Most career coaches will work with an asthmatic client at some point. So, it’s important to understand asthma, its pathophysiology, and how exercise affects those who have the condition. Regular exercise can do wonders for those who suffer from asthma, but it’s vital that coaches understand how to safely work with asthmatic trainees.

Pathophysiology of Asthma

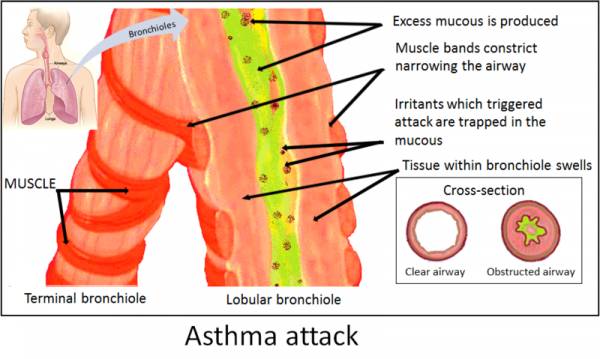

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disorder, characterized by reversible obstruction to airflow and increased bronchial responsiveness to a variety of stimuli, both allergic and environmental. Asthma has the following characteristics: recurrent respiratory symptoms, variable airflow obstruction, presences of airway hyperactivity, and chronic airway inflammation.

Environmental factors contributing to asthma could include being in areas with high pollen or places with a lot of pollutants in the air (usually big cities). In an asthmatic who has an allergic response, the allergen combines with antibodies on mast cells or basophils in the lungs. As a result, these cells release inflammatory chemicals such as leukotrienes and histamine. These chemicals then cause constriction of smooth muscle in the walls of the tubes that transport air throughout the lungs.

The exact causes of asthma are unknown, but asthma and allergies are often common amongst family members. It is known that multiple genes contribute to a person’s susceptibility to asthma. Genes on chromosomes five, six, eleven, twelve, and fourteen have all been linked to asthma.

In 2005, public health surveillance data estimated that 22.2 million Americans suffered from asthma, including 6.5 million children less than eighteen years of age and 15.7 million adults over eighteen years of age. The frequency, severity, length of occurrence, triggers, and symptoms of asthma vary from person to person. For some people asthma is a chronic condition, and for others symptoms only occur when provoked by stimuli such as allergens, stress, or even exercise.

Asthma and Exercise

Aerobic exercise can trigger an episode of asthma, and this is called exercise-induced asthma or EIA. It’s important to mention that most studies suggest exercise is not only safe and effective for individuals with asthma, but for some people exercise may even help control the frequency and severity of asthma attacks.

One such study was discussed in the International Journal of Sports Medicine. Since leukocytes play a central role in asthma physiopathology, this study tested aerobic training and the amount of leukocytes in asthmatic patients. Researchers tested the effects of four weeks of aerobic training on airway inflammation, pulmonary and systemic Th2 cytokine levels. In addition, leukocyte expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory, pro-fibrotic, oxidant, and anti-oxidant mediators in an experimental model of asthma were investigated.

The researchers concluded that aerobic training reduces the activation of peribronchial leukocytes, resulting in decreased airway inflammation and Th2 response. Most studies suggest that individuals who participate in an average of twenty to thirty minutes of aerobic exercise two to three times per week will improve maximal ventilation, oxygen consumption, work capacity, and heart rate. There is little evidence to support the idea that exercise worsens asthma symptoms or that there is any reason for the majority of individuals with asthma to avoid regular physical activity altogether.

Coach’s Corner: Understanding EIA or Exercise-Induced Asthma

EIA is characterized by transient airway obstruction that usually occurs five to fifteen minutes after physical exertion. Symptoms of EIA include wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, chest discomfort, or a combination of these. Symptoms can last up to thirty minutes following the cessation of exercise.

A small percentage of patients with EIA experience a late onset reaction (i.e. further episodic airway obstruction about four to six hours later). This late onset reaction of EIA is not fully understood, but is likely related to respiratory heat loss, increased osmolality caused by respiratory water loss, or associated vascular events, all triggered by an increase in ventilation during exercise.

The prevalence of EIA in the general population is low, only about 3-10%. That being said, most individuals diagnosed with asthma will experience EIA at some point in their lives. So as coaches, when looking into an exercise program for an asthmatic patient, it may be useful to group them into one of these categories:

- Exercise-induced asthma without other symptoms

- Mild asthma (ventilator limitation does not restrain submaximal exercise)

- Moderate to severe asthma (ventilator limitation restrains submaximal exercise)

As coaches, it’s important to know when the onset of asthma symptoms via exercise may occur. To produce asthmatic symptoms, the amount of physical exertion required is usually equivalent to a relative work rate of 75% of the age-predicted maximal heart rate (HRmax). Even though it is often thought that age-predicted HRmax is 220 – age, it was revisited by the University of Colorado’s Department of Kinesiology and applied Physiology. The conclusion of the study suggested that the regression equation to predict HRmax is 208 – 0.7 x age for adults, and that the older equation underestimates HRmax in older adults. The standard for HRmax is still 220 – age, but know scientists are debating the accuracy of this formula.

For an asthmatic, it may be beneficial to use the Karvonen Formula to find a target heart rate (since it takes into account resting heart rate). The formula is:

((Max Heart Rate – Resting Heart Rate) x %intensity) + resting heart rate

Understand that in those with severe asthma, a very mild exertion can provoke airflow obstruction and trigger EIA. It’s important to understand all of the factors involved with this condition order to provide a safe working environment for your asthmatic athletes.

Exercise Programming for Asthmatic Athletes

Athletes with asthma are going to differ from person to person. Individuals with asthma have periods of intermittent exacerbations and remissions that impact their ability to exercise. A coach writing programming for this clientele must set realistic goals and targets that may include improvement in any of the following:

Athletes with asthma are going to differ from person to person. Individuals with asthma have periods of intermittent exacerbations and remissions that impact their ability to exercise. A coach writing programming for this clientele must set realistic goals and targets that may include improvement in any of the following:

- Fitness as judged by usual physiological criteria

- Exercise tolerance

- Musculoskeletal conditioning (i.e. daily kinetic function and activities of daily living)

An area of importance for programmers to take into account is exercise intensity. The tolerance for intensity will vary significantly for asthmatic athletes. It’s usually recommended that six weeks be taken during which individuals with asthma learn to self-monitor their exercise intensity. During this time the client should have the safety of a coach on hand in case asthmatic symptoms occur.

It’s recommended that asthmatic individuals regulate exercise intensity using the Borg CR-10 scale or a visual analog scale to assess the intensity of breathlessness associated with physical activity. The Borg CR-10 scale is distinct from that used for perceived exertion and uses a one-to-ten grading of dyspnea severity. When athletes with asthma have familiarization with this scale, it helps reduce their fear of difficult breathing during physical activity.

Remember that even though an individual has asthma, it does not mean exercise is impossible for him or her. In many cases, exercise can help asthmatic individuals live fulfilling lives and even ease their symptoms. The place in which to start exercise will vary depending on whether the trainee lives a sedentary versus a fairly active lifestyle. Someone with asthma who is already fairly active will be able to do new activities that may be more strenuous.

For those of you dealing with asthma, keep your coach informed and learn as much about exercise and your condition as possible. And for you coaches, the more you know about the pathophysiology of asthma, the more likely you will be able to keep your athlete safe and offer a safer environment for those suffering from the condition.

References:

1. Clark, Christopher J and Cochrane, Lorna M., “ACSM’s Exercise Management for Persons With Chronic Diseases and Disabilities,” (Illinois: Human Kinetics, 2009), Kindle Edition, Chapter 19

2. Tate, Philip., “Seely’s Principles of Anatomy and Physiology,” (New York: McGraw Hill Companies, 2009), 616-617

3. Vieira, R. P. et. al., “Exercise Deactivates Leukocytes in Asthma,” International Journal of Sports Medicine. (2013): eFirst, accessed December 8, 2013.

4. Tanaka, H and Monahan, KD et al., “Age Predicted Maximal Heart Rate Revisited,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology. (2001): 153-156, accessed December 11, 2013.

5. Werner, Ruth., “Guide to Pathologies Third Edition,” (Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2005), 400-403

6. Baechle, Thomas and Earle, Roger., “Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning Third Edition,” (Illinois: Human Kinetics, 2008), 493-495

Photo 1 by By 7mike5000 (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 2 by By 7mike5000 (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via WIkimedia Commons.

Photo 3 courtesy of Shutterstock.