Last week, I took a look at various aspects of the rare Triple Crown champions in weightlifting. This week, I’m going to take a look at their counterparts in another sport – boxing.

Last week, I took a look at various aspects of the rare Triple Crown champions in weightlifting. This week, I’m going to take a look at their counterparts in another sport – boxing.

Boxing has a far larger number of champions than weightlifting who have won crowns in multiple weight divisions (boxing calls them “divisions,” weightlifting calls them “categories”). Roberto Duran has won in five different divisions. While still indicative of considerable merit, this boxing situation is problematic.

Roberto Duran

The Beginning: Eight Divisions and One Control Body

Traditionally, boxing had eight weight divisions, ranging from flyweight to heavyweight. In the early 1960s, a junior middleweight division was created halfway between the welterweight and middleweight limits.

This was thought necessary due to the large increment between the two categories (147 to 160 pounds). Soon after, it was decided the welterweights should have a junior division as well, for their increment was nearly as large (135 to 147 pounds).

RELATED: Five Rules for Success in Fighting (And Life)

From the 1950s into the early 1960s, there was only one recognized boxing control body, the National Boxing Association (NBA), which later became the World Boxing Association (WBA).

Occasionally, the New York Boxing Commission would recognize a different champion, but usually pressure would be brought to bear to unify the disputed titles.

A Divided History: Multiple Claims to the Title

But the mid-1960s were a time when, apart from the odd interesting fighter such as Muhammad Ali, the public in general was losing interest in the fight game.

At the same time, other sports, like football and basketball, were gaining in popularity. Soon the initials “NBA” would represent something other than boxing to most of the sporting public.

“These regulating bodies increased the number of weight divisions. Where there once were eight divisions, there are now seventeen.”

As the 1970s and 1980s decades proceeded, these trends accelerated. The only bouts that gathered much interest were the championship matches. Even bouts between high-ranked contenders garnered little attention.

Boxing promoters had to do something to maintain public interest, so they did two things, in fact:

- They found reasons to break off and form multiple regulating bodies. Every weight division then had multiple boxers with a claim to the title.

- These regulating bodies increased the number of weight divisions. Where there once were eight divisions, there are now seventeen. And no, they did not add these divisions to the top. They split every division in two, just like a modern heavy-duty truck transmission has splitter gears in addition to the regular transmission and range combinations. The purpose of these in-between gears is similar to the in-between divisions in boxing: they allow an easier transition from one level to the next.

But in boxing there is also a more insidious effect. There are even more champions, which allows many more fights to be billed as “title fights.”

Multiply these seventeen weight divisions by three, four, or more governing bodies to produce a bewildering number of so-called world champions (not even considering the lesser titles).

RELATED: How to Prepare for and Win a Fight

What all of this boils down to is that it is far easier to become a triple champion in boxing than it ever was before.

Title unification matches are big drawing cards, but it seems no sooner is a title unified than one of the governing bodies decides that situation is intolerable. So some excuse is found to strip the champion of one of the titles and away we go again.

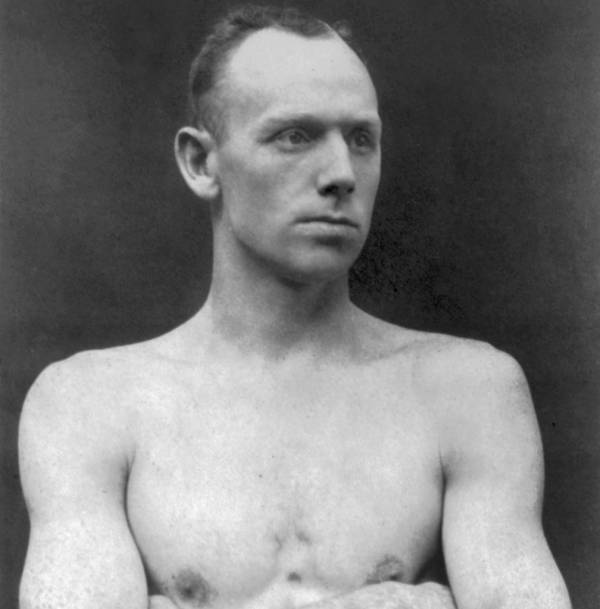

Robert Fitzsimmons: An Unlikely Champion

Going back in history, there are only three fighters who have a legitimate claim to being recognized as true triple champions, a figure equal to that in weightlifting.

The first man to turn the trick was Robert Fitzsimmons back in 1903. “Ruby Robert,” as he was called, won the middleweight title in 1891 and held it for five years, until 1897 when he moved up to defeat “Gentleman” Jim Corbett for the heavyweight title.

