In the last ten years, gluten has gotten a lot of attention. It makes sense, especially given the relatively recent increase in reported cases of celiac disease (self-diagnosed or not) as well as disorders like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and Crohn’s disease.

Nowadays, choosing a gluten-free style of eating is much more common, with many people participating for reasons other than simply to treat celiac disease. As with any rising dietary trend, it’s important to understand the basic underlying principles. Let’s take a look at gluten and see if we can understand what’s going on.

What is Gluten?

Gluten is a grain-based protein found in wheat, rye, and barley. As a component of processed foods, gluten can be found in bread, pasta, cereals, pizza, beer, cookies, and others. There it functions literally as a glue to give foods their structure (e.g. breads) and consistency (e.g. pasta).

It can also be found in less-obvious foods like soy sauce, ketchup, ice cream, and even hygiene products like shampoo or lotion. I don’t know about you, but it’s super strange to think of an ingredient like gluten, something of which I have eaten my fair share, contained in a form that I would never in a million years associate with food.

Gluten is made up of the smaller protein fractions gliadin and glutelin. Of these two, gliadin is the one that seems to cause the most problems. For those with celiac disease (and gluten-sensitive people alike), it is most certainly an unwelcome party-crasher.

Celiac Disease

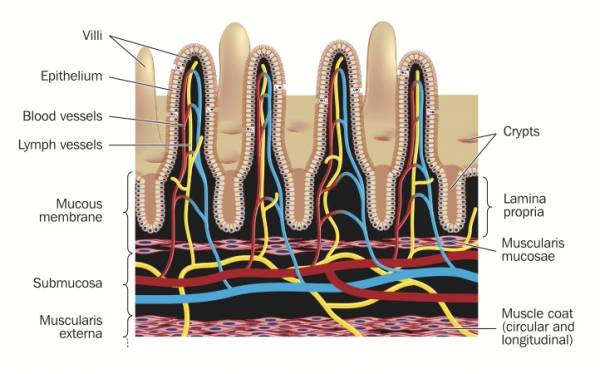

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease characterized by damage to the digestive system, specifically the hair-like villi cells that form the absorptive and protective lining of our small intestine. These cells become degraded and lose their ability to absorb nutrients. They also lose their ability to protect the inside of the body (the bloodstream and internal organs) from outside allergens or toxins routinely present in the food we eat.

As surprising as it may sound, our digestive system is considered to be outside our body. In other words, the cells lining our digestive tract, from mouth to anus, separate the food we eat from our insides. Normally, these cells are absolute rock stars and, in a perfect world, do a top-notch job of keeping bad stuff like bacteria and other environmental toxins out of our system while letting in the good stuff such as proteins, amino acids, and sugars. However, in cases like celiac disease, this picture-perfect scenario ceases to exist.

What Does Celiac Disease Look Like?

Celiac disease is no joke. This not-so-awesome immune response to gluten can manifest itself in many ways, from the more obvious diarrhea, abdominal pain, cramping, and chronic fatigue, to less-conspicuous changes in the joints or even the brain. Individuals with undiagnosed celiac disease can often appear malnourished or emaciated, but not all do, and not all individuals show the most characteristic symptoms.

Unfortunately, in addition to an increase in the numbers of reported celiac disease, there are many more people affected by a wide spectrum of gluten-sensitivity disorders. As misfortune would have it, the culprit seems primarily to be gliadin. It does a fantastic job of mucking up the body’s intestinal security.

Gliadin Affects Intestinal Permeability

The effects of gliadin on the function of the intestinal tract are seen in both those individuals with celiac disease and those without. As gliadin passes into the intestines, it is detected by epithelial cells lining the intestinal wall. In response, a substance called zonulin is released, which affects the function of cellular gateways, known as tight junctions, that sit in between the epithelial cells. To illustrate this, think of a tight junction as a gated alleyway between two buildings. Ordinarily the gate is locked and requires a key to open. Certain molecules have the correct key and are allowed to pass through into the alleyway.

