If you’ve ever experienced lower back pain, then you know it’s potentially expensive. We miss work, file insurance claims, and seek out countless passive therapies to feel better. On top of that, we end up with gym memberships for which we pay exorbitant fees and don’t use.

So what is lower back pain? Is it always the dreaded, four-letter word “disc”? Or can it be something different? And is it always a bad thing?

Let’s talk about the disc, and then we’ll get on to why you feel what you feel and what to do about it.

Disc Anatomy

The intervertebral disc is comprised of a nucleus and annulus. The nucleus is to the disc what cream filling is to an Oreo (the best part). It is 85% water and has a high concentration of proteoglycans, collagen, and elastin. These properties help the disc to distribute hydraulic pressure across the vertebrae.

The annulus surrounds the nucleus, is made up of 60% water, and has a smaller concentration of proteoglycans, collagen, and elastin. However, the annulus also has chondrocytes and fibroblasts. These comprise the fibrocartilage that protect the disc and further attenuates shock absorption across the nucleus.

As we age, the water and proteoglycan concentration of both the nucleus and the annulus decrease, resulting in decreased nutrition and shock attenuation. Furthermore, there is a component of the vertebrae known as the endplate. This is the interface of the disc and vertebrae at the top and the bottom.

“The time of day that you exercise matters when it comes to having a healthy back and making proper exercise selection.”

Endplates act to contain adjacent discs and provide additional shock attenuation and a semipermeable membrane for further disc nutrition. The endplate degrades with aging, becoming weak and unable to support the disc. Combine that with muscular weakness and poor body mechanics and what do you have? A sick disc.

In addition to failure to support the disc, the endplate changes may also contribute to chemical consequences within the disc, allowing inflammatory factors to enter the disc at a rate that exceeds healing. Meaning, the pain in your back does not have to be mechanical in nature. It is related to chemistry. And how do we treat chemistry? Pharmacologically.

The Origin of Back Pain

So where is this back pain coming from? In a 1991 study, examiners studied the response of stimulation of tissues in 193 patients under local anesthesia. The findings were staggering:

- Sciatica (aka buttock pain that radiates down the posterior thigh and leg) could only be produced by stimulating a swollen, stretched, or compressed nerve root.

- On the contrary, back pain was produced through stimulation of a variety of tissues, most frequently the annulus and posterior longitudinal ligament.

- Pressure at the endplate also resulted in deep, non-specific low back pain.

- Buttock pain was produced through simultaneous stimulation of the annulus and nerve root.

- Finally, stimulation of the facet joint (the joint created by vertebrae sitting on one another) rarely produced any low back pain. If it did, the pain stayed local to the back, never referring to the buttock or leg.

Translation: the source of most low back pain is chemical and occurs primarily in the disc and supporting ligamentous structures. The good news is we have an ability to influence our chemistry and provide more support through strengthening our musculature.

Mobility for a Healthy Low Back

The time of day that you exercise matters when it comes to having a healthy back and making proper exercise selection. Time of day affects the nutrition and water concentration of your discs, thereby improving your chemistry and giving the disc what it so desires.

When you wake in the morning, your disc height and therefore fluid has increased. If you plan on lifting, you are at a slight disadvantage as there is increased pressure on the disc. If you move wrong or move poorly, you place the annulus and endplates at a disadvantage and your lumbar spine is vulnerable. To mitigate this, choose to warm up in a fashion that will help to “dehydrate” your overhydrated disc. Some good examples are standing back bends and supine lower extremity rotation.

Back bends to help alleviate morning disc pressure.

Supine rotations are also a great movement for morning mobility.

Throughout the day, the effect of gravity assists in disc dehydration. If you lift in the evenings, you are also at a slight disadvantage as there is less water and disc nutrition available. Less water and nutrition equals less cushion between the vertebrae and nerve roots. To mitigate the potential for compression and shear forces, lying supine with your knees and feet supported, followed by bending from side to side can assist with “rehydration.”

