how could anything be more important than your muscles when it comes to developing strength?

Source: Bev Childress

According to a study from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the nervous system may be as important as your muscles. As the data suggests, neural adaptation to heavier weightlifting can cause greater strength gains than low-load lifting.

The study examined what happened when 26 men trained with either high (80% 1-Rep Max) and low (30% 1-Rep Max) weight. Three times a week, the participants all trained until muscle failure, and the training continued for six weeks.

In addition to the training, the researchers also connected participants muscles to an electrical current that stimulated the nerves. This was done to measure voluntary activation: the amount of muscle activation generated through voluntary muscle contractions.

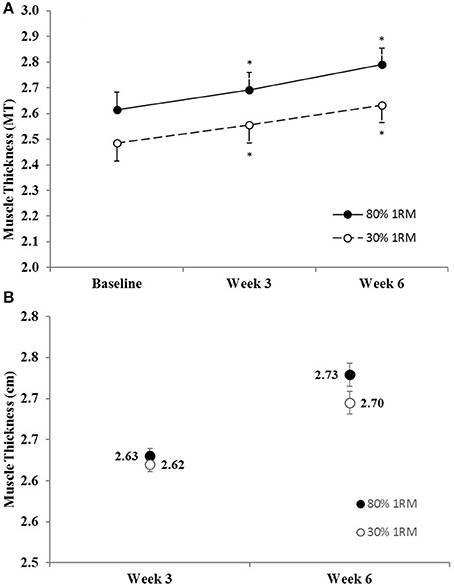

(A) Muscle thickness in the 80 and 30% 1RM groups at Baseline, Week 3, and Week 6; and (B) adjusted means for muscle thickness in the 80 and 30% 1RM groups at Week 3 and Week 6. Error bars are standard errors. *Indicates a significant increase from Baseline.

After just three weeks of regular weight training, the control group (low weight) saw a small increase in voluntary muscle activation, just 0.15%. However, the experimental group (high weight) saw a significantly larger increase, as much as 2.35%. That’s a huge difference between the two groups.

What does this increase mean? It doesn’t seem like a whole lot of weight, just a 2.35% increase (from 100 pounds squat to 102.35 pounds). Well, it’s not about the weight—it’s about the voluntary muscle activation.

This increase in electrical activity in the muscles led to a higher activation of motor units in the muscle during maximal contraction. By increasing motor unit activation, the heavier training led to higher overall strength.

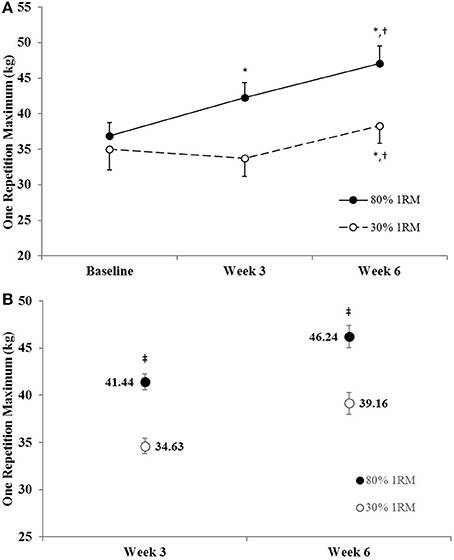

(A) One repetition maximum strength in the 80 and 30% 1RM groups at Baseline, Week 3, and Week 6; and (B) adjusted means for one repetition maximum strength in the 80 and 30% 1RM groups at Week 3 and Week 6. Error bars are standard errors. *Indicates a significant increase from Baseline. †Indicates a significant increase from Week 3. ‡Indicates a significant difference between the 80 and 30% 1RM groups. 80% 1RM > 30% 1RM.

But there was another benefit: in low-weight conditions, voluntary muscle activation decreased. As one researcher said, “If we see a decrease in voluntary activation at these sub-maximal force levels, that suggests that these guys are more efficient.

They are able to produce the same force, but they activate fewer motor units to do it.” The fewer motor units that are engaged, the less energy is used, and the slower the muscles become fatigued.

Think of it like lifting a soup can: a baby has to use all their strength so they would tire quickly. An adult only uses some of their strength so they can lift cans all day long.

Yes, your muscles are the prime movers in your overall strength. However, they’re not the only players in town. By increasing voluntary activation in heavy-load situations, you enable your muscles to handle more weight with less risk of fatigue. That’s the real reason heavy weight training yields better long term results than low-weight training.

“If you’re trying to increase strength – whether you’re Joe Shmoe, a weekend warrior, a gym rat or an athlete – training with high loads is going to result in greater strength adaptations,” said Nathaniel Jenkins, an assistant professor of exercise physiology at Oklahoma State University who conducted the research for his dissertation at Nebraska.

Reference:

1. Nathaniel D. M. Jenkins, Amelia A. Miramonti, Ethan C. Hill, Cory M. Smith, Kristen C. Cochrane-Snyman, Terry J. Housh, Joel T. Cramer. “Greater Neural Adaptations following High- vs. Low-Load Resistance Training.” Frontiers in Physiology, 2017; 8 DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00331.