Coaches, athletes, and workout fanatics are in a perpetual search for competitive advantages both on and off the field. The offseason is paramount for the development of an athlete’s physical strength and psychological performance.

Coaches, athletes, and workout fanatics are in a perpetual search for competitive advantages both on and off the field. The offseason is paramount for the development of an athlete’s physical strength and psychological performance.

More specifically, improvement in anaerobic power is seen as a primary factor in athletic success, and anaerobic energy is essential to perform sprints and high-intensity runs, all of which contribute to your muscular gains and a game’s final result.1

Given that typical football, volleyball, and soccer games last anywhere from 60-90 minutes, it also makes it important for players to include some muscular endurance exercises in their strength training routines.

These intense physical demands come with a high price that can only be paid for through proper recovery.

Most of us have heard the phrase, “There is no such thing as overtraining, just under recovering.” While this may be true, how many of us have the time to implement all of the suggested recovery tools necessary for our health?

Although there are as many recovery techniques on the market as there are exercises, qigong (chee-gong) presents a unique and previously unexplored method to eliminate the negative effects of stress and give you a 25% increase in strength in 8 weeks.

The Damage of Workouts

In order to understand the complexity of some of the popular recovery tools, we need to first take a glimpse into the effects our workouts have on our bodies. Muscular adaptation to physical exercise has previously been explained by the classical damage–inflammation–repair pathway.

Muscle damage brought on by physical exercise can be expressed through fatigue, inflammatory reactions, high serum levels of muscle-injury biomarkers (creatine kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, myoglobin), oxidative stress, and delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS).2, 3, 4

These biomarkers and ensuing symptoms peak 24-48 hours post-exercise, and can impair muscle function and physical performance for up to 7 days.3, 5, 6

The prevention and treatment of DOMS are important issues for exercise programs. The use of anti-inflammatory non-steroidal drugs (NSAIDs), stretching, compression therapy, ultrasound, acupuncture, deep tissue massage, nutritional supplements, anti-oxidants, and electrical stimulation have all been tested, with varying degrees of success, for reducing DOMS symptoms.9, 10, 11, 12, 13

However, there is no consensus about the most suitable method for effectively preventing DOMS and muscle injury.

Inflammation is the body’s initial non-specific response to a wide variety of tissue damage produced by mechanical, chemical, or microbial stimuli. The mechanical stress on cellular cytoskeletons triggers acute inflammatory responses, increasing local and systemic markers of inflammation such as interleukin 6, and C-reactive protein.

The Eastern Model of Organ Function

Given these inflammatory reactions and muscle damage, recovery methods are critical for athletic performance. While the precise mechanism through which qigong is able to decrease inflammation is unclear, one possible pathway is through its effect on the immune system. Several studies have indicated that qigong leads to improved immune function.7, 8

Traditional Chines Medicine’s (TCM) concept of an organ is much broader than the Western concept. While Western anatomy and physiology are primarily concerned with the physical body in its most concrete forms, the focus of energetic anatomy and physiology in TCM is on the underlying patterns of energy that animate and sustain the physical form.14

Given the conceptual differences between Western and Eastern medicine, it is paramount to build connections between the two philosophies.

The Liver

The liver is involved in a wide range of metabolic and regulatory functions, and is one of the most important organs in the body for maintaining the health of the blood. The various functions can be categorized into the following areas:

- Metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins and lipids

- Storage of vitamins and minerals

- Phagocytosis

- The removal of poisons, drugs, and certain hormones

The functions of the liver described in TCM are similar to those described in Western medicine. However, TCM asserts that the liver also stores and regulates the blood, smooths and regulates the flow of “qi” (the circulating life force or energy), governs the tendons, and has specific emotional influences.

In the TCM model, during exercise, blood flows into the muscle to nourish the muscle tissue, allowing it to become more pliant. When the muscles are well-nourished by the blood, the body maintains a stronger resistance to attacks from external pathogenic factors. After the completion of exercise, the blood flows back into the liver, allowing the body to restore and recharge its energy.

The liver’s most important function in TCM is the regulation of qi throughout the entire body.14

The liver governs the circulation of qi through all of the body’s internal organs, as well as regulates the function and control of the tendons and ligaments via the contraction and relaxation of the muscles. Thus, the liver is seen as the source of the body’s physical strength.

If the qi-filled blood from the liver becomes deficient, the body will be unable to moisten and nourish the tendons, which often results in symptoms such as muscle cramps, spasms, and an overall lack of strength.

The Lungs

Respiratory function is paramount for success in athletics, with the primary purpose being to deliver oxygen to the cells, while removing carbon dioxide.

Therefore, the smooth operation of the cardiopulmonary system is of critical importance. Blood must flow with efficiency from the heart into the lung tissue, where it is oxygenated, then throughout the rest of the body.

Anatomically, the lungs surround the heart, but in TCM they surround the heart energetically as well.14 According to TCM, one of the main functions of the lungs is to govern the qi and respiration.

Specifically, the lungs send qi into the heart and down in to the kidneys. The lungs also regulate breath, controlling both pulmonary and cellular respiration, and are the main organs responsible for gathering “heaven qi,” which is made up of the forces that the heavenly bodies exert on the earth, such as sunshine, moonlight, and the moon’s effect on the tides.

It is through respiration that qi and gasses of the body are exchanged between the interior and exterior of the body. Breathing in oxygen from the air during inhalation, and expelling gaseous wastes such as carbon dioxide during exhalation, maintains healthy internal organ regulation. Through this exchange, the body’s energetic and physical metabolism function smoothly.

Psychological Factors and Balance

In addition to the physiological concern of DOMS discussed earlier, there are also psychological factors that influence winning or losing in sports. The influence of stress and anxiety in sport performance is significant.

The athlete’s optimal state of mind depends on the relationship between anxiety and performance, and the factors that facilitate it. Once a stress response is produced, physiologic and attentional changes occur, such as increased muscle tension, narrowing of the visual field, and distractibility, thereby increasing likelihood of injury.15

One foundational concept of TCM that is familiar to most Westerners is the idea of yin and yang. In TCM, the theory of yin and yang energy represents the duality of balance and harmony within the body, as well as within the universe.

Yang manifests as active, creative, masculine, hot, hard, light, heaven, white and bright. Yin manifests as passive, receptive, feminine, cold, soft, dark, earth, black, and shadow. When the body is in balance between yin and yang, health is predominant. In athletes, if the body and environment are out of balance, performance, recovery, and clarity can be disrupted.

TCM views emotions as potential “internal pathogens” that have the ability to unbalance the function of our organs. This disruption can occur when we experience an emotion very intensely, suddenly, or when we chronically hold onto any emotion over an extended period of time.

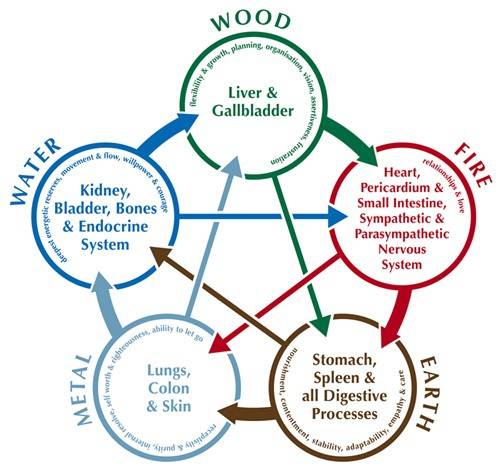

Given the need for emotional balance and the effects of emotional imbalance on each organ system, TCM’s Five Element model (Fig. 1) is useful to organize everything into interacting, comprehensive patterns. This model establishes which emotion corresponds to an internal organ, and that each organ is very much affected by its related emotion.

From the TCM perspective, emotions must flow unobstructed in order to not have an adverse effect on your wellbeing. This wisdom is clearly stated in the Nei Jing, a classic text of TCM, written some 2,500 years ago: “Overindulgence in the five emotions—happiness, anger, sadness, worry, and fear—can create imbalances.”16

The Five Elements are an ancient philosophical concept created to explain the composition and phenomena of the physical universe. They were later adapted in TCM to illustrate the unity of the human body and the natural world, and the physiological and pathological relationship between the internal organs.17

Through modern holistic practices such as acupuncture, Eastern medicine can now provide an understanding that emotions are powerful energies that strongly affect our qi and our overall health.

Figure 1. Five Element Theory. The five elements in Chinese medicine.18

The Five Elements and the Body

In TCM, the lungs are represented by metal, and function much in the same way as described in Western medicine. However, TCM expands the role of the lungs to include psycho-emotional aspects of integrity, attachment, and grief.

As a consequence, if the circulation of qi becomes obstructed for long periods of time, the lung qi stagnation can give rise to chronic emotional turmoil, sometimes manifesting through disappointment, sadness, grief, despair, shame, and sorrow.

Represented by wood, the liver’s function of ensuring the flow of qi has an influence on the body’s mental and emotional states that each organ generates. If the circulation of liver qi becomes obstructed, the resulting stagnation gives rise to emotional turmoil.

For instance, anger—which also includes feelings of stress, frustration, bitterness, and resentment—directly impacts liver function. Anger makes qi rise, so many of its effects will be felt in your head and neck: headaches are the most common symptom, but dizziness, ringing in the ears, red blotches on the front of the neck, and thirst can all be signs of a liver imbalance.

In Western medicine, the spleen’s primary functions are to cleanse the blood, fight infection, and store and release platelets and white blood cells. The spleen can easily be injured as a result of local impact trauma or severe infection. As a precaution, Western medicine will remove the spleen in cases of leukemia or lymphoma.

In TCM, the functions attributed to the spleen, represented by earth, are completely different than those identified by Western medicine.

From an energetic perspective, some of the main functions of the spleen are to rule the muscles and tendons, and to distribute emotional and spiritual nourishment.

If the spleen is unable to nourish the muscles and tendons, the muscles will become weak and begin to atrophy. Emotionally, when the spleen qi becomes stagnant, this can give rise to emotional turmoil such as obsession and doubt.

The functions attributed to the heart, represented by fire in TCM, also differ from the functions described by Western medicine. Chinese energetic functions include those associated with the circulatory system, as well as emotional aspects.

The qi of the heart is the driving force for the heart’s beat, rhythm, rate, and strength. Eastern and Western medicine both agree that the heart pumps blood through arteries to be delivered throughout the body.

However, TCM expands on this basic concept, and sometimes calls the heart “the controller,” since it coordinates all of the energetic and emotional functions of the body.

When qi is flowing normally, an individual will experience peace in his thoughts and actions. On the other hand, if the circulation of qi is obstructed, this stagnation can give rise to nervousness, anxiety, panic, and guilt.

Western medicine and TCM have differing views regarding the functions of the kidneys, represented by water. In Western medicine, during exercise, skin and active muscle tissue compete for a limited cardiac output.

The increased blood flow to the skin, along with the evaporation of sweat, allows heat to be dissipated to the environment, while increased blood flow to the muscle allows for the delivery of oxygen and energy substrates.

In order to accomplish this dual purpose without a decrease in blood pressure, blood flow to the liver, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, and kidney are reduced.19

This results in increased sodium and water conservation by the kidneys, and the maintenance of mean arterial pressure during exercise. While these adjustments are beneficial for homeostasis, excessive reductions in renal function can precipitate renal failure.20

According to TCM, the main energetic functions of the kidneys include the function of the urinary system, the nervous system, emotional aspects, and spiritual influences.

Emotionally, the kidneys provide the capacity and drive for strength, skill, and hard work.

An individual with healthy kidneys will have the ability to work hard and purposefully for long periods of time. However, when the kidneys are in a state of disharmony, the individual may have deficient strength, endurance, confidence, and willpower.

Qigong: Balancing the Elements

Given the importance of the Five Element theory and the disruptions that arise due to emotional disharmony, qigong aims to cultivate life force through regular effort, and often combines movements and mind focusing.21

It is considered to be the contemporary offspring of some of the most ancient healing and medical practices of Asia. Earliest forms of qigong make up one of the historic roots of contemporary TCM theory and practice.22

Qigong purportedly allows individuals to cultivate the natural force or energy (qi) that is associated with physiological and psychological functionality.23

Qi is the conceptual foundation of TCM in acupuncture, herbal medicine, and Chinese physical therapy. It is considered to be a universal resource of nature that sustains human wellbeing and assists in healing disease, as well as having fundamental influence on all life, and even the orderly function of celestial mechanics and the laws of physics.

Qigong exercises consist of a series of orchestrated practices including body postures and movements, breath practice, and meditation. They are all designed to enhance qi function by drawing upon natural forces to optimize and balance energy within, through the attainment of deeply focused and relaxed states.

From the perspective of Western thought and science, qigong practices activate naturally occurring physiological and psychological mechanisms of self-repair and health recovery.23

The philosophy of qigong exercise is that the mind “guides” the person’s qi to a healthy state. If the flow of qi is disturbed, illness may occur.21

Entering the “qigong state,” being deeply relaxed, may trigger the relaxation response that supports an individual’s recovery process.24

The Study: The Effect of Qigong on Performance

The use of mind-body therapies, such as tai chi, yoga, qigong, and meditation are well-studied, and frequently reported as a means of coping with anxiety and depression.25 Psychological benefits from regular qigong training include antidepressant effects,26 increased self-efficacy,27 and stress reduction.28

Despite these findings, there is little knowledge of the impact of qigong exercise on an elite athlete’s physical and mental states during training. Therefore, I conducted a study to determine the efficacy of qigong to facilitate strength gains and wellbeing in collegiate athletes—specifically the Dao Yin exercises focusing on lungs, kidneys, heart, liver, and spleen.

The aim of the study was to find out if qigong could be used to increase strength in collegiate athletes, with the potential to improve sport performance and reduce likelihood of injury.

If effective, this qigong exercise protocol could be implemented in high school, collegiate and professional weight rooms and athletic training rooms. The increased performance could even lead to higher monetary value for athletes choosing to play professionally after their collegiate careers are over.

No previous studies have examined the effects of qigong exercises on elite, anaerobically trained collegiate athletes.

Seventy-three athletes (47M, 26F, 18-22 years old) volunteered to participate in the study, and were divided into a qigong exercise group or a standard care group.

Each group underwent the same prescribed weight training program, which consisted of eight weeks of training, four days per week. Strength gains were measured through a vertical jump test and a 3RM front squat, bench press, and deadlift before and after the program.

Wellbeing was measured through a questionnaire, which was administered before, weekly, and after the weight training program. In addition to the training program and questionnaire, the qigong group performed qigong exercises five days a week for fifteen minutes each day.

The qigong group’s average strength values were higher versus the control for bench press (+ 52%; P= 0.00), deadlift (+15%; P= 0.09), front squat (+28%; P= 0.004), and vertical jump (+52%, P= 0.223). The qigong group also had a higher average overall wellbeing score (+6%; P= 0.00).

These data suggest that eight weeks of qigong exercises for 15 minutes a day, 5 days per week facilitates an improvement in exercise performance, as well as an enhancement in self-reported feelings of wellbeing.

Further studies examining the long-term benefits of qigong, the collection of inflammatory biomarkers, and any potential association between improvement in wellbeing and reduction in injury rates may provide additional information that may assist coaches and athletic trainers in providing optimal comprehensive care.

References:

1. Aziz, A. R., M. Chia, and K. C. Teh. “The relationship between maximal oxygen uptake and repeated sprint performance indices in field hockey and soccer players.” Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 40 (2000): 195-200.

2. Aoi, W., Naito, Y., Takanami, Y., Kawai, Y., Sakuma, K., Ichikawa, H., Yoshida, N. and Yoshikawa, T. (2004). Oxidative stress and delayed-onset muscle damage after exercise. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 37(4), pp.480-487.

3. Ascensão, A., Rebelo, A., Oliveira, E., Marques, F., Pereira, L. and Magalhães, J. (2008). Biochemical impact of a soccer match—analysis of oxidative stress and muscle damage markers throughout recovery. Clinical Biochemistry, 41(10-11), pp.841-851.

4. Iguchi, M. and Shields, R. (2010). Quadriceps low-frequency fatigue and muscle pain are contraction-type-dependent. Muscle & Nerve, 42(2), pp.230-238.

5. Chatzinikolaou, A., Fatouros, I., Gourgoulis, V., Avloniti, A., Jamurtas, A., Nikolaidis, M., Douroudos, I., Michailidis, Y., Beneka, A., Malliou, P., Tofas, T., Georgiadis, I., Mandalidis, D. and Taxildaris, K. (2010). Time Course of Changes in Performance and Inflammatory Responses After Acute Plyometric Exercise. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(5), pp.1389-1398.

6. Paulsen, G., Egner, I., Drange, M., Langberg, H., Benestad, H., Fjeld, J., Hallén, J. and Raastad, T. (2010). A COX-2 inhibitor reduces muscle soreness, but does not influence recovery and adaptation after eccentric exercise. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 20(1), pp.e195-e207.

7. Yeh, M., Lee, T., Chen, H. and Chao, T. (2006). The Influences of Chan-Chuang Qi-Gong Therapy on Complete Blood Cell Counts in Breast Cancer Patients Treated With Chemotherapy. Cancer Nursing, 29(2), pp.149-155.

8. Luo, S., & Tong, T. “Effect of vital gate qigong exercise on malignant Tumor.” In First World Conference for Academic Exchange of Medical Qigong, 1988. Beijing, China.

9. Arent, S., Senso, M., Golem, D. and McKeever, K. (2010). The effects of theaflavin-enriched black tea extract on muscle soreness, oxidative stress, inflammation, and endocrine responses to acute anaerobic interval training: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 7(1), p.11.

10. Best, T., Hunter, R., Wilcox, A. and Haq, F. (2008). Effectiveness of Sports Massage for Recovery of Skeletal Muscle From Strenuous Exercise. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 18(5), pp.446-460.

11. Cheung, K., Hume, P. and Maxwell, L. (2003). Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness. Sports Medicine, 33(2), pp.145-164.

12. Stay, J. C., M. D. Richard, D. O. Draper, S. S. Schulthies, and E. Durrant. “Pulsed ultrasound fails to diminish delayed-onset muscle soreness symptoms.” Journal of Athletic Training 33 (1998): 341-46.

13. Zainuddin, Z., M. Newton, P. Sacco, and K. Nosaka. “Effects of massage on delayed-onset muscle soreness, swelling, and recovery of muscle function.” Journal of Athletic Training 40 (2005): 174-80.

14. Johnson, J. A. Chinese Medical Qigong Therapy: Vol. 1 Energetic Anatomy and Physiology. Pacific Grove: n.p., 2002.

15. Williams, J. and Andersen, M. (1998). Psychosocial antecedents of sport injury: Review and critique of the stress and injury model‘. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 10(1), pp.5-25.

16. Maoshing, N. The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1995.

17. Beijing Medical College. Dictionary of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Hong Kong: The Commercial Press Ltd., 1984.

18. Ping Ming Health. (2017). The five elements in Chinese medicine – Ping Ming Health. [online] [Accessed 11 May. 2015].

19. Rowell, L. (1993). Human cardiovascular control. New York: Oxford University Press.

20. Buskirk, Elsworth R., and Susan M. Puhl, eds. Body Fluid Balance: Exercise and Sport. Vol. 9. CRC Press, 1996.

21. Chen, K. “Qigong therapy for stress management.” In: Lehrer, P.M., Woolfork, R.L., Sine, W.E., Principles and Practice of Stress Management. Guilford Press, New York, 2007, pp.428-448.

22. Jahnke, R. (2002). The Healing Promise of Qi. Chicago, IL: Contemporary Books.

23. Jahnke, R., Larkey, L., Rogers, C., Etnier, J. and Lin, F. (2010). A Comprehensive Review of Health Benefits of Qigong and Tai Chi. American Journal of Health Promotion, 24(6), pp.e1-e25.

24. Benson, H., M. M. Greenwood, and H. Klemchuk. “The relaxation response:psycho-physiologic aspects and clinical applications.” International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 6 (1975): 67-98

25. Wolsko, P., Eisenberg, D., Davis, R. and Phillips, R. (2004). Use of mind-body medical therapies. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(1), pp.43-50.

26. Tsang, H., Fung, K., Chan, A., Lee, G. and Chan, F. (2006). Effect of a qigong exercise programme on elderly with depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(9), pp.890-897.

27. Lee, M., Lim, H. and Lee, M. (2004). Impact of Qigong Exercise on Self-Efficacy and Other Cognitive Perceptual Variables in Patients with Essential Hypertension. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 10(4), pp.675-680.

28. Lee, M., Hong, S., Lim, H., Kim, H., Woo, W. and Moon, S. (2003). Retrospective Survey on Therapeutic Efficacy of Qigong in Korea. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine, 31(05), pp.809-815.