The following is a guest post from Sarah Bolandi of Bumfuzzled Jane:

While created in the late 1800s, artificial sweeteners seem to have overtaken food products in recent years. Food producers substitute sugar in everything from coffee to ketchup, significantly assisting people in a sugar-free lifestyle. However, as with any product, concerns of artificial sweeteners’ long-term side effects are being examined. If you’re one of the billions who consume these products there are some serious items to consider before chugging another soda. While some data is yet incomplete, the research that has been conducted may serve as projections for what to expect in years to come.

Currently, there are four main sweeteners dominating the market. Each sweetener contains a different ingredient, different color packaging, and has different affects. Therefore, examining them individually only seems fair.

Saccharin aka Sweet’N Low (pink packet)

As the most popular artificial sweetener worldwide, much debate has arisen from this infamous product. In the 1970s, the FDA originally banned saccharin because of animal studies conducted showing bladder cancer in male rats.1 However, when the ingredient was studied on mice, monkeys, and hamsters, there was no consistent evidence that it would increase bladder cancer in humans, even at the highest levels of consumption.2

Aspartame aka Equal (blue packet)

Second to saccharin, aspartame is the most used artificial sweetener in the world (Soffritti et al. 2005). Since it’s approval by the FDA in 1974, it can now be found in over 6,000 products and represents 62% of the value in the global sweetener market.

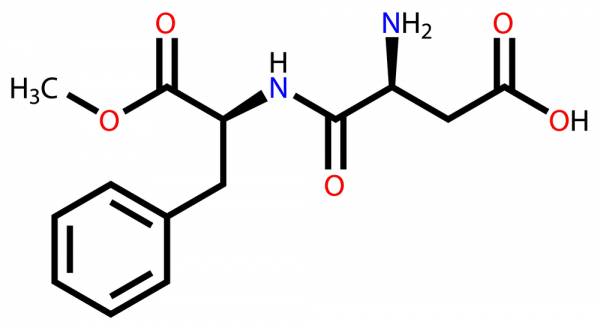

When consumed, aspartame is absorbed into the gastrointestinal tract in three forms: aspartic acid, phenylalanine, and methanol.3 I know, what does that mean for my innards? Aspartic acid and phenylalanine are amino acids, two of the twenty amino acids that make up proteins. Methanol is also no stranger to humans in that it can be found in fruits and veggies. When broken down in digestion, it is metabolized first to formaldehyde, then formic acid, and finally to water and carbon dioxide.4 While methanol has been rumored to cause health concerns like headaches or blindness, the levels in our sweeteners are too low for this to occur.

The only serious, long-term affect that has been discovered is the consumption of aspartame in people with phenylketonuria (PKU). PKU is a rare disorder where the individual is unable to metabolize phenylalanine. The discovery of PKU is detected at birth through a mandatory screening program so those who have it are likely aware of it.5

Sucralose aka Splenda(yellow packet)

Approved by the FDA in 1998, sucralose became known as a “second-generation sweetener.”6 Sucralose is made with dextrose and maltodextrin, which adds the bulk required to measure it like sugar. While sucralose is stable at high temperatures, there have been concerns that the breakdown of its ingredients may be toxic to humans. However, in an article by Caroline Sham from 2005, the author stated “In an acidic environment, sucralose will hydrolyze into two chlorinated monosaccharides…but there is no evidence that sucralose or any of its breakdown products dechlorinate in any species and therefore are stable in the human body.”

Stevia aka Stevia in the Raw (green packet)

According to their website Stevia in the Raw is a low-calorie, gluten-free sweetener made from the “sweet leaves of the stevia plant.” Stevia has over 180 species but only stevia rebaudiana yields the sweetest taste that equates to over three hundred times sweeter than sucrose.7 Because so little is known about this product, researchers studied its effects on the body of diabetic and hypersensitive patients. While changes were found in “blood sugar levels, insulin level, blood pressure, urine sodium excretion, lipid profile and weight of the subject,” nothing was significant enough to draw statistics on.8

These sweeteners were created to substitute sugar, which used to be a household staple. But like anything else, we abused our consumption and now sugar is scary and has helped lead to the obesity epidemic. Now the only time sugar gets any real hype is during the holidays and at Paula Deen’s house.

So if we want to avoid sugar, many of us are left with the dilemma of figuring out how bad artificial sweeteners really are for us, while simultaneously using them. In the research conducted on laboratory animals, the levels of sweeteners they were fed were extremely large amounts. While we may not be consuming what is equivalent to mass quantities on a daily basis, it is unsure what prolonged consumption might equate to in the future. The safest method would be to consume artificial sweeteners in moderation. I know it’s hard for us not to order seven Splendas at the drive-thru but making the effort could make the difference.

Another consideration is to use natural alternatives to sweeteners. Ingredients like honey, spices, vanilla bean, and agave nectar will add the taste you’re missing. As with anything else though, even these products need full examination on their production before consumption, and may have their own drawbacks, as well. Just because it’s ‘natural’ sugar doesn’t mean it’s not sugar.

Be safe by being informed about what you’re eating. The FDA is there to protect us but even they don’t know the long-term affects we may face.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.

References:

1. Mann, Denise. Are Artificial Sweeteners Safe?

2. Soffritti, M., Belpoggi, F., Esposti, D.D., Lambertini, L., Tibaldi, E., & Rigano, A. First Experimental Demonstration of the Multipotential Carcinogenic Effects of Aspartame Administered in the Feed to Sprague-Dawley Rats. Environmental Health Perspectives. 114 (2005): 379-385. DOI: 10.1289/ehp.8711

3. Health Canada. Aspartame last modified October 14, 2005

4. Sham, Caroline. A Safe and Sweet Alternative to Sugar. Nutrition Bytes. 10 (2005)

5. In the Raw. Stevia in the Raw. accessed October 2012.

6. Savita, S.M., Sheela, K., Sunanda, S., Shankar, A.G., Ramakrishna, P., & Sakey, S. Health Implications of Stevia rebaudiana 15 (2004): 191-194.