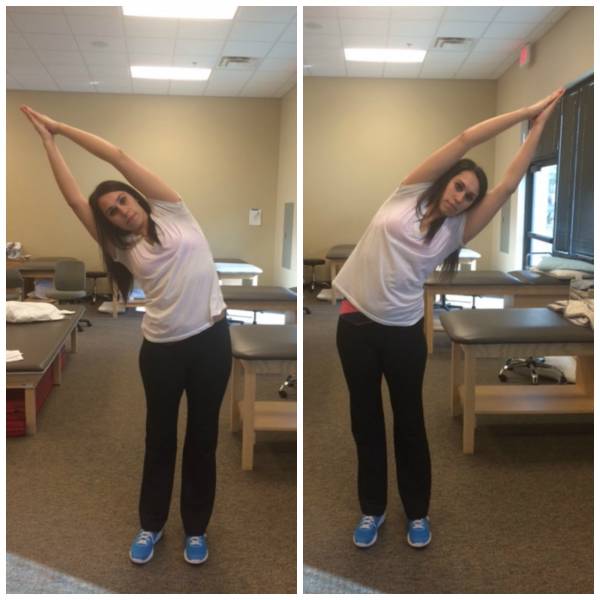

Make side bends a part of your warm up routine if you lift at night.

The Role of the Core

The discs in your spine are vulnerable, fragile, and may often be the problem when it comes to your lower back pain. But that isn’t the end of the world. Many people with lower back pain find relief through physical therapist intervention, chiropractic care, massage therapy, and acupuncture. These are all excellent ways to address your symptoms, but in order to address the source of the problem, it is necessary to alter the way you move.

“In addition to failure to support the disc, the endplate changes may also contribute to chemical consequences within the disc[.]”

There are two muscle groups that play a major role in your lumbar spine health and stability. The transverse abdominis is your deepest abdominal muscle. As it lies beneath the rectus abdominis and external and internal obliques, it runs along the same line of application as a weight belt. But the problem is we often don’t know how to use it. This little muscle attaches posteriorly to the thoracolumbar fascia, which helps to lock down the lumbar spine. It’s a good helper.

Try this to find your transverse abdominis:

- While sitting or standing, place your hands on your hips. Your fingertips should be lying on your abdomen just inside your hipbones.

- Pull your belly button towards your spine, like you are trying to zip up a tight pair of jeans. Don’t hold your breath!

- You should feel little muscles pop up under your fingers. This is your transverse abdominis, and it should be engaged any time you move. Maximal contraction when you lift, 20-30% engagement as you move throughout the day.

The second muscle group to pay attention to is your hip flexors. Your hip flexor group runs superiorly and posteriorly from your femur, across your hip joint, and attaches onto the transverse processes of your lumbar spine. If you think about a string running along the same line, and you tighten it, can you imagine what happens? The tightness in that string pulls the lumbar vertebrae forward, compressing the discs, and decreasing the available space for nerves to pass through.

One of the best ways to mobilize and lengthen your hip flexors is a lunge. You can make the lunge even saucier by reaching your arms overhead, rotating your arms from one side to the next, or rotating your arms across your body. Using your upper extremity as a driver, keeping your pelvis and lower extremity stable, you are asking the more proximal component (attachment at the lumbar spine) to lengthen. If you deepen your lunge, you are asking the more distal component (attachment at femur) to lengthen.

Learning to strengthen and lengthen these muscles in conjunction with the principles of dehydration and rehydration will give your lumbar spine the love it so desperately craves.

References:

1. Kuslich SD1,Ulstrom CL,Michael CJ. “The tissue origin of low back pain and sciatica: a report of pain response to tissue stimulation during operations on the lumbar spine using local anesthesia.” Orthop Clin North Am.1991 Apr;22(2):181-7.

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Check out these related articles: