It’s time to talk about a serious condition: Imaginary Lat Syndrome (ILS). According to Urban Dictionary, ILS is the imaginary sensation of having huge latissimus dorsi muscles or “lats.” Weak deadlifts, squats, bench press, and slow running are serious symptoms of this pandemic that affects most modern day lifters. Luckily, the serious issue of ILS is easy to diagnose. Walking with your arms away from your body in an effort to look like a bodybuilder, when in fact you do not resemble one, is a clear sign of ILS.

Although this is an imaginary ailment, many people do neglect to train the back, and I’m not just talking about the part of the back that gives you “wings.” I am talking about the part of our body that made a punch by Mike Tyson so devastating, Bo Jackson so powerful, and the most important muscles for building efficient, high-speed running.

Think about how you train your own back. Most of us perform some type of row variation in an attempt to target our lats, but never quite train the whole muscle. Do you ever recall an intense cramping sensation coming from the lower portion of your lats? If you are like the other 99% of coaches and civilians out there who have never been able to access or feel this phenomenon, then this article is for you.

The lats are the largest muscles in the upper body, and connect at five different points including the spine, pelvis, ribs, scapula, and upper arm. Because of the variety of connections, they play a primary role in all strength exercises, even if they aren’t trained directly. Take a look at the fiber orientation of these muscles. Notice how these fibers are neither horizontal nor longitudinal. The diagonal fiber orientation is an excellent blend of both, which allows the lats to accommodate a wider variety of more complex movements and stability demands. Our lats have a huge cross-sectional area, a broad spectrum of attachments, and a unique fiber orientation that accommodates diverse movements.

What Your Lats Mean for Your Lifts

As coaches, we all know the critical importance of training these larger muscles in both athlete and civilian clients. The last thing we want is to create asymmetries that result in hunched-over backs caused by the overdevelopment of the chest and shoulder muscles. Let’s take a look at the globally agreed upon use of the lats during weight room activities by coaches like Dr. Stuart McGill, Kelly Starrett, DPT, and Dr. Robin McKenzie.

Squat

During the squat, the lats are used to stabilize the bar on your back, maintain an upright torso, and protect your spine. As with all multi-joint weightroom exercises, joint stabilization is key for spinal health and more efficient movement. As an added bonus, stabilization of your spine and pelvis will enable an improved range of motion in your squat.

To engage the lats during the squat, pull the bar down on your upper traps as if you are attempting to bend the bar in half. Do this by pointing your punching knuckles towards the ceiling while maintaining straight wrists, then position your elbows directly under your fists and pull them down and toward your hips.

Deadlift

The lats play a similar role in the deadlift as they do during squats. In order to maintain proper position and a flat back, you must engage the lats. Proper engagement will allow you to drop your hips and bring your chest up.

To engage the lats correctly, think of trying to pull your shoulder blades down into your back pockets. If you like juice as much as Dan John, use his cue to pretend like you have oranges under your armpits and attempt to squeeze the juice out to ensure those lats are packed nice and tight.

Bench Press

During the bench press, your lats work to provide spinal stabilization and help transfer force. One of the most often overlooked aspects of bench strength is the use of our backs. If your back isn’t tired after a bench press workout, you didn’t bench correctly.

In order to take full advantage of your lats, you must drop your elbows down to a 45° angle. This protects your shoulders by assigning the load to your lats, and it allows you to more effectively transfer force from your legs into the bar.

The Properly Positioned Spine

Many times, problems with these exercises will be interpreted as a lack of mobility or flexibility, but in reality, the issue has to do with positioning. Organizing your spine in a braced, stable position will increase range of motion significantly. According to Kelly Starrett, a properly positioned spine looks like this:

- The pelvis is set in a neutral position. The simplest and most effective way to put your pelvis into the correct position is by contracting your glutes.

- The ribcage is drawn down. With your glute muscles 100 percent engaged, tilt your lower ribcage down into a balanced alignment with your pelvis. Imagine that both your pelvis and your ribcage are bowls of water and you don’t wish to spill a drop.

- The glutes and abs are dialed down. With your pelvis and ribcage aligned, keep your abdominal and glute muscles turned on at 20 percent tension in order to lock things in place.

- Your head is in a neutral position. Center your head over your shoulders, not down or back, and balance it in a neutral position with your gaze forward.

- Your shoulders are stabilized. Screw your shoulders into a stable position by extending the tips of your shoulder blades down toward your hips.

Head Over Foot

Setting up in this manner allows the spine to become a channel for the power generated by the hips and shoulders for weightlifting. But what about for athletic movements and running? Traditional coaching cues runners to keep the sternum stacked directly over the pubic symphysis in order for the force of the hips to translate into the rest of the body. Otherwise, you’re not running as swiftly and efficiently as you can, and you’re opening yourself up to greater risk of an overuse injury.

None of the world’s best and fastest athletes from a myriad of sports run with a braced core. Even Usain Bolt, the fastest man in recorded history, shifts his head dramatically from side-to-side while he smashes world records. So, how do you begin to tap into the speed of Bolt or the power of Tyson? The answer is by coiling your core with head-over foot-technique.

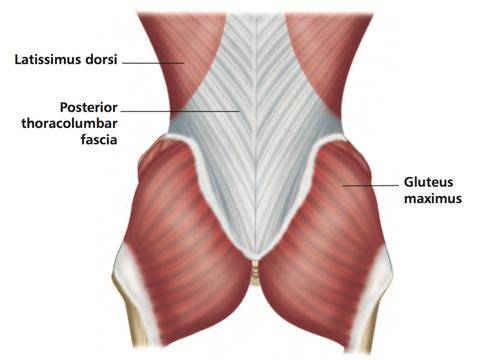

It’s all about biomechanics. Because the spine is as curved as it is, flexion in the frontal plane (side-bending) causes axial counter-rotation of the spine in the transverse plane. Side-bending to the left causes the left shoulder to rotate down and back and the left hip to rotate up and forward. The lats are essential when coiling your core due to their connection with the thoracolumbar fascia (TLF). Consequently, inhibition of the latissimus dorsi can cause compensations in the neck, shoulder, elbow, lower back, and gait. How does this happen?

When the body perceives instability in a joint, it will very often either compress that joint or a nearby joint. In the case of the elbow, inhibition of the lat causes the elbow to compress in order to stabilize the shoulder joint, many times resulting in tennis elbow. The biggest victim, however, is our lower backs. Since the lats are contiguous with the TLF, any inhibition of the lat will cause compensations in our muscles and their function. These include the muscles of the ipsilateral erector spinae group, the quadratus lumborum, the gluteus maximus, and the gluteus medius. This inhibition may also cause a contralateral rotational compensation, including the piriformis. This fascia is a critical attachment point through which several muscles can exert their desired effects.

Getting Around Restrictions

Take a look at the picture below. You can easily recognize the TLF and lat, but look at the way that the gluteus maximus’ fibers are oriented. If those forces are transferred across that TLF, they go right into the “wheelhouse” of the gluteus maximus. In other words, they work synergistically, linking one shoulder with the opposite hip. Thomas Myers goes even deeper in his book, Anatomy Trains. He discusses the spiral line, a fascial connection between the shoulder and opposite leg, from the hip to the ankle. If you have restrictions in the spiral line, both ends of the line will be negatively affected.

If the inhibited lats and fascia can cause such global problems, then they can also facilitate explosive movements when open and working properly. The key to the best utilization of our core while running is to use the spine. By using the WeckMethod Sidewinder drill and cuing athletes to place their head over their foot (HOF), we can coil the core and utilize the lats in a few easy steps. In the video below, David Weck gives a detailed explanation on how we accomplish this task.

Enhance Every Movement

In the case of the WeckMethod Sidewinder drill, we focus on coiling training to enhance the contralateral serape effect to take full advantage of our spiral line. Our core is directly related to how fast and efficiently runners run, fighters fight, and rotational sports throw. The head over foot training technique enhances every movement. Our coiling core is crucial in force production and maintaining balance. Understanding how these patterns are formed and relate is necessary to make every step stronger.

References:

1. Murphy, T.J. “A Runner’s Secret to Maximum Force Production: The Organized Spine.” STACK. January 20, 2014. Accessed 2017.

2. Myers, Thomas W., and Susan K. Hillman. Anatomy Trains. London: Primal Pictures Ltd., 2004. Print.