EDITOR’S NOTE: While we normally interview our featured coaches, that was not possible with Paul Wade. In fact, Paul Wade does not do interviews and does not allow photographs of himself. Why? Because the “convict” in Convict Conditioning is no joke.

The following in an excerpt from Coach Wade’s book Convict Conditioning:

How I Learned My Craft: Doing Time

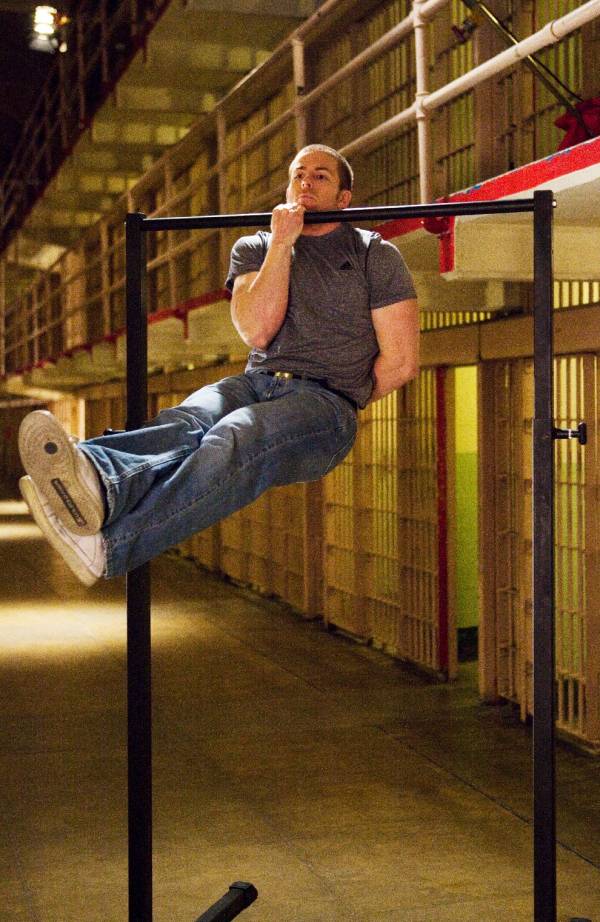

Luckily, the hidden system of old school calisthenics has survived. But it was only able to survive in those dark places where men need maximum strength and power just to stay alive; places where, for prolonged periods, barbells, dumbbells and other forms of modern training equipment may not be available, if ever. Those places are called penitentiaries, jails, correctional institutes and all the other names civilized men give to the cages where they keep less civilized men safely behind bars.

My name is Paul Wade, and sadly I know all about life behind bars. I entered San Quentin State Prison for my first offense in 1979, and went on to spend nineteen of the following twenty-three years inside some of the toughest prisons in America, including Angola Penitentiary (a.k.a. “The Farm”) and Marion – the hellhole they built to replace Alcatraz.

I also know about old school calisthenics; maybe more than anybody else alive. During my last stretch inside, I became known by the nickname Entrenador, which is a Spanish word for “coach,” because all the greenhorns and new fish came to me for my knowledge on how to get incredibly powerful in super-fast time. I garnered a helluva lot of favors and benefits that way, and I earned it, too – my techniques work. I myself got to a level where I could do more than a dozen one-arm handstand pushups without support – a feat I have never seen replicated, even by Olympic gymnasts. I won the annual Angola pushup/pullup championship held by the inmates for six years in a row, even though I was subject to full daily shifts of manual labor in the working farm. (This was a technique used in the Pen to reduce trouble – inmates put to work on the farm were generally too exhausted by the end of the day to mess with the guards.) I even came third in the 1987 Californian Institutional powerlifting championship – despite the fact that I have never trained with weights. (I only entered on a bet.) For more years than I care to count, my training system has kept me physically tougher and head-and-shoulders stronger than the vast majority of psychos, veteranos and other vicious nutjobs with whom I’ve been forced to rub shoulders for two decades. And most of these guys worked out – hard. You might not read about their training methods or accomplishments in fitness magazines, but some of the world’s most impressive athletes are convicts.

Throughout my time in prison, getting and staying as strong, fit and overall tough as possible has been my trade. But I didn’t learn that trade in a comfortable chrome-covered gym, surrounded by tanned posers and spandex vixens. I didn’t qualify as the result of a three-week correspondence course, like most of the personal trainers around today. And I sure as hell ain’t some fatass writer who never sweated a day in his life, like a lot of the guys who churn out “fitness” or “bodybuilding” books. Nor was I born a “natural athlete.” When I first wound up in the joint – only three weeks after my twenty-second birthday – I weighed a hundred and fifty pounds soaking wet. At 6’1 my long, gangly arms looked like pipe cleaners and were about half as strong. Following some nasty experiences early on, I learned pretty quickly that other prisoners exploit weaknesses like they breathe air; intimidation is the daily currency in the holes I’ve wound up in. And as I wasn’t planning on being anyone’s bitch, I realized that the safest way to stop being a target was to build myself up, fast.

