“You don’t look strong.”

“He (or she) doesn’t look that strong”

These words and other similar ones have been uttered in my presence much too frequently during my forty-plus ears of involvement in weightlifting. These comments are almost always delivered by people unfamiliar with the sport and their statements are directed at weightlifters.

What these people are inferring is that weightlifters don’t look like bodybuilders. Mass media has convinced them the bodybuilding image is the one that represents physical strength. (That aesthetic standard, by the way, was derived from comic book art.)

The best female lifter I ever coached was Diana Fuhrman. She was a six-time world team member, a four-time national champion, and a many times national record setter with best lifts of 93kg and 116kg at 67.5kg bodyweight. She would always get aggravated when people told her that she didn’t look strong. I told her to tell them that she was strong so she must be what strong looked like.

“People who don’t know any better seem to have a preconceived idea of what bodyweight is appropriate for a young weightlifter[.]”

This advice was based on how we should be determining empirical truths, and not simply accepting some fiction as the guiding standard.

So the Deal With Bodyweight Is…

Unfortunately the same sort of logic is used in dealing with the bodyweights of developing young lifters. People who don’t know any better seem to have a preconceived idea of what bodyweight is appropriate for a young weightlifter without any giving over any thought to how weightlifters grow and develop.

RELATED: The Concept of Balancing Development in Beginning Weightlifters

I’ve seen a thirteen-year-old beginner who was 5’6” (168 cm) and weighed 59kg being encouraged to lose weight before his first meet as there were only two lifters in the 56kg class and he could win a medal there.

If you want an untrained adolescent to develop into a mature weightlifting athlete, the last thing you want to do is encourage him to lose bodyweight from an already too-thin body during the developmental years. All too many fledgling coaches think that because mature athletes shed a few pounds to make weight, then everyone else ought to be doing it as well.

“Young weightlifters should train with a long-term goal of attaining an optimal bodyweight for their mature height without any interruptions.”

Of course this same train of thought can be wrong the other way, as well. During the 1970s when the 152kg Alexeyev was the preeminent lifter on the planet, people would send me fat kids thinking they were doing me a favor by uncovering “talent.”

In This Story, The Short Guy Wins

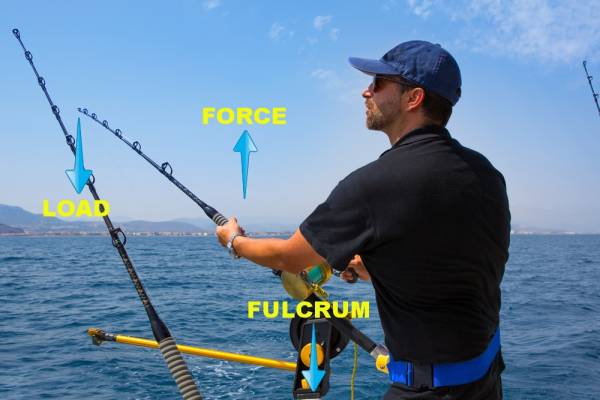

So here’s the reason why a tall guy who weighs 77kg can’t lift as much as a short guy who weighs the same, all other factors being equal.

Look at the figure of the fisherman. To pull up on the pole to overcome the load of the fish, the fisherman grips the pole closer to the load. This shortens the length of the lever and increases the mechanical advantage. If he were to grip it closer to the fulcrum, it would be much more difficult as it would increase the distance between his hand and the load.

RELATED: Weightlifting Will Make You Shorter (and Other Ridiculous Myths)

Tall lifters have longer levers and therefore must exert more force to lift the same weight and even greater force to lift a heavier weight. This can only be accomplished by increasing muscle mass in order to generate more force.

How to Determine a Reasonable Bodyweight Goal

The best thing to do as far as determining a bodyweight goal is to study the data of the bodyweight-to-height ratios of top lifters. While there are occasional exceptions, there is a general trend.

RELATED: An Analysis of Weightlifting Trends

If one were to look at the starting line-ups during the introduction ceremonies of each weight class at a major international event, its fairly obvious there is a certain homogeneity of body types and heights. Certainly there is a fairly limited height range for each bodyweight category.

What you should surmise is that there is a certain optimal bodyweight range for a given height. While an athlete might not be at that bodyweight range early after the mature height is reached, that range should become a goal as the eventual mature, optimal bodyweight.

“The pathway to reaching an appropriate bodyweight will involve eating a great deal of food. “

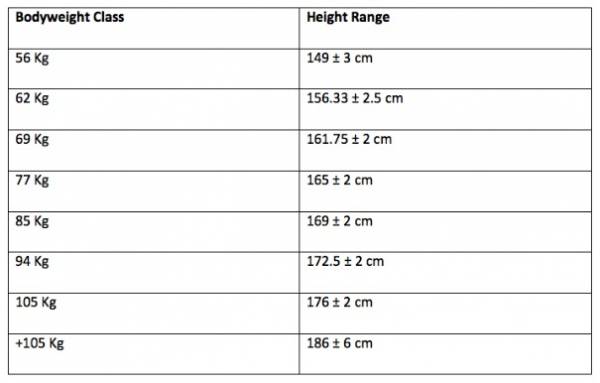

To assist you, the audience, I’m including some data from my book Weightlifting Programming that covers this very topic. The following calculations for ideal height ranges for top international-class male lifters were calculated using linear interpolation of Robert Roman’s data by Shaun LeConte. These figures should be considered guidelines, but I feel they are entirely appropriate.

Height ranges for female lifters were one of the parameters undertaken for Leslie Musser’s master’s thesis. The subjects were the competitors at the 2009 Pan American Weightlifting Championships and the figures should stand as representative ranges for top-level international lifters. The +75kg class was not measured.

The preceding two tables should provide sufficient guidelines for determining bodyweight goals for serious weightlifters.

Eating for Weightlifting

The pathway to reaching an appropriate bodyweight will involve eating a great deal of food. The composition of the diet is a topic best left to another discussion. Smaller lifters may need to consume a minimum of 3,200 calories per day, while larger lifters have been known to consume as many as 9,000 calories per day. These amounts are best consumed through five or six meals per day.

“If you want an untrained adolescent to develop into a mature weightlifting athlete, the last thing you want to do is encourage him to lose bodyweight[.]”

It is when the lifter is close to reaching the mature bodyweight that losing weight for competitions is a consideration. Until that point, the athlete should be most concerned with growth and development.

The mature athlete should be consuming these large amounts of calories in order to maintain a bodyweight slightly above the competitive limit in order to have sufficient reserves to restore from rigorous training. When the time comes for making weight, the omission of a meal or two and appropriate but reasonable water loss should enable the lifter to weigh the designated limit without undue duress.

After the Weigh-In

The rules of weightlifting require that athletes weigh in from two hours before the start of competition to one hour before the start of competition. This provides a narrow window of time during which the athlete can eat, drink, and digest. The quantity and nature of nutrients consumed after the weigh-in are thus of great importance to insure an optimal performance.

RELATED: Cutting Weight In Weightlifting – Is There a Better Way?

Fortunately the clean and jerk is the second lift contested. Thus, there is more time for the athlete to achieve a feeling of fullness that may be lost during the weight-loss process. The feeling of fullness is more helpful for performing the clean and jerk than for the snatch.

The Wrap-up

There are a number of bodyweight issues involved with the sport of weightlifting that must be taken into consideration by young lifters and their coaches. Mature, successful weightlifters weigh considerably more than non-athletes of comparable heights. Young weightlifters should train with a long-term goal of attaining an optimal bodyweight for their mature height without any interruptions.

Hard training, mature weightlifters must consume large daily quantities of calories in order to maintain the appropriate bodyweight to withstand the demands of rigorous training. The omission of one or two meals and some water will result in sufficient weight loss to achieve the bodyweight class limits of competition. Post weigh-in ingestion must be planned in order to compete optimally.

These are not difficult concepts to comprehend, and should serve athletes and coaches as they proceed along the developmental pathway.

Photo 1 and 2 courtesy of Becca Borawski Jenkins.

Photo 3 courtesy of Shutterstock.