I’m on to you. You’re not here to read. You’re here to improve. You want to train better, perform better, feel better – whatever your better may be. You are willing to suffer through this article hoping to add just a little bit more knowledge to help you achieve your better. You are also smart enough to know there are no quick fixes or shortcuts, so you’re willing to work. Hard. But in spite of your impressive dedication and awe-inspiring work ethic, you still want better as fast as possible.

Since I know your secret, I’m going to let you in on one of mine. I want to tell you the one thing I see over and over again. The one difference between good performance and maximizing performance potential. The one thing that can be the difference between staying healthy and getting injured. And because you are so smart, you ask, “Why should I listen to you?”

Here’s what you need to know: I am a physical therapist who works almost exclusively with athletes. From lacrosse players to CrossFit, from recreational to the very elite, these are the individuals with whom I work day in and day out. I left the humdrum world of ultrasounds, icepacks, and ankle-cuff weights to work with the most motivated clients and best teachers – athletes. All day every day I work one-on-one with athletes watching them move and problem solve their way (back) to 100%. And over and over again I see a common thread limiting my athletes, their Achilles heel – the hip.

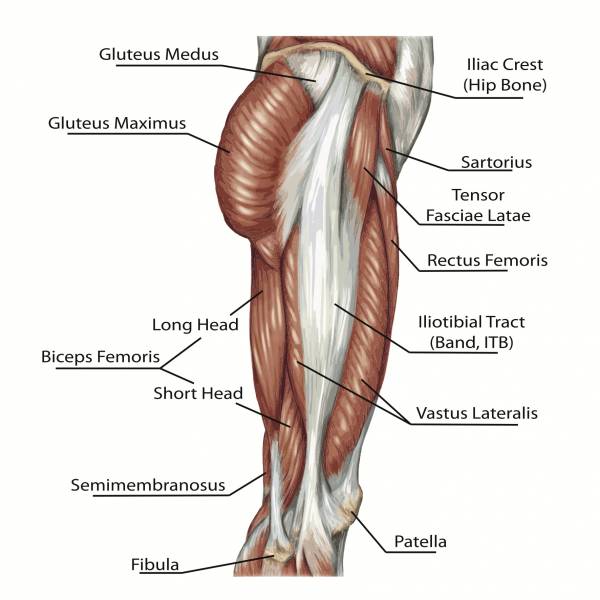

Almost all of the cases I treat stem from lack of core stability – specifically, from the lateral hip musculature (and yes, I group hip muscles into the core). Certainly you could see how this may be true if I were to only specialize in lower extremity treatment, but since I am telling you one of the secrets to my success, you should know that hip dysfunction also explains almost all of my waist-up cases (the technical term). As we go about our day-to-day lives moving from point A to point B, much of our activity requires us to move forward, or in the sagittal plane. Marathon runners, swimmers, point guards, and quarterbacks all have their eyes on the prize, in front of them. In order to produce any movement in this front-to-back plane, we must be able to use our lateral stabilizers, or anti-rotators, in the right amount, at the right time. Piece of cake, right? Now stabilize your core and control functional, diagonal, movements. Bob and weave, pivot and cut, juke your guy out of his cleats. Better have hips that would make Shakira drool.

The hip muscles – the glutes, the deep rotators, and yes those adductors that seem like they only exist to cause problems – are collectively charged with the daunting task of stabilizing everything above and below the hip. For example, as we walk, when we stride forward the standing hip must provide the force needed to prevent our torsos from dropping side to side and hold the hip and pelvis stationary (relatively speaking) to allow the knee to perform the simple hinge action for which it was designed. With such a large role, you can easily see how individuals of all abilities would have difficulty successfully controlling this multi-planar joint and the real trouble begins when compensations set in.

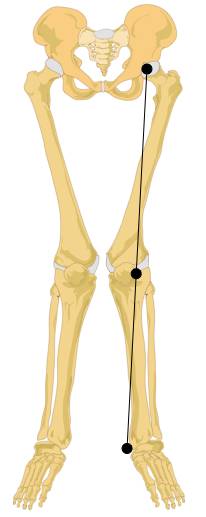

Let’s start with the Trendelenburg gait. This is a dysfunctional movement pattern we physical therapists are taught ad nauseam and love to point out during gait analysis. “Ooh, ooh! His pelvis dropped to the contralateral side, Trendelenburg!” This gait pattern occurs due to weakness of primarily the gluteus medius. We learn that this hallmark sign of lateral hip weakness can be spotted when the non-weight bearing hip drops lower than the level of the standing hip. Since we go to school for a really long time, we also learn that some individuals will compensate for this weakness by leaning their torso toward the side of weakness. You can assess this by watching someone walk, or stand on one leg. In our advanced classes, we learn that the glute med (we are older and cooler, so we abbreviate now) is also a rotator and when it is weak, the knee caves into an ugly valgus position (pictured right) because the hip dropped into internal rotation, straining the medial aspect of the knee.

Let’s start with the Trendelenburg gait. This is a dysfunctional movement pattern we physical therapists are taught ad nauseam and love to point out during gait analysis. “Ooh, ooh! His pelvis dropped to the contralateral side, Trendelenburg!” This gait pattern occurs due to weakness of primarily the gluteus medius. We learn that this hallmark sign of lateral hip weakness can be spotted when the non-weight bearing hip drops lower than the level of the standing hip. Since we go to school for a really long time, we also learn that some individuals will compensate for this weakness by leaning their torso toward the side of weakness. You can assess this by watching someone walk, or stand on one leg. In our advanced classes, we learn that the glute med (we are older and cooler, so we abbreviate now) is also a rotator and when it is weak, the knee caves into an ugly valgus position (pictured right) because the hip dropped into internal rotation, straining the medial aspect of the knee.

When you zoom the microscope out, you can see that hip weakness looks like a lot of things, not just the Trendelenburg sign. Often, there are no deviations in sight and more importantly, the negative effects have far greater reach than just pain at the hip or the knee. My athletes have shown me time and time again that when one movement strategy fails, they have an arsenal of second and third-string muscles ready to take over. Being able to substitute muscles in a time of need makes for a great short term strategy, however if such compensations are sustained over time, you will eventually see a plateau in performance and breakdown of muscles that are doing someone else’s job in addition to their own. Have you ever had to pitch in a little extra to make up for a colleague or teammate? Sooner or later being taken advantage of will get old.

Instead of demonstrating “down and in” collapse at the knee and ankle, the posterior tibialis at the inner shin can do a great job of lifting the arch and reducing the knee valgus. The posterior tib also excels in causing debilitating shin splints when used to do more work than it is supposed to.

Instead of demonstrating “down and in” collapse at the knee and ankle, the posterior tibialis at the inner shin can do a great job of lifting the arch and reducing the knee valgus. The posterior tib also excels in causing debilitating shin splints when used to do more work than it is supposed to. - The sartorius is an abductor and external rotator of the hip and with connections at the anterior hip and the medial knee, like the posterior tib, this long strappy muscle can pull the knee up and out when it contracts. Makes a good substitute for the glute med, right? Absolutely, with hip and knee pain to boot.

- If the glute max slacks off and lets your torso lean too far forward, the ankle plantarflexors are ready and willing and help hold you up. How much weight do you think your calf muscles can squat? You get the point.

The secret should be pretty clear by now – by mastering hip control in all planes, you can control whatever kind of movement you would like your body to create. You can be as static or dynamic as the hip allows. When the body works how it is designed, it is a powerful machine capable of both force and finesse. Big muscles do the heavy lifting while small muscles make minor adjustments. This results in efficient (read: strong and safe) movements. Control your hip, and you control your body.

Don’t miss part 2 in the series: It’s All in the Hip: 5 Steps to Fixing Movement Dysfunction.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.

Valgus knee graphic by LadyofHats, Jecowa, Stündle (File:Human skeleton front en.svg) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons.