Powerful Facts About Peak Power Training

- Peak power outputs are correlated with increased jump height, running speed, and enhanced weightlifting outcomes

- Increased power outputs can enhance all barbell lifts (squats, deadlifts, bench press, and the Olympic lifts)

- Increasing your power production will enhance fast twitch muscle mass, fat loss, and caloric expenditure

- Peak power training principles are important not only for formal athletes, but military, first responders, and aging populations

The Science

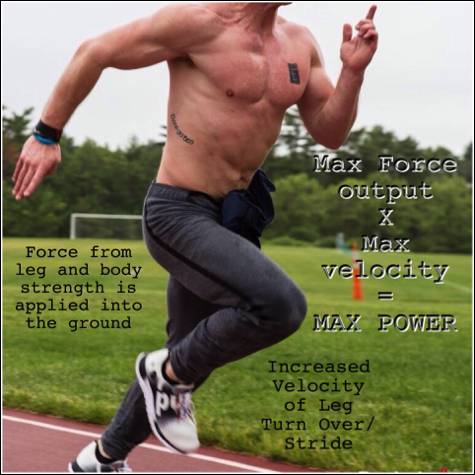

The ability to exert peak power outputs is a balance between high amounts of force output and velocity. Finding the sweet spot between those inversely related variables will result in a great potential for muscle gain and performance.

Power training specifically targets fast-twitch muscle fibers. Those same muscle fibers are recruited first in all human movements, but the trainability of those fiber types is extremely specific to peak power training. Additionally, fast twitch muscle fibers are responsible for muscular tone, which is the rate at which the muscle fibers individually fire. The more “excited” a muscle fiber is, the more power it will produce and the greater tone it will have.

Power training can result in increased fast twitch muscle mass, improved strength capacity (you just gained new muscle that is predominantly built through power training), increased muscle firing rates, and greater resting metabolic rates.

“Many athletic endeavors rely heavily on the force-velocity relationship, i.e. power production, which is the product of maximal force over a given amount of time.”

The specificity of this type of training has a profound effect on:

- Type II muscle fiber count (fast twitch)

- Increased muscle fiber size

- Increased muscle fiber firing rate

- Increased central nervous system activity

- Potentially increased resting metabolic activity (i.e. caloric expenditures), leading to positive correlations with lower body compositions

Many athletic endeavors rely heavily on the force-velocity relationship, i.e. power production, which is the product of maximal force over a given amount of time. The more force someone can apply at the highest velocity, the better his or her peak power outputs. And that is a key performance indicator in formal athletics that involve short intense bouts of activity, like martial arts, military training, powerlifting, and Olympic weightlifting.

Athletes

The easiest way to explain the above formula is to envision a running back, a defensive lineman, and a linebacker. Let’s assume a running back is traveling at the same speed (12mph) and direction in both scenarios.

- In Scenario A, the 300lb defensive lineman collides with the 200lb running back at 8mph. The power product of that collision is 4,800 (300*8 + 200*12).

- In Scenario B, you have the same running back at the same speed colliding with a 240lb linebacker traveling at 12mph in the open field, with a power product of 5,280 (240*12 + 200*12).

Both collisions were powerful, yet the linebacker was a more efficient power producer with a better ratio of force output and velocity for his given positional responsibilities. Therefore, most athletic teams train for peak power with the realization that a stronger, faster, and more powerful athlete will have enhanced opportunities for success

Military and First Responders

When real-life chaos is bearing down on the select few who protect and serve our country, rights, and way of life, peak power is critical to performing those responsibilities and saving lives. Hand-to-hand combat, jumping, sprinting out of harm’s way, running stairs with 100+lbs of gear on to save you from a burning building, and running down a junkie after an attempted arrest are just a few scenarios in which fast-twitch muscle fibers are predominantly recruited.

The ability to be forceful and to exert that force at high velocities will help save lives.

The Aging Population

Research suggests that between the ages of fifty to seventy, there is an average loss of 30% muscle and strength. Furthermore, the degree of fast-twitch muscle loss is far greater than slower twitch fibers. The loss of the ability to move quickly with stability and confidence results in falls, broken bones, and hospitalization – the trifecta for pneumonia and fatal health complications over time.

Am I saying to throw your grandmother on a weightlifting platform? No, but I do feel that basic central nervous system and explosive training principles can and should be adapted to aging populations to improve quality of life.

