Speed thrills. Watching an athlete chase down an opponent, or dash away from someone chasing them, is an iconic and exhilarating element of sport around the world. An athlete with acceleration to burn will always raise eyebrows amongst coaches and scouts, and there’s no athlete who doesn’t want to get faster for his or her sport.

Speed thrills. Watching an athlete chase down an opponent, or dash away from someone chasing them, is an iconic and exhilarating element of sport around the world. An athlete with acceleration to burn will always raise eyebrows amongst coaches and scouts, and there’s no athlete who doesn’t want to get faster for his or her sport.

Professional sprinters aren’t the only athletes who could benefit from a faster running speed.

I’ve used the same program for developing faster running speeds in athletes for over fifteen years. The program produces incredible results for any athlete looking for more speed. The specifics of the framework have altered with experience, but the overall framework remains the same.

By following the five steps of this program, the athletes I’ve trained have found an extra gear when they need it. And even if you’re not blessed with good genetics or a long training history, you can too.

The First Gear: Getting Started

We begin with interval training. Luckily for you, the pace starts off slow.

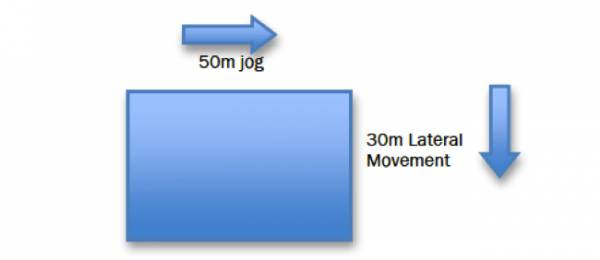

Find yourself a rectangular space of about 30 metres by 50 metres.

- Each lap in your space should consist of two 50 metre jogging sections and two 30 metre side skipping, or lateral movement, sections.

- Jog for the 50 metres section.

- Skip sideways for the 30 metres section.

- Do 4 to 6 laps total.

That’s it. This phase should be done on a day-on, day-off schedule.

When to Go Up a Gear:

Every runner is different and will take his or her own amount of time to adapt to training stressors. If you have a decent training history, it’s likely you can move through this gear quicker than others. Given it’s a low stress session, your progression to the next gear can be as little as four days. If you’re new to running, you’ll need to spend about three months on this phase – and I’m not joking about that. The fibres that make up your tendons and ligaments are made of collagen, and when put under new stress, they take up to three months to adapt and improve enough to handle it.

My general rule is to be able to do this session once, take a day off, then repeat a second time, followed by another day off. If you aren’t in pain or sore, you’ve proven you can tolerate this stress level and can move up a stage.

The Second Gear: Finding Your Tempo

When you’ve decided you’re ready to step up the speed, find an area of about 150 metres in length. In Australia, that’s about the length of an oval football field. The second gear stage uses tempo running: running at a pace that stays consistent from start to finish. There shouldn’t be any significant changes to your running speed throughout the 150 metres.

This phase should feel like you’re running at about 60-70% pace of your maximal speed. If you don’t know what that means for you, here’s a simple way to think of it: if you feel like you’re jogging, you’re going too slow, and if you feel like you’re sprinting, you’re going too fast.

- Run at a tempo for 150 metres. Rest for 30 seconds. Repeat 4 times.

- Rest for 2 to 3 minutes.

- Repeat another 4 tempo runs of 150 metres with another 30 seconds of rest.

- Rest again for 2 to 3 minutes.

You can stop here, or continue on for another four tempo runs of 150 metres with 30 seconds recovery in between each one. Twelve tempo runs for this session is the absolute maximum. This stage is intended to be done on a day-on, day-off schedule, but you can do cyclic aerobic training and strength training on your day off if you wish.

When to Go Up a Gear:

This phase doesn’t need as long an adaptation period for new runners, providing you’ve taken the right amount of time to build your running base up in the first stage. If you do 12 repetitions of the 150 metres tempo run and you don’t feel sore the next day, take a non-running day as per the day-on, day- off schedule, then repeat the session again to make sure the lack of soreness isn’t a fluke.

The progressively higher impact forces at work on this program can take time to build up on your tendons and joints, which is why soreness might be delayed. If the soreness isn’t a fluke, this phase’s duration can be as little as four days. If it is, continue along the schedule until the soreness isn’t an issue before moving ahead to the third gear of the program.

The Third Gear: Ramping It Up

This phase is designed to step your pace up to about 75-85% of your maximal speed, moving you out of a “running” gait pattern and into more of a sprinting pattern. Here, you stick to the day-on, day-off schedule with a maximum of 3 running days per week.

These sessions will see you step up to a total of twenty-four runs of 100 metres each in length.

- Find a space of around 100 metres in length.

- Place a marker at the start, the 40 metres point, the 60 metres point, and the 100 metres point.

- This creates three zones – the first is 40 metres, the second is 20 metres, and the final is 40 metres. We’ll call them the acceleration zone, the holding-speed zone, and the deceleration zone.

- From a standing start, accelerate gradually through the first 40 metres.

- Stop accelerating and hold the speed for 20 metres.

- Gradually decelerate over the last 40 metres until you come to a complete stop by the final marker.

- Take 30 seconds to recover.

- Repeat this acceleration-hold-deceleration run 6 times.

- Take 3 minutes of full rest.

Let’s call this set of splits the (40-20-40) x 6.

From here, in the same session, you adjust the markers to change the length acceleration-hold-deceleration zones as follows:

- (40-30-30) x 6

- (30-40-30) x 6

- (30-40-20) x 6

That’s twenty-four runs in total. Use the same recovery and rest protocol. Take 30 seconds recovery after each run and a full 3 minutes of rest after each batch of 6 runs.

Record your time splits through the zones by having a friend or training partner time you. Alternatively, carry a stopwatch as you run, starting and stopping as you pass the markers of the middle zone. This is important, as progression from this phase depends on your ability to stay within a recommended time range for the middle zone for each split.

The recommended ranges for each zone are below.

- 20 metres zone – range of -/+ 0.5 seconds between each split

- 30 metres zone – range of -/+ 0.75 seconds between each split

- 40 metres zone – range of -/+ 1 second between each split

This time range is the margin of error allowed between splits. For example, if you run the 20 metre zone in 3 seconds in one split, then 3.6 seconds in the next, you’re out of the recommended range by 0.1 seconds. These recommended ranges are to make sure you’re not overdoing it and to give an indication of when you can progress to the next phase.

When to Go Up a Gear:

If one of your run split times falls outside of the recommended range for that middle zone, be careful. You get one more run to be able to bring your time back down. If you fall outside the range twice, your session is over.

It’s typical for most runners to have completed all twenty-four runs in this session within one to two weeks. If you find you get to twelve runs and you can’t keep your speed up for your usual middle zone range, that’s perfectly fine. Hold to the day-on, day-off approach and repeat the session until you can do all twenty-four runs within your timed range for the middle zone.

Continue to Page 2 for the Fourth and Fifth Gears in the System

There isn’t an athlete out there who doesn’t want to get faster. This program will get you there.

The Fourth Gear: Time to Get After It

The fourth phase is nearly identical to the third, except now you try to approach a speed above 85% of your maximum speed. If you’re unsure of your maximum speed, aim to drop 0.5 seconds from each of your split times from the last phase as a rough guide.

When to Go Up a Gear:

You’re now fully in a sprinting pattern but not completely putting your foot down. At this level of speed and subsequent stress to your body, change the frequency to a one-day-on, two-days-off approach. As for the previous phase, you stay in this phase if you can’t complete twenty-four runs whilst staying within your timed range for the middle zone in the interval. You can keep your cyclic aerobic and strength training going if applicable on your days off.

The Fifth Gear: Flooring It and Braking Hard

In this final bout of speed training, I recommend using a similar approach of acceleration-hold-deceleration. It’s this pattern that carries over well to sport, with deceleration mechanics coming into play.

You’ll only need a space of up to 70 metres maximum. You will use a similar session outlay as in the third and fourth steps, with the same recovery and rest protocol, but with the following changes in distances:

- (20m-30m-20m) x 6

- (10m-30m-10m) x 6

- (5m-20m-5m) x 6

- (10m-40m-10m) x 6

You’ll see that the middle zone is similar to before and between 20 to 40 metres. Take your best time for each of the 20 to 40 metre zones from the fourth stage and use it as a target range for this final phase. You will have completed this phase if you can stay within 0.2 seconds of your best time for each zone on each run.

Cycle Through the Gears

It’s common for athletes to plateau with extended speed training. This means your nervous system needs a rest. If you find yourself losing speed or unable to complete a phase as recommended in the final stage, drop back two stages for one week, then move up to the next phase for the next week until you return to the stage your were previously struggling with. Use a cyclic approach to balance your stimulus and recovery and get the most out of this program.

I’ve used this simple repeat sprinting program for many athletes for years, with only a few subtle variations as required. Its progressive nature has proved very forgiving for athletes in pre-season training and returning from injury. Whilst the program is clearly challenging, most of my guys who’ve done it have told me that they don’t feel like they’re doing enough.

I recall one Australian footballer telling me he was concerned that when he returned to the main squad for the season he would be undertrained. He needn’t have worried. He ran far quicker and longer than others who had done infinitely more volume at God-knows-what intensity. I’ve used it for my own development and had no trouble going from a football season to a half marathon without no specific training. Trust this program. It works.

More Like This:

- Move Really Quickly: Short Sprints for Long Term Awesomeness

- It’s the 23 Hours a Day You’re Not Running That Count

- Become a Lion: Build Your Aerobic System

- New on Breaking Muscle

Photo 1 courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 2 courtesy of CrossFit.