It’s all patterns. Learning to squat is learning a pattern of movement. As a coach, you see patterns in people too in their behavior and their responses. Different people will give the same reasons as to why they haven’t been able to learn to squat.

It repeats itself in entirely different types of people. They feel off-balance every time they try to squat. They feel like their hips, knees, and ankles lock up on them when they reach a certain depth, keeping them from going any lower.

It’s all patterns. Learning to squat is learning a pattern of movement. As a coach, you see patterns in people too in their behavior and their responses. Different people will give the same reasons as to why they haven’t been able to learn to squat.

It repeats itself in entirely different types of people. They feel off-balance every time they try to squat. They feel like their hips, knees, and ankles lock up on them when they reach a certain depth, keeping them from going any lower.

If a person has never been able to squat correctly, they usually credit it to some particular tight part of their body or specific instance in their life that may have caused this limitation. They may have sprained their ankles too many times playing volleyball as a kid. Their ankle range of motion is now inferior because of this.

Their hips are too tight to squat from lifestyle. The reason is always because of specific particularities. In terms of the parts, it’s difficult to see how the whole of the system needs to be adjusted and manipulated to work in balance, unity, and fluidity to allow for healthy free movement.

Five Main Principles

When I teach beginners that are new to my gym how to squat and deadlift, I teach them five main principles:

- Foot placement/pressure

- Balance

- Alignment

- Breathing

- Bracing

I’ve taught a lot of people how to squat, and it took a long time to learn how to communicate what I wanted them to do. Over time, I found that cues and explanations don’t work unless you could find a way to make them feel what you were trying to explain. The principle of movement that I use to teach someone to squat is a tool to do just that.

If someone has difficulty learning to squat, I’ll never draw attention to focusing on muscle groups, body parts or joint segments. Instead, I’ll use these tools to focus their attention on the feeling of a good squat.

There are so many instances of people with seemingly tight calves or ankles who can miraculously squat when taught to keep correct points of pressure and balance on the feet. For untrained individuals, feelings of mobility restrictions and tightness in the body may be simply because the body isn’t adequately braced, tension isn’t distributed properly, or the body feels imbalanced as the center of mass descends into a squat.

Put very simply, the body improperly tenses and flexes against itself to prevent injury or falling. Whether an injury would occur is irrelevant. If the body feels like it will lose balance or be vulnerable under a load, it will lock up to protect itself. This is part of the feeling of getting stuck while trying to squat down.

If someone was to focus on mobility of a particular muscle or joint, there’s still no guarantee they would be able to squat. But if you teach this person how to create balance in the body and brace the spine so it keeps its integrity under load, the body will unstiffen and allow for better movement.

The true range of motion restrictions does exist and need to be addressed individually. But in untrained individuals, it’s hard to tell what is a true limitation until they learn to move fluently. So. let’s go over the principles.

1. Foot Placement/Pressure

When a beginner learns to squat, it’s crucial they understand that although they should have the capacity to squat with their toes straight, flaring the toes out will help them create better foot pressure and more total contribution of the lower body musculature.

After the feet are set to a comfortable width, tension against the floor has to be created to not only keep balance but also make sure the knees track over the toes correctly. The idea is to think about pushing through the first and second toe and the outside of the ankle at the same time. These two points of contact will usually make the arches of the feet lift up and ground the lifter solidly.

2. Balance

Anyone who was taught to squat with poor instruction, and still has issues reaching depth with proper mechanics, was probably told that they should keep their weight in their heels. The problem with this instruction for a beginner is that they almost always interpret it as putting all of their weight on the back of their heels. The body wants balance, and this means staying over the center of gravity.

Another way of thinking bout this is to try to keep balance over the midline of the body. The body weight should instead be centered over the front of the heel, or the front of your shin if that makes more sense, even before descending into the squat—and especially during the reversal from down to up.

Keeping the balance over the mid-foot will keep the body from folding over or shifting the balance from front to back while squatting. This will allow for proper alignment and mechanics and keep the body from fighting against unnecessary forces and stresses.

3. Alignment

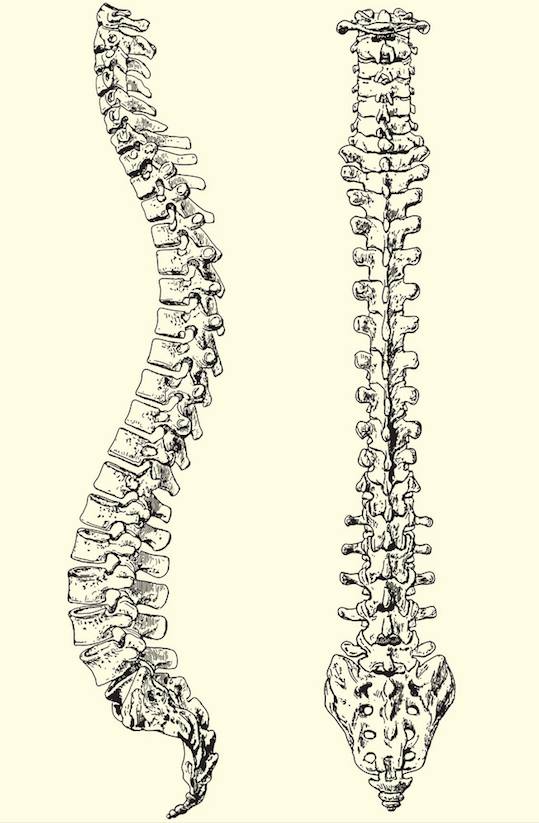

There is a natural curvature of the spine. The lower back arches in, the mid-back protrudes out, and the neck area arches in again. So there should be some extension in the back when you go to squat.

That being said, an exaggerated extension of the lower back is unneeded, counterproductive, and sometimes harmful. When the lower back is in this position, the butt pops out, tilting the pelvis in a way that puts it out of alignment. It’s an easy fix though, squeeze your butt and your pelvis sets under you in a more neutral position.

4. Breathe

An entire series of articles would be the only way to satisfactorily cover how you should use the breath to brace the trunk and lock the spine and pelvis in place while squatting. But I’ll stress the importance of taking the time to educate yourself about this for now.

The best way to start learning how to use the breath in lifting is to stand tall and grab your sides, pressing your fingers into the sides of your belly and your thumbs into your lower back. Take a six-second to inhale, forcing the air down into the lower portion of your torso.

Try to make this breath as deep, slow, and controlled enough to expand not only your stomach but your sides and even your lower back so that the breathing itself forces your fingers out of where they were pressing. Hold it for a two count, then repeat.

5. Brace

Learning the breath is the first and most significant part of learning how to brace the trunk. The breath itself acts as almost an internal corset, locking the spine and midsection.

Once you’ve taken in the breath and held it, tense your entire midsection as you’d imagine you would if someone was about to punch you there. You should feel pleasant and stable and solid at this point. This is bracing.

Start with Feedback

When teaching a beginner, I never show them a bodyweight squat. If it’s been years since someone has tried to squat, they need to start with a slightly loaded variation. A small kettlebell or dumbbell held up in front, as in a goblet squat, is all it takes.

The load provides the person with enough counterbalance and enough feedback to keep and learn correct balance, posture, and straight linear movement. It keeps the lifter upright and almost immediately gives them the feeling of the proper knee tracking and downward sitting of the pelvis between the feet.

Focusing on the principles and using a light load in a goblet squat allows for, in my experience, 90% of people to be able to perform a great squat to depth even if after years without doing it.

If you want a more detailed explanation how to practice these principles of movement and how to put it together while fixing the common faults of back squatting with a barbell, sign up for my newsletter and I’ll send free access to my instructional video directly to your email.

Jesse competes in the sport of Olympic weightlifting, and he was also formerly a competitive powerlifter. He was featured in main strength and fitness publications. You can read more of his work on his website.