How often have you finished a delicious meal, only later hours later to be plagued by uncomfortable bloating or an upset stomach? Perhaps your favorite treats routinely cause your stomach and digestive system to feel distressed, or maybe you notice a decrease in your energy levels during workouts after eating particular foods. We’ve all experienced unintentional consequences due to the consumption of specific foods—some of us more than others.

Naturally, when this occurs many of us want to fulfill our inner detective and uncover the mystery. It’s a bit trickier to do this than it might seem at first. When the cause of the problem is unclear, most people begin by eliminating what they believe to be the culprit. However, without an accurate way to evaluate exactly what this problem food is, you may not discover whether the food you eliminated was actually the solution to your problem—instead of some other confounding change you made to your diet in the process.

What follows are some guidelines to help you perform your own dieting experiments, accurately and effectively, to help uncover any food mysteries that might strike. It will be helpful for those plagued by constant negative side effects from their eating, as well as for anyone who simply wants to maximize their performance in the gym.

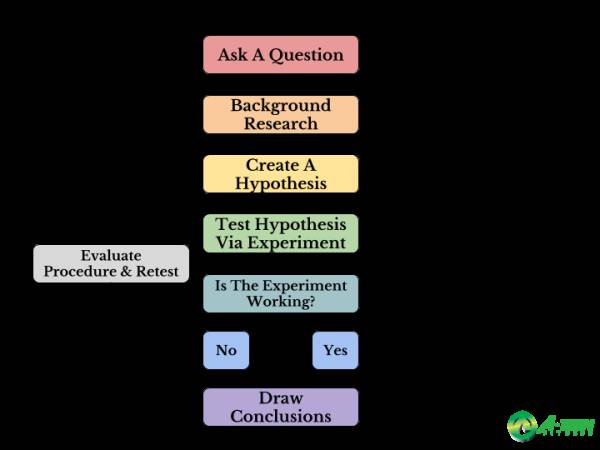

The Scientific Method

The scientific method is a concept we likely all learned in early grade school, but it is an important concept we should revisit, as it will set the entire framework for our dieting experiments. The ability to draw reasonable and accurate conclusions stems from the ability to follow the scientific method.

While most of us naturally complete a number of these steps, we often miss a few crucial pieces. Is it absolutely imperative to follow this model when we’re completing our own personal dieting experiments to feel or perform better? The short answer is yes. Failing to correctly identify the source of your issues could lead you to a life of avoiding foods that are actually harmless—potentially robbing you of the joy of eating them (or perhaps the convenience of not having to avoid them)—and, more significantly, failing to actually resolve whatever issues you are experiencing with your diet.

Let’s briefly go over what each step involves.

Step 1: Ask a Question

You eat a meal at a restaurant which causes you to feel bloated afterwards. You ask yourself, “What food did I eat that could have caused me to feel like this?” Boom, step one complete. The question lays the foundation for what problem we are trying to solve. Is it bloating? Fatigue in the gym? Hives?

Step 2: Perform Background Research

This is one area where many people misstep. We often begin to create hypotheses (or draw conclusions) based on commonly held beliefs (note use of the word beliefs instead of facts). Sometimes we have the pre-existing knowledge to fulfill this step, and other times we need to better understand what is known about the topic. For example, most adults know that lactose intolerance is a real thing that causes sufferers to avoid dairy. Therefore, if we eat a meal containing dairy and feel discomfort afterwards, we could create the hypothesis that it might be the dairy. (The prior knowledge of lactose intolerance makes it conceivable that dairy could be the culprit).

Other times we may have to do some online digging. In another example, did you know that the excessive consumption of many sugar alcohols can cause some of the same symptoms as dairy consumption does in those who are lactose-intolerant? Symptoms include gastrointestinal discomfort, gas, and diarrhea (in more extreme cases).

If the food contains both dairy and sugar alcohols, it can be easy to draft our hypothesis toward the more commonly held knowledge of lactose intolerance, especially if we are unaware of the information about sugar alcohols. Therefore, searching and uncovering all pertinent information surrounding potential causes is important to knowing which questions to ask.

Step 3: Create a Hypothesis

Once we have asked a question and uncovered all relevant information of the possibilities, we are now informed enough to make a prediction about the potential outcome of our experiment. From our example above, if you’ve never had a dairy intolerance prior, then sugar alcohols stand to be the more likely issue. (Developing a dairy intolerance later in adulthood is not unheard of so this remains a possibility, but probably a more unlikely one.)

Step 4: Test Hypothesis via Experimentation

This is another step where many people make mistakes. The key to a good experiment is being able to draw accurate conclusions of causality—meaning the manipulation of X caused the result of Y (and it wasn’t just a coincidence). The key to determining this causality is the ability to manipulate only one variable at a time. If you eliminated both dairy and sugar alcohols from your diet at the same time and began to feel better after your meals, then you wouldn’t be able to accurately say which variable (dairy or sugar alcohols) was causing the problem.

Simply put, most people change too many things at once. Ideally, you would eliminate only dairy (and keep sugar alcohols) to see if there was improvement. Then you could reverse and reintroduce dairy but eliminate sugar alcohols. Then you could try eliminating both. Does one make you feel worse than the other? Does eliminating both make you feel the best? Was there some other change in your diet (maybe you tried a new restaurant for lunch that day)? When engaging in a diet experiment, only change one thing at a time and keep everything else the same.

How long will it take for your diet experiment to provide valuable information, and when do you know when you should call it quits and head back to the drawing board? This will likely vary depending on what you’re testing for. If you’re trying to reduce bloating, for example, then you may notice improvements within a couple days. On the other hand, if you’re testing a possible gluten sensitivity it can sometimes take a few weeks for noticeable changes to occur. To be safe, I suggest you conduct your diet experiment for at least two to three weeks before reevaluating whether it was a success or not.

Step 5: Determine If the Experiment Is Working

Are you achieving the results you desire, whether that be feeling better or seeing improved performance? If the answer is yes, then congrats—your experiment worked and your hypothesis might be correct. If you aren’t achieving the results you wanted, then you should revisit your experiment and change the variables (but only one at a time) then retest. If you eliminated dairy but didn’t notice an improvement in your bloating, then you may need to go back, re-add dairy, eliminate the sugar alcohols, and try again.

Any time you need to retest your experiment, you will likely have to change your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was that dairy caused your issues, but then you test by eliminating dairy and you still feel bad, it doesn’t make much sense to retest with the same hypothesis that dairy is the problem, unless for some reason you think your testing method was flawed.

Step 6: Draw Conclusions

If your experiment worked, awesome! Now you get to draw conclusions based on what you found. You eliminated dairy and still felt horrible, so you go back and eliminate sugar alcohols instead (keeping everything else the same) and feel better. Now you can more reasonably conclude that eliminating sugar alcohols (or at least reducing the amount) can resolve your gastrointestinal discomfort.

Involve Professionals When Needed

You should talk to your doctor about any potential food allergies or sensitivities, especially those that might be serious. However, utilizing the scientific method to run your own dieting experiments can allow you to test different food combinations to maximize your nutrition program, improve gym performance, and generally feel better throughout the course of the day.