For several decades now, the fitness game has been blessed with commercial fitness and “wellness” centers (whatever that means). The first thing you notice when you enter one is an endless supply of machines, most of which can only exercise one body part in one motion.

Now, I’m not going to do a long free-weights-versus-machines rant. That has been done many times and by much more articulate people. What I am going to explore is how the novice is slyly conned by the manufacturers of these machines.

RELATED: An Argument Against Machines: RIP Weight Machines (1963–2013)

The Problem of Mechanical Advantage

Whether we are novices or Olympic medalists, we all like to lift more weight. It satisfies the ego and is an innate part of the human condition. Nothing wrong with that. Strength athletes need something to measure their progress with and the amount of weight on the barbell or machine seems to be an objective way of doing this. Since this seems obvious, you are probably wondering how the manufacturers of weight machines (and by extension those who purchase them for their facilities) find a way of conning you.

Let’s start with the weight stacks used in many of the machines. Most weight stacks are fairly accurate. Some have been discovered to be slightly lighter than advertised, but this is not the main way you will be fooled. Any variances of this type are not that significant enough to worry the prospective gym member.

LEARN MORE: How High School Physics Can Help Us With Our Weightlifting

Where the real problems occur is in the mechanical guts of the various machines. It is fact that the makers build in a certain amount of mechanical advantage to their wares. Do you remember this term from high school physics? You likely at least remember this is what makes a machine desirable in the first place. The whole idea is that a machine can move more resistance than the effort put into it.

Levers, Pulleys, and Inclines

That works well in the industrial world, but in the gym things are a bit different. Trainees are told to keep track of their workout poundages in order to track progress. This makes the figures they enter into those little books very important. And as we’ve all been trained to be good little consumers, we like to think we are getting our money’s worth.

“The whole idea is that a machine can move more resistance than the effort put into it.”

In the gym, that means that our effort should equal the machine’s resistance, not that resistance be far greater than effort. We want that 1:1 ratio. What goes in must equal what comes out. But that is not what happens with many of these machines in gymnasiums today.

If you also remember from physics, machines can be divided into levers, pulleys, and inclines. The observant gym members will note that all of these can be used on various machines. If they are even more observant, the gym members will notice that seldom do they experience a 1:1 ratio of resistance to effort.

Almost all of the machines give the user a little bit of help, making the ratio anywhere from 2:1 to 5:1. Many machines utilize not just one such assistance device, but often two or even more, each with its own mechanical advantage. You must then multiply them all to get the total mechanical advantage. Let’s look at each type of machine separately.

WRITE IT DOWN: Coaching Tip: The Importance of Journaling

The Overhead Press Machine

This machine is based on a simple second-class lever. The fulcrum is at one end, the effort is at the other, and the resistance somewhere in the middle.

The trainee presses up on the ends of the lever while the weight is attached to somewhere closer to the fulcrum. Our mechanical advantage is simply the ratio of the distance the lifter’s hands are from the fulcrum (A+B in the graphic below) divided by the distance the weight/resistance (W) is from the fulcrum (A).

The machine in my gym has a 4:1 mechanical advantage. Let’s say a trainee selects 200 pounds and rattles off a nice set of ten reps. If he forgets his high school physics, he is going to feel pretty strong. But should he? By now you should know that he shouldn’t. All he really did was fifty pounds for ten reps, nothing too impressive to someone who could do the same with a 200-pound free weight.

The Pulley Machines

Some of these are honest and some of them are not. How can you tell? Remember what your physics teacher said – and count the number of supporting cables.

RELATED: Why You Can’t Compare Resistance and Repetition Efforts

More than one cable means you do have a mechanical advantage. Many machines have two supporting cables and some even have three, often hidden so that counting them is difficult. To be fair, some machines label the stacks to compensate for this.

In addition, some machines have not only an advantageous lever, but it is attached to a 2:1 pulley system. In that case, you feel very strong as you write down your day’s poundage.

The Incline Leg Press Machine

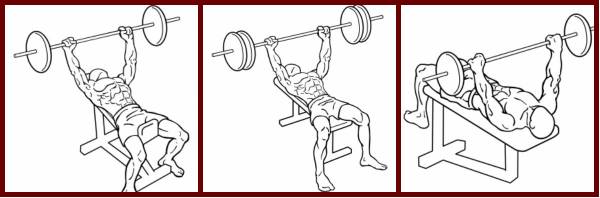

We all know that we can incline press a little more than we can military press, but not as much as we can bench or decline press. This is a good illustration of the effects of force vectors.

Left: Incline Press; Middle: Bench Press; Right: Decline Press

But there is another machine in the gym where this incline idea is used more insidiously. You all know what I’m talking about. It’s the leg press machine, the favorite of squat dreaders everywhere. Some truly awesome poundages can be moved on this device and they are all very gratifying to the ego. Even former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright boasted of a 400-pound leg press, and she was in her seventies at the time.

But those who want to do leg presses instead of those nasty old squatsshould be aware of one thing. Most leg press machines made today are built with tracks moving at a 45-degree angle. Back in the 1950s, we leg pressed lying on our backs and resting a barbell across the bottoms of our feet. This was a stupid thing to do, of course, but it had one advantage. It at least gave us some honest reading of what we were pressing.

“This is more or less completely safe and you can move tremendous weights on it. The trouble is you are not lifting as much as you think you are.”

But today we have something better – the leg press sled on a 45-degree angle track. This is more or less completely safe and you can move tremendous weights on it. The trouble is you are not lifting as much as you think you are.

To determine the actual weight, you have to take the cosine of the angle the machine deviates from the vertical. The gentler than angle, i.e., the more it deviates from the vertical, the easier it is to lift. Most leg press machines today are on 45-degree angles, although some are far gentler. The cosine of 45 degrees is about 0.71, giving a 1:1.4 mechanical advantage. This means that Ms. Albright’s 400-pound leg press is really only 285 pounds if she did it on a 45-degree angle.

Look Past the Numbers

I’m not sure if the manufacturers were thinking of this, but I’m sure it occurred to somebody that a mechanical advantage could be turned into a financial advantage. People like to move big weights and most don’t care about the engineering niceties.

RELATED: Globo Gym Warning: How to Protect Yourself, Your Money, and Your Goals

The gym owners who buy these machines are well aware that progress is best proven with impressive figures. And maybe it doesn’t bother the average trainee as long as they can see progress. Being able to lift eleven plates in the stack is still better than being able to lift ten. Whether it’s 110 pounds or 110 “something-or-others” makes little difference since it’s still more than 100.

Serious trainees will not be fooled, but they’re a minority anyway. And this is yet another reason why free weights have enjoyed a renaissance even as the machines have taken over in commercial gyms.

Photos 1 & 4 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 courtesy of Shutterstock and Breaking Muscle.

Graphic 3 courtesy of Everkinectic.