The effects of gliadin on the function of the intestinal tract are seen in both those individuals with celiac disease and those without. As gliadin passes into the intestines, it is detected by epithelial cells lining the intestinal wall. In response, a substance called zonulin is released, which affects the function of cellular gateways, known as tight junctions, that sit in between the epithelial cells. To illustrate this, think of a tight junction as a gated alleyway between two buildings. Ordinarily the gate is locked and requires a key to open. Certain molecules have the correct key and are allowed to pass through into the alleyway.

Unfortunately, the same is true for gliadin. By stimulating our friend zonulin, it can open and pass through the gate. To make matters worse, individuals with celiac disease release significantly more zonulin, causing their tight junctions to remain open for a longer period of time. This allows greater opportunity for toxins, bacteria, and other outside substances to sneak their way through the intestinal lining where normally they would be prohibited.

“Leaky Gut”

This increased access to outside substances is often referred to as “leaky gut.” Although somewhat vague, this description still does a pretty good job of illustrating why there is oftentimes a prolonged condition of inflammation experienced by those with some form of gluten sensitivity.

To put it in perspective, people with celiac disease have a genetic predisposition towards gluten sensitivity. That’s why they have celiac. However, there are also tons of people out there who have some form of gluten sensitivity without an official diagnosis of celiac disease (i.e. they don’t have the genes causing the telltale immune response to gluten).

This prolonged autoimmune response of celiac disease, as well as chronic low-grade inflammation seen in non-celiacs can very likely contribute to the development of diabetes, heart disease, and even neurological disorders. Let’s be honest, that may be the most frightening part of having a “leaky gut.” Sustaining damage to the digestive system is bad enough, but then add the very likely potential of affecting other organs like the heart and brain and we’re talking SCARY.

So, Gluten-Free or No?

This brings up the question, “Is it best to avoid gluten in all shapes and forms?” I’m sure many of you reading this will answer with a resounding “Yes!” and I’m tempted to agree (albeit with a bit of well-meaning hesitation).

Even though many of us (myself included) experience no overt symptoms to consuming gluten, it doesn’t mean we aren’t experiencing some inflammatory response. It most likely means our immune systems are able to handle the situation and so it goes unnoticed. However, it is difficult to argue with recent research (check out the references below) that has demonstrated an increase in intestinal permeability, varying in magnitude though it may be, in both celiacs and non-celiacs when exposed to gluten.

Even though many of us (myself included) experience no overt symptoms to consuming gluten, it doesn’t mean we aren’t experiencing some inflammatory response. It most likely means our immune systems are able to handle the situation and so it goes unnoticed. However, it is difficult to argue with recent research (check out the references below) that has demonstrated an increase in intestinal permeability, varying in magnitude though it may be, in both celiacs and non-celiacs when exposed to gluten.

At the same time, it’s worth considering the anecdotal accounts of many individuals who have tried removing gluten from their diets and noticed a significant improvement in symptoms. All in all, it seems sensible to say that, for those of us who have never consciously attempted to go without gluten it may be worth our time and energy to try it out and see what happens.

References:

1. Zonulin and Its Regulation of Intestinal Barrier Function: The Biological Door to Inflammation, Autoimmunity, and Cancer. Available at: http://physrev.physiology.org/content/91/1/151.long.

2. Fasano A. Leaky Gut and Autoimmune Diseases. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 2011;42(1):71–78.

3. Zonulin, regulation of tight junctions, and autoimmune diseases – Fasano – 2012 – Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences – Wiley Online Library. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.liboff.ohsu.edu/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06538.x/pdf.

5. Tight Junctions, Intestinal Permeability, and Autoimmunity Celiac Disease and Type 1 Diabetes Paradigms. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2886850/.

6. RHR: Pioneering Researcher Alessio Fasano M.D. on Gluten, Autoimmunity & Leaky Gut. Chris Kresser. Available at: http://chriskresser.com/pioneering-researcher-alessio-fasano-m-d-on-gluten-autoimmunity-leaky-gut.

7. Gliadin induces an increase in intestinal p… [Gastroenterology. 2008] – PubMed – NCBI. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18485912.

8. Gliadin, zonulin and gut permeability- Effects on celiac and non-celiac intestinal mucosa and intestinal cell lines, Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, April 2006.pdf.

9. Early effects of gliadin on enterocyte intracellular sig… [Gut. 2003] – PubMed – NCBI. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12524403.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.