Throughout my time in prison, getting and staying as strong, fit and overall tough as possible has been my trade. But I didn’t learn that trade in a comfortable chrome-covered gym, surrounded by tanned posers and spandex vixens. I didn’t qualify as the result of a three-week correspondence course, like most of the personal trainers around today. And I sure as hell ain’t some fatass writer who never sweated a day in his life, like a lot of the guys who churn out “fitness” or “bodybuilding” books. Nor was I born a “natural athlete.” When I first wound up in the joint – only three weeks after my twenty-second birthday – I weighed a hundred and fifty pounds soaking wet. At 6’1 my long, gangly arms looked like pipe cleaners and were about half as strong. Following some nasty experiences early on, I learned pretty quickly that other prisoners exploit weaknesses like they breathe air; intimidation is the daily currency in the holes I’ve wound up in. And as I wasn’t planning on being anyone’s bitch, I realized that the safest way to stop being a target was to build myself up, fast.

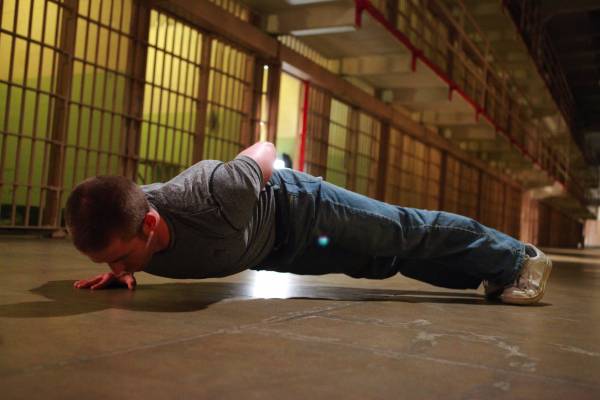

Luckily after a few weeks in San Quentin, I was placed in a cell with an ex-Navy SEAL. He was in great shape from his military training, and taught me how to do the basic calisthenics exercises; pushups, pullups, deep knee-bends. I learned good form early on, and training with him over the months put some size on me. Working out in the cell every day gave me great stamina, and soon I was able to do hundreds of reps in some exercises. I still wanted to get bigger and stronger however, and did all the research I could to learn how to get where I wanted to be. I learned from everyone I could find – and you’d be surprised at the cross-section of people who wind up in the joint. Gymnasts, soldiers, Olympic weightlifters, martial artists, yoga guys, wrestlers; even a couple of doctors.

At the time I did not have access to a gym – I trained alone in my cell, with nothing. So I had to find ways of making my own body my gymnasium. Training became my therapy, my obsession. In six months I had gained a ton of size and power, and within a year I was one of the most physically capable guys in the hole. This was entirely thanks to old school, traditional calisthenics. These forms of exercise are all but dead on the outside, but in the prisons knowledge of them has been passed on in pockets, from generation to generation. This knowledge only survived in the prison environment because there are very few alternative training options to distract people most of the time. No pilates classes, no aerobics. Everybody on the outside now talks about prison gyms, but trust me, these are a relatively new import and where they do exist they’re poorly equipped.

One of my mentors was a lifer called Joe Hartigen. Joe was seventy-one years old when I got to know him, and was spending his fourth decade in prison. Despite his age and numerous injuries, Joe still trained in his cell every morning. And he was strong as hell, too; I’ve seen him do weighted pullups using only his two index fingers for hooks, and one-arm pushups using only one thumb were a regular party trick of his. In fact he made them look easy. Joe knew more about real training than most “experts” will ever know. He was built in the old gyms in the first half of the twentieth century, before most people had even heard of adjustable barbells. Those guys relied largely on bodyweight movements – techniques that, today, we would regard as part of gymnastics, not bodybuilding or strength training. When they did lift “weights,” they didn’t lift seated on comfortable, adjustable machines; these guys lugged around huge, uneven objects like weighted barrels, anvils, sandbags and other human beings. Lifting like this calls into play qualities that are important for power, qualities that are missing in modern gyms – things like grip stamina, tendon strength, speed, balance, coordination and inhuman grit and discipline.

One of my mentors was a lifer called Joe Hartigen. Joe was seventy-one years old when I got to know him, and was spending his fourth decade in prison. Despite his age and numerous injuries, Joe still trained in his cell every morning. And he was strong as hell, too; I’ve seen him do weighted pullups using only his two index fingers for hooks, and one-arm pushups using only one thumb were a regular party trick of his. In fact he made them look easy. Joe knew more about real training than most “experts” will ever know. He was built in the old gyms in the first half of the twentieth century, before most people had even heard of adjustable barbells. Those guys relied largely on bodyweight movements – techniques that, today, we would regard as part of gymnastics, not bodybuilding or strength training. When they did lift “weights,” they didn’t lift seated on comfortable, adjustable machines; these guys lugged around huge, uneven objects like weighted barrels, anvils, sandbags and other human beings. Lifting like this calls into play qualities that are important for power, qualities that are missing in modern gyms – things like grip stamina, tendon strength, speed, balance, coordination and inhuman grit and discipline.

Read other excerpts from Paul’s books:

The Forgotten Art of Bodyweight Training

Old School vs. New School Calisthenics

To follow Coach Wade’s three weeks of workouts here on Breaking Muscle follow this link:

Strength & Conditioning Workouts from Paul Wade

Convict Conditioning and Convict Conditioning 2 are available through Dragon Door.