Robert Fitzsimmons

In those days there were no divisions in between those two, so Fitzsimmons often fought at a weight disadvantage. He had an unlikely physique, being 5’11” with a powerful set of shoulders developed during his blacksmithing career. But these were set upon a pair of long, skinny legs.

“Amazingly, even when Fitzsimmons fought in the heavyweight division, he never weighed much more than the middleweight limit (160lb).“

Former champ John L. Sullivan described Fitzsimmons as “a fighting machine on stilts.” This is why he was such a good puncher at such a light weight for his height.

Amazingly, even when Fitzsimmons fought in the heavyweight division, he never weighed much more than the middleweight limit (160lb).

RELATED: Making Weight: Why Fighters Cut Weight and 3 Tips for Doing It

Fitzsimmons lost the heavyweight title in 1899 to a much larger James J. Jeffries (6’2″ and 225lb). This did not end the now 36-year-old Fitzsimmon’s career, though. He continued to fight until 1903. In 1903, he won the then newly created light heavyweight title, at the age of forty.

Barney Ross: Junior and Senior Champion

The second triple champion was Barney Ross. In 1933, Ross won the lightweight and junior welterweight titles, both held by Tony Canzoneri. Eleven months later, Ross won the welterweight title.

Barney Ross

Ross’s claim to be a triple champion was not always recognized since one of them was in a junior division. Today, with the proliferation of divisions, he is now generally recognized as a legitimate triple champion.

More importantly everyone recognized him as champion in those days, not just one or two insignificant governing bodies as often happens today. Ross later lost the welter crown and then regained the junior welter one.

RELATED: Why Boxing Is the Toughest Sport

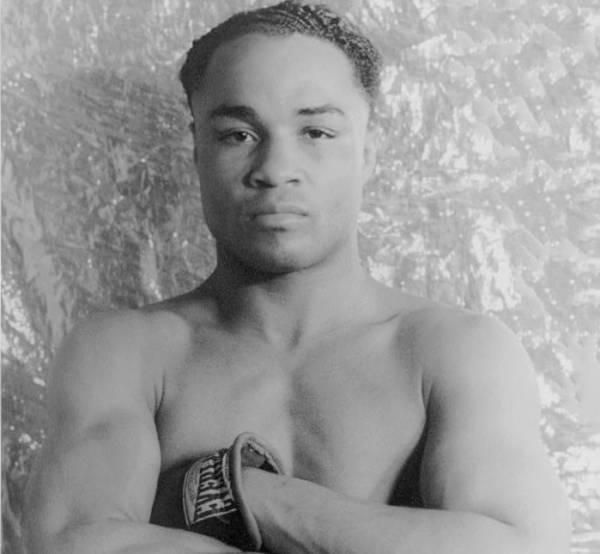

Henry Armstrong: Simultaneous Triple Champion

A few years after that, Henry Armstrong was able to match Fitzsimmons’s record of winning three traditional division titles.

He first won the featherweight title in1937, then decided to challenge for the welterweight crown in 1938, skipping the lightweight division entirely. Once successful there, he decided to fill in the gap, winning the lightweight crown two and a half months later.

“Armstrong held all three simultaneously for a brief period. He eventually did relinquish the featherweight title, but it was because he could no longer make that weight.”

Armstrong later tried to win the middleweight title, but that bout ended in a draw many thought he should have won. Armstrong’s feat tops that of Fitzsimmons for two reasons:

- All three titles were won within a span of ten months.

- None of the titles were relinquished.

Armstrong held all three simultaneously for a brief period. He eventually did relinquish the featherweight title, but it was because he could no longer make that weight.

Henry Armstrong

An Unlikely Progression

It is interesting that all three of these men were able to win their titles after dropping down in weight. This does not happen often in boxing, and even less often in weightlifting.

RELATED: Cutting Weight in Weightlifting: Is There a Better Way?

Athletes in both boxing and weightlifting usually start their careers at a lower body weight than what they end up in. This is due to the fact they must get an early start in life and at that time most people have not reached full adult development.

Conversely, many athletes end up having to fight or lift in a higher weight category at the end of their careers as making weight is ever more difficult. It is unlikely that Ilya Ilyin will win any gold medals at 94kg again.

In any case, it is difficult to win the Triple Crown in either sport, so the select group of such winners will remain small, but also revered over many decades.

Photo 1 by Jim Accordino (Flickr: Roberto Duran 2) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 2 by Unknown [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 3 by Unknown [GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 4 by Carl Van Vechten [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.