This is a rebuttal to Josh Bunch’s article, It’s CrossFit and It’s Going to Hurt:

I’ve read Josh Bunch’s article on CrossFit several times now. What I took away from the article was that there is a real risk of injury when participating in CrossFit and participants or potential participants should be well aware of those risks ahead of time. It is Josh’s opinion that there is a reward from doing CrossFit that outweighs the potential harm. On one hand, he couldn’t be more right. On the other hand, he couldn’t be more wrong.

On one hand, CrossFit is a competitive sport. You may disagree, but if CrossFit isn’t a sport, then neither is Strongman. Regardless, there is a real risk of getting injured while participating in CrossFit. CrossFit competitors are faced with the risk of ruptured tendons, torn muscles, herniated discs, SLAP tears, adrenal fatigue syndrome, overtraining syndrome, and rhabdomyolisis. I can think of a few sports that might result in more devastating injuries, like race car driving (potential death) or MMA fighting (potential brain damage, etc.), but I have a hard time finding a sport that is as unhealthy. I’ve competed in all day wrestling tournaments, half marathons, and strongman competitions. My health has never come close to being as compromised as it has in the days, weeks and months following a CrossFit competition.

With that being said, I don’t have a problem with CrossFit competitors assuming this risk any more than I have a problem with fighters assuming the risk of getting knocked unconscious. I know what it’s like to have a love for a sport. Sometimes the sport you love gives you an internal reward that is so great, you’ll accept the risks that come with it. My love was wrestling. I assumed the risk of contracting mat diseases, cauliflower ear, several concussions, and a separated shoulder because the personal reward was greater than the physical risk. I wasn’t in it for health! As long as the participants are aware of the potential risks, who am I to tell someone not to do CrossFit? So, I agree with Josh that for the avid CrossFit competitor, the reward may be worth the risk.

On the other hand, no one should assume this risk in training, not even competitive CrossFitters. The big problem with CrossFit is not that it is dangerous or that there is a high risk for injury. The problem with CrossFit is that it claims to be both a test of fitness and the fitness program itself. It claims to be both the sport and the strength and conditioning program that prepares you for the sport. CrossFit fails to distinguish between “training” and “testing.”

The only sports that can get away with this without destroying their athletes are sports where success relies heavily on a specific type of accuracy or coordination, like bowling or archery. Here, it’s an advantage to blur the lines of distinction between testing and training. All other sports must distinguish training from testing due to the required restoration processes of training aimed at improving force production. A 100 meter sprinter does not simply run 100 meter time trials for his training program. There is a good reason why athletes train differently than they compete. There’s a difference between building work capacity and testing it.

The only sports that can get away with this without destroying their athletes are sports where success relies heavily on a specific type of accuracy or coordination, like bowling or archery. Here, it’s an advantage to blur the lines of distinction between testing and training. All other sports must distinguish training from testing due to the required restoration processes of training aimed at improving force production. A 100 meter sprinter does not simply run 100 meter time trials for his training program. There is a good reason why athletes train differently than they compete. There’s a difference between building work capacity and testing it.

An exercise program marketed toward the general public that uses tests of fitness as the fitness program itself is unnecessarily dangerous and unhealthy. Contrary to what many believe, it’s also less effective at achieving the desired result, which is improved and sustainable health, fitness. and performance. In his article, Josh stated that results and risk of injury were like a two-sided coin – that you can’t have one without the other. There is some truth to this, but it doesn’t tell the whole story.

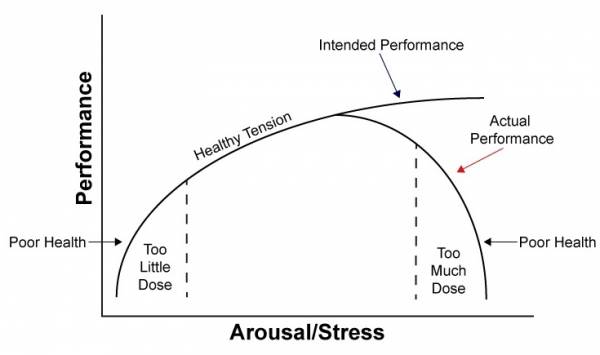

Exercise intensity is like a drug with many potential health and performance benefits. But like all drugs that have potential benefits, more is only better up to a certain point. A better way to look at the relationship between results and risk is to consider the health-performance/stress curve:

On this curve, more arousal or stress is beneficial, at least initially. Stress from exercise can come in the form of volume, frequency, and/or intensity. There comes a point where chasing increased performance by adding more stress starts to backfire. At this point, continued exposure to stress can result in a severe decline in both health and performance. Greg Glassman has said that “nature punishes the specialist.” A more accurate statement is that nature punishes the extremist.

Imagine someone is dehydrated and that it has been determined a prescription of 32 ounces of water over a two-hour period will bring the person back to optimal hydration levels. If he drinks only eight ounces, his condition may improve slightly, but he is still dehydrated. On the other hand, if he drinks two gallons of water as fast as he can, he puts himself at high risk of hyponatremia from overhydration, a potentially fatal disturbance in brain function when someone drinks too much water too quickly. It’s not the volume of two gallons that makes the latter prescription dangerous. It’s the instruction to drink the two gallons “as quickly as possible.” The optimal prescription provides the desired result with little to no risk of hyponatremia because the appropriate dose is consumed at the appropriate rate.

This may not be a perfect analogy, but it illustrates the relationship between exercise intensity and health and performance benefits – too small a dose equals no benefit, while too large a dose equals harm. How much is too much? It depends on the individual. There is no standard volume, frequency or intensity that is too much or too little for all people. But, there is a universal prescription that we can use on any and all people to expose them directly to the dose that is too much. There are two ways to do it:

- Ask someone to do a fixed amount of work as quickly as possible

- Ask someone to do as much work as possible in a fixed amount of time

Look familiar? This is CrossFit. This is overdosing on the drug of exercise intensity and with it comes significantly elevated risk of injury and inevitable adverse health effects. It may not happen overnight, but chasing increased work capacity through max intensity exercise leads to only one place. It’s possible to maximize health and performance benefits, while assuming minimal risk of injury, but not when exercise is turned into a competition. One cannot argue the stress response curve.

Look familiar? This is CrossFit. This is overdosing on the drug of exercise intensity and with it comes significantly elevated risk of injury and inevitable adverse health effects. It may not happen overnight, but chasing increased work capacity through max intensity exercise leads to only one place. It’s possible to maximize health and performance benefits, while assuming minimal risk of injury, but not when exercise is turned into a competition. One cannot argue the stress response curve.

If CrossFit wants to gain the respect of the rest of the fitness industry, or more importantly, keep its adherents safe and healthy, it is going to have to make a distinction between CrossFit the sport and CrossFit the training program. As long as CrossFit workouts are being performed as competitive, scored events in training, the risk of injury and eventual health decline will remain imminent. Changing the CrossFit prescription to make it safer, healthier, and more effective in the long-term is simple, but it’s not easy. The first step is realizing that more isn’t better; better is better. Too much of a good thing, is not a good thing.

Click here to read another rebuttal from CrossFit coach Mike Tromello

Photos provided by Miguel Tapia Images and CrossFit LA.