A study1 out of the University of Leuven in Belgium, published in Frontiers in Physiology, tested 27 moderately trained subjects. The subjects were given nitrate supplement capsules in low oxygen, hypoxia, situations, and tested against a placebo group and normal oxygen situations. The supplements were given ahead of sprint interval training (SIT), which consisted of intense short cycling sessions 3 times a week. Nitrates are commonly found in green, leafy vegetables like spinach.

Intermittent hypoxic training (IHT) is becoming popular as a means to boost endurance and high-intensity exercise performance. You have probably come across people training in masks, referred to as normobaric hypoxicators. These masks simulate high altitude training for those of you stuck at sea level. There are studies2 that show high-intensity hypoxic endurance training can enhance muscle mitochondrial and capillary density. However, research3 into the effects of IHT on sea-level exercise performance is not clear cut with current studies implying that training intensity at higher levels involving anaerobic energy input may be more effective.

Nevertheless, exercising at high altitudes has become a training strategy for many athletes, despite the uncertainty of the efficacy of the regimen. To do intense workouts at high altitude you need to have high input fast-oxidative muscle fibers to sustain the power. The researchers in this study set to determine if making these these muscle fiber types stronger through nutritional intake would lead to better performance.

“This is probably the first study to demonstrate that a simple nutritional supplementation strategy, i.e. oral nitrate intake, can impact on training-induced changes in muscle fiber composition;” stated Professor Peter Hespel from the Athletic Performance Center at the University of Leuven.

Yet, Professor Hespel also says, that it remains to be firmly established that an increase in fast-oxidative muscle fibers will, eventually, lead to enhanced performance.

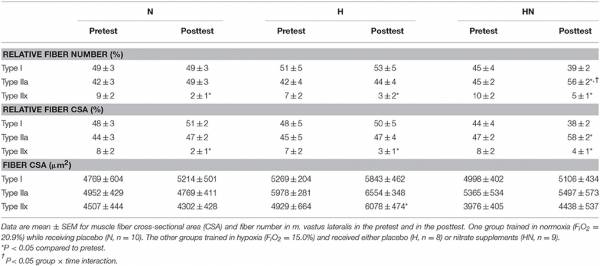

The study involved a test before (pretest) and after (posttest) a 5-week controlled SIT program. Subjects performed a maximal incremental VO2max-test on a cycle ergometer. The initial workload was set at 70 W and was increased by 30 W per min until volitional exhaustion. The highest oxygen uptake measured over a 30-s period was defined as the maximal oxygen uptake rate (VO2max).

Participants then cycled for 15 min at 50 W to recover, after which a 30-s modified Wingate test (W30s) was performed. In the second familiarization session, participants completed a 30-min simulated time-trial (TT30min). One group performed the SIT program in normoxia and received a placebo supplement (N). All other participants trained in hypoxia, with eight participants receiving a placebo (H) and nine participants receiving a nitrate (HN) supplement.

The experiments in this study showed that oral nitrate supplementation during short-term SIT did increased the proportion of type IIa muscle fibers in muscle, which improve performance in intense workouts. However, compared with SIT in normoxia, SIT in hypoxia did not generate beneficial physiological adaptations yielding enhanced aerobic or anaerobic capacity or performance.

He also cautions: “consistent nitrate intake in conjunction with training must not be recommended until the safety of chronic high-dose nitrate intake in humans has been clearly demonstrated.”

Future research is going to look at how much of an impact nitrate-rich vegetables have as an addition to normal athletic diets. Athletes push their bodies to the limit in order to achieve greater performance. Any natural dietary supplement that gives them an edge demands study. In the meantime, you probably won’t go wrong eating your greens. Although the jury is out on whether you need to mask yourself and deprive yourself of oxygen to get better at your chosen sport.

References

1. De Smet, Stefan, Ruud Van Thienen, Louise Deldicque, Ruth James, Craig Sale, David J. Bishop, and Peter Hespel. “Nitrate Intake Promotes Shift in Muscle Fiber Type Composition during Sprint Interval Training in Hypoxia.” Exercise Physiology, 2016, 233.

2. Geiser, J., Vogt, M., Billeter, R., Zuleger, C., Belforti, F., and Hoppeler, H. (2001). Training high-living low: changes of aerobic performance and muscle structure with training at simulated altitude. Int. J. Sports Med.22, 579–585.

3. Hoppeler, H., Klossner, S., and Vogt, M. (2008). Training in hypoxia and its effects on skeletal muscle tissue. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 18, 38–49.