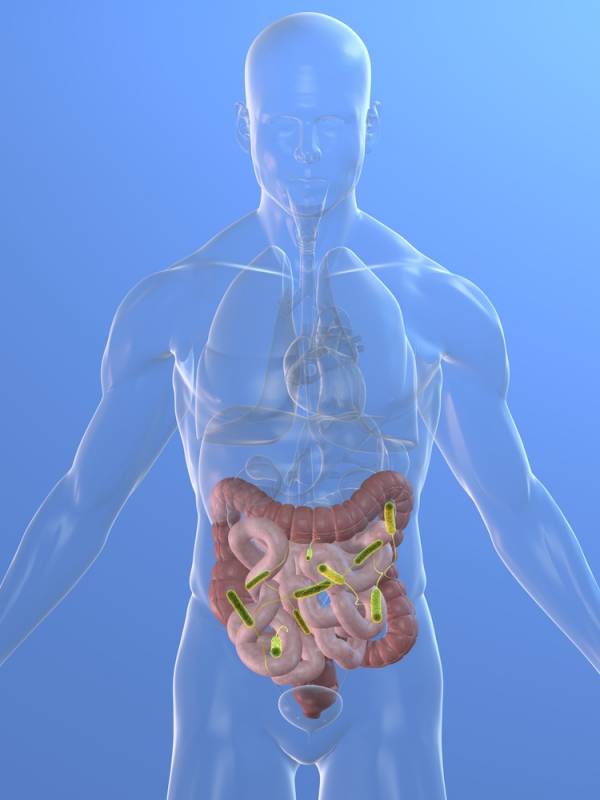

Last week I talked about the potential link between gut bacteria and obesity. There was a great response to the article, and one of the comments was a question asking how we assess whether or not our gut bacteria are healthy. I was intrigued, and wanted to find an answer, so I did a little bit of research.

Turns out, there are a few different methods in use by health professionals to assess the nature of our bacterial microflora. These are often used to assess whether or not an individual is suffering from a bacterial imbalance, such as the case with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).1 Some methods have better results than others, so let’s look into a few of them.

Hydrogen Breath Test

The hydrogen breath test is a way of measuring the amount of hydrogen present in our breath when we breathe out. Keep in mind, hydrogen shouldn’t normally be in our breath, and this test operates on the assumption that the only hydrogen present is from the metabolism of carbohydrates by bacteria.2 To perform this test, a person consumes various types of carbohydrates such as glucose, lactulose, and fructose, which are metabolized by bacteria in the mouth and, in the case of SIBO, in the small intestine. Fermentation (i.e. the process by which bacteria break down carbohydrates and sugars) releases hydrogen as a byproduct, which is passed into our respiratory system, breathed out, and measured.3

How accurate is it? Unfortunately, there are a few things that can affect the accuracy of the hydrogen breath test. First, not all bacteria in the body produce hydrogen, in which case they would be missed by the test. Second, disorders of carbohydrate metabolism such as celiac disease, can produce false positives. Bacteria in the mouth may also throw off the results. Having a digestive system that moves too slowly, such as food that takes a bit longer to empty from the stomach, can also contribute to inaccurate readings.2

Bacterial Culture of the Small Intestine

Obtaining a sample of bacteria from fluid in the small intestine is considered the “gold standard” of diagnostic tests. This is because the presence of bacteria in the small intestine is a compelling sign of gut bacteria imbalance and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. However, despite its reputation, research has been mixed when it comes to the accuracy of bacterial cultures.4

This procedure, known as an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, or EGD, is performed by passing a long, flexible tube with a camera (an endoscope) through the mouth, esophagus, stomach, and into the small intestine. If you can picture this, great. If not, let me describe it in a little more detail.

This procedure, known as an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, or EGD, is performed by passing a long, flexible tube with a camera (an endoscope) through the mouth, esophagus, stomach, and into the small intestine. If you can picture this, great. If not, let me describe it in a little more detail.

During my dietetic internship to become a registered dietician, I spent the better part of a year working in various units in a hospital. During one of my stints, I had the esteemed opportunity to observe a day of endoscopic procedures. These included everyone’s favorite – the colonoscopy – and, at the other end of the pipe, the EGD. Sedatives are often used to help people relax during these procedures, and you can imagine why. For the EGD, the endoscope is passed through the mouth, over the tongue and into the oropharynx – around the neighborhood of the gag reflex – and into the esophagus and so on. If it sounds uncomfortable to you, that’s because it is.

The point is that despite bacterial cultures being considered the gold standard when testing for the presence of bacteria, invasive procedures are not something that you’ll see many people lining up for (at least not voluntarily). In other words, they’re not performed very frequently, and the research behind them is inconclusive.5

Taking a Stool Sample

The last type of assessment we’ll look at is the stool sample. While sampling of the bacteria in feces has commonly been used by health professionals and researchers to assess gut microflora, it has some limitations that make it less than ideal for creating an accurate snapshot of the bacterial makeup of the gut.6

One reason is that feces only contain a fraction of the millions of types of bacteria present in the gut. More importantly, feces consist predominantly of bacteria from the colon and rectum. Bacteria further upstream in the stomach and small intestine are not generally accounted for in the feces. Therefore, if a stool sample only represents a fraction of the total makeup of a person’s gut bacteria, it’s challenging to fashion a clear assessment of overall balance, good or bad.

Final Thoughts

Other than the hydrogen breath test, these methods are generally inaccessible or unrealistic for most people unless there’s something more serious at work. So if none of these are realistic options, what can you do? What’s available?

Other than the hydrogen breath test, these methods are generally inaccessible or unrealistic for most people unless there’s something more serious at work. So if none of these are realistic options, what can you do? What’s available?

In my opinion, taking stock of your diet is the first step. Of course, if you are struggling with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn’s, or some other gastrointestinal condition, it’s prudent to consult your physician. But also take a good, hard look at your diet. Is it imbalanced? Is it overly inflammatory? Does it make you feel like crap?

Be mindful of foods that bother you. Try eliminating refined sugars and other processed and highly inflammatory foods and see if there’s a change. Take a stab at paleo or even a modified primal diet. And if you’re more proactive, taking a probiotic supplement or increasing your intake of fermented foods can potentially be a very beneficial step in the right direction.

Stay tuned for next time, when I’ll be addressing probiotics and their role in reestablishing balance to the microflora of the gut.

References:

1. Dukowicz AC, Lacy BE, Levine GM. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2007;3(2):112–122.

2. Simrén M, Stotzer P. Use and abuse of hydrogen breath tests. Gut. 2006;55(3):297–303.

3. Gasbarrini A, Corazza GR, Gasbarrini G, et al. Methodology and indications of H2-breath testing in gastrointestinal diseases: the Rome Consensus Conference. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;29 Suppl 1:1–49.

4. Khoshini R, Dai SC, Lezcano S, Pimentel M. A systematic review of diagnostic tests for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2008;53(6):1443–1454.

5. Kerckhoffs APM, Visser MR, Samsom M, et al. Critical Evaluation of Diagnosing Bacterial Overgrowth in the Proximal Small Intestine. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2008;42(10):1095–1102.

6. Zoetendal EG, Cheng B, Koike S, Mackie RI. Molecular microbial ecology of the gastrointestinal tract: from phylogeny to function. Current issues in intestinal microbiology. 2004;5(2):31–48.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.