Strength and Conditioning Applications

Research has suggested that the optimal loading percentage for upper-body peak power training is about 42% of your bench press max. When you are able to increase power outputs on sub-max loads, the athletic payoff in contact sports, plyometric exercises, and even increasing your bench press strength is positively affected.

Additionally, peak power outputs for lower body training have been shown to be about 10-20% of your squat RM. Westside Barbell’s Louie Simmons has found 40-60% of 1RMs to be effective when using dynamic barbell training, with more advanced athletes actually having greater power outputs using lighter loads (increased firing synchronization and rate). The takeaway here is that performing loaded barbell or dumbbell jump squats can improve your ability to sprint faster, run harder, jump higher, squat heavier, and produce more power.

The Peak Power Plan

This is a stand-alone plan. I highly recommend you adhere to its intensities and systematic approach to achieve maximal results, and that you minimize any other additional strength and power programming.

“Over time your loads should increase and your bar speeds should remain constant.”

If you are not able to fully commit to this program due to other programming requirements (from your coaches or if you’re currently in the middle of a program), then I recommend you experiment with inserting one day per week into your current program. For example, pick day one to do during the first week of the month, day three the second week of the month, and day two in the third week of the month, leaving the fourth week free to recuperate from the intense monthly training cycle.

If you are in between programs or eager to start, and your goals are similar to the outcomes of this program, then I recommend you do all three days as your sole strength-training program.

Day 1

A1. Hang Power Clean 5-8 sets of 2 reps

B1. Back Squat 5 sets of 6-8 reps

B2. Dumbbell Bench Press 5 sets of 8-12 reps

C1. Barbell Deadlift 5 sets of 6-8 reps

C2. Weighted Pull Up 5 sets of 8-12 reps

Day 2

A1. Hang Power Snatch 5-8 sets of 2 reps

B1. Bent Over Row 5 sets of 6-8 reps

B2. Weighted Dips 5 sets of 8-12 reps

C1. Jump Squat 3-5 sets of 3-5 reps

C2. Kettlebell Swing 5 sets of 8-12 reps

Day 3

A1. Push Press/Push Jerk 5-8 sets of 2 reps

B1. Dynamic Deadlift 5-8 sets of 1-2 reps

C1. Dynamic Bench Press 6-10 sets of 1-3 reps

D1. Dynamic Squat 5-8 sets of 2-3 reps

E1. Barbell Curl 5×8-12

E2. Skullcrusher 5×8-12

More Details on the Plan

Olympic Lifts (Cleans, Snatches, Jerks)

Sets x Reps: 5-8 x 2

Load: 70-85% of RM

Bar Velocity: Record your sets and compare each week before increasing load

Dynamic Bench Press

Sets x Reps: 6-10 x 1-3

Load: 30-40% of RM

Bar Velocity: Record your sets and compare each week before increasing load

Jump Squat

Sets x Reps: 3-5 x 3-5

Load: 10-20% of RM

Bar Velocity: Record your sets and compare each week before increasing load

Dynamic Squat

Sets x Reps: 5-8 x 2-3

Load: 40-60% of RM

Bar Velocity: Record your sets and compare each week before increasing load

Dynamic Deadlift

Sets x Reps: 5-8 x 1-2

Load: 40-60% of RM

Bar Velocity: Record your sets and compare each week before increasing load

How to Progress the Plan

In the beginning your body will need to learn to move at optimal speeds. Once you have matched your previous bar speed with the same loads on two different sessions, increase the load by 2-5% and develop optimal speed at that load. Over time your loads should increase and your bar speeds should remain constant.

Check out these related articles:

- More Power, Faster: Benefits and Limits of Concentric Training

- Power – What It Is, Why We Want It, and How We Generate It

- Mixed Method Training May Develop Power Best

- What’s New On Breaking Muscle Today

References:

1. Turner, T., Tobin, D., & Delahunt, E. (n.d.). “Optimal Loading Range for the Development of Peak Power Output in the Hexagonal Barbell Jump Squat ,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 1627-1632.

2. Silva, B., Simim, M., Marocolo, M., Franchini, E., & Mota, G. (2015). “Optimal Load for the Peak Power and Maximal Strength of the Upper Body in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Athletes,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(6), 1616-1621. Retrieved July 7, 2015.