In our modern society, we associate coddling ourselves with being healthy. We obsess over antibacterial rooms while sitting in our comfortable chairs. We shield our children from dirt and discomfort. But just as an overprotective parent can lead to fragile children, coddling your body can make you weak.

Exercise leads to adaptations that make you more resilient.

The Story of Mithridates

Mithridates VI was King of Greece from 120-63 BC. His father was king before him. If you think being born to royalty is easy, Mithridates is the exception. His father was poisoned by his mother. His mother also tried to poison Mithridates, as she wanted his brother to be king. Mithridates went into hiding to avoid being killed. During that time he took small doses of poisons with the hope that his body would become immune to their effects. His plan seemed to work, as he survived many attempts at poisoning during his rule. This is why the process of using small doses of a poison to build immunity is known as Mithridatism.

Mithridatism is still used today across multiple disciplines:

- It works to treat allergies. Small doses of an allergenic substance are given to the person to change their immune response.

- It is also used to treat anxiety. People with anxiety gradually face their fears until they become sensitized to their fear.

- This process also works with exercise. The stress from exercise improves your capacity to withstand greater stress. Hence, you get stronger by stressing yourself.

The Aging and Recovery Process Are the Same

Exercise exposes you to thermal, metabolic, hypoxic, oxidative, and mechanical stress. Each type of stressor stimulates a different recovery process.

One recovery trigger is known as mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS). When you exercise, your mitochondria provide your muscles with energy. In the process of producing energy, you release ROS, which promotes mitochondrial biogenesis (endurance) and hypertrophy (muscle growth). In this case, ROS acts as a ‘eustress,’ which is a positive stress that leads to adaptation.

You might have heard ROS referred to as “free radicals.” Free radicals are thought to lead to oxidative stress and aging. The same process that helps you recover from exercise also causes you to age. The amount of ROS released determines whether this process is adaptive or damaging. Exercise produces a small dose of ROS, leading to adaptations that make you more resilient. Just as Mithridates took small doses of poisons to lead to greater immunity, exercise leads to adaptations that protect you from aging.

Pampering is a Problem

Pampering yourself gets in the way of the ROS process. One such indulgence is the overuse of antioxidants. Recent research has indicated that antioxidants limit the benefits of exercise. For example, Gliemann and colleagues investigated the use of resveratrol after exercise.5 The participants taking resveratrol supplements did not improve cardiovascular indicators as much as participants who took the supplements.

“You don’t have to give up drinking wine or eating blueberries. Just avoid taking high-dose antioxidant supplements with amounts that are much higher than what we find in food.”

These conflicting results are difficult. On one hand, we have an argument in favor of antioxidants, due to their ability to reduce the effects of aging. On the other hand, we have an argument against antioxidants as not allowing for the benefits of post-exercise adaptation.

The correct answer is somewhere in between. You don’t have to give up drinking wine or eating blueberries. Just avoid taking high-dose antioxidant supplements with amounts that are much higher than what we find in food. We can also time our eating, and consume high-antioxidant foods on days of less exercise. So don’t eat three pounds of spinach following your workout. Save the spinach binge for your off day.

How We Spoil Our Bodies

Other examples of areas where we coddle ourselves include:

- Overuse of antibacterial products: A good amount of literature suggests antibiotics created drug-resistant bugs. Dirt microbes are also associated with lowered obesity rates and enhanced immune functioning. The take-home message is that playing in the dirt is good for you in limited doses. Throw out your antibacterial lotions.

- Comfortable office chairs: Breaking Muscle has an assortment of articles on the benefits of standing desks and how sitting is bad for you. By using standing desks, we build movement into our work day.

- Gloves and weight belts: If you are aiming for a powerlifting or weightlifting world record, by all means, use a belt. The rest of us can learn to brace ourselves and build stronger backs in the process. Pavel Tsatsouline once said that we can build our own belt by learning proper bracing. He has also commented about wearing “sissy” gloves to the gym. Build your callouses to protect your hands later.

Too Much of a Good Thing Can Be Bad

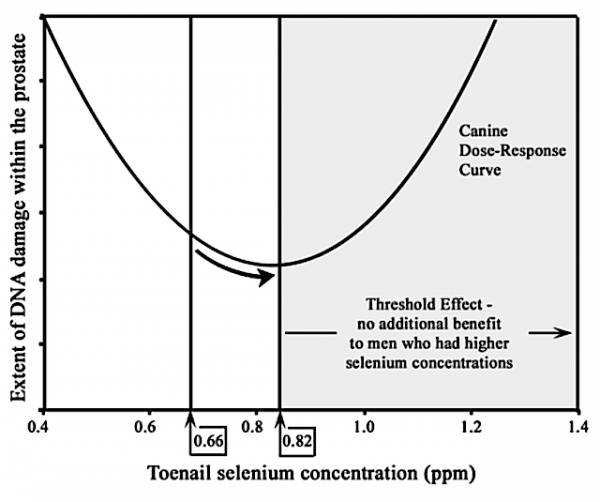

Toxicologists use a U-shaped curve to depict how toxins affect our bodies. In the curve below, we can see how selenium affects the risk of prostate cancer. If our selenium concentration is too low, we are at higher risk. But too high of a selenium concentration also puts us at risk. There is a point where increasing selenium reduces the risk for cancer, and also a tipping point where taking more increases the risk.11

We could model exercise with the same type of curve.

Following these U-shaped toxicology curves is good advice, but it is a bit more sophisticated than “everything in moderation.” The steepness of the curve changes for each substance and activity. You can eat more spinach before you reach the upside of the curve than you can eat a toxic substance.

We could model exercise with the same type of curve. We know the ROS process helps build mitochondrial functioning (our endurance system). Too much glycolytic training impairs mitochondrial growth and may cause mitochondrial damage. Too many workouts that leave you lying on the ground are not good for you, and might have the opposite training effect in the long term.

The body needs to learn to push through pain, but it also needs to be able to train again tomorrow. Figuring out that balance is important. I have been working with Pavel Tsatsouline on anti-glycolytic training protocols for CrossFit athletes. In a few weeks, we will present one of these protocols.

Make Use of the U-Shaped Curve

We can all follow the toxicologist’s U-shaped curve to determine what is good for us. Some things that are traditionally thought to harm us will actually make us stronger – up to a point. Exercise is a great example. The process set off by exercise is also thought to lead to aging. But with exercise, it leads to adaptations and makes us stronger.

Mithridates found the right amount of poison to make him immune to its effects. We can do the same by pushing into discomfort and then backing off.

Take Away Points

- Putting yourself through stressors can lead to adaptations that make you stronger. Look for situations that can stress you appropriately and make you more hardy.

- Pampering yourself with too much antioxidant supplementation might lead to reduced adaptation from exercise. Avoid high doses of antioxidants following exercise.

- Too much stress can lead to a breakdown of the body. Avoid too much glycolytic training to prevent mitochondrial breakdown.

Additional Reading:

- Do Antioxidants Impede the Benefits of Exercise?

- Antioxidants Have Mixed Effects on Performance

- Question Everything: Get Stronger With a Scientist’s Mind

- What’s New on Breaking Muscle Today

References:

1. Alleman, R. J., Stewart, L. M., Tsang, A. M., and Brown, D. A., “Why Does Exercise ‘Trigger’ Adaptive Protective Responses in the Heart?,” Dose-Response (2015): 13(1), doi:10.2203/dose-response.14-023.

2. Calabrese, Edward J., and Linda A. Baldwin, “The Frequency of U-Shaped Dose Responses in the Toxicological Literature,” Toxicological Sciences 62(2) (2001): 330–38, doi:10.1093/toxsci/62.2.330.

3. Davies, J., “Inactivation of antibiotics and the dissemination of resistance genes,” Science, 264(5157) (1994), 375–382, doi:10.1126/science.8153624.

4. Gao, Chao, Xiaoqian Chen, Juan Li, Yanyan Li, Yuhan Tang, Liang Liu, Shaodan Chen, Haiyan Yu, Liegang Liu, and Ping Yao, “Myocardial Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress and Dysfunction in Intense Exercise: Regulatory Effects of Quercetin,” European Journal of Applied Physiology 114(4) (2014): 695–705, doi:10.1007/s00421-013-2802-9.

5. Gliemann, L., et al., “Resveratrol Blunts the Positive Effects of Exercise Training on Cardiovascular Health in Aged Men,” The Journal of Physiology 591(Pt 20) (2013): 5047–59, doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2013.258061.

6. Muller FL, Lustgarten MS, Jang Y, et al., “Trends in oxidative aging theories,” Free Radic Biol Med Aug 10;43(4) (2007):477-503.

7. Paulsen, G., et al. 2014. “Vitamin C and E Supplementation Hampers Cellular Adaptation to Endurance Training in Humans: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial, “The Journal of Physiology, February (2014), doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2013.267419.

8. Peake, Jonathan M., James F. Markworth, Kazunori Nosaka, Truls Raastad, Glenn D. Wadley, and Vernon G. Coffey, “Modulating Exercise-Induced Hormesis: Does Less Equal More?” Journal of Applied Physiology (2015) jap – 01055.

9. Ristow, M., et al., “Antioxidants Prevent Health-Promoting Effects of Physical Exercise in Humans,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106(21) (2009): 8665–70, doi:10.1073/pnas.0903485106.

Schmaus, BJ., et al., “Gender and Stress: Differential Psychophysiological Reactivity to Stress Reexposure in the Laboratory,” International Journal of Psychophysiology 69(2) (2008): 101–6.

10. Scribbans, TD., et al., “Resveratrol Supplementation Does Not Augment Performance Adaptations or Fibre-Type–specific Responses to High-Intensity Interval Training in Humans,” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 39(11) (2014): 1305–13, doi:10.1139/apnm-2014-0070.

11. Waters, David J., Shuren Shen, Lawrence T. Glickman, Dawn M. Cooley, David G. Bostwick, Junqi Qian, Gerald F. Combs, and J. Steven Morris, “Prostate Cancer Risk and DNA Damage: Translational Significance of Selenium Supplementation in a Canine Model,” doi:carcin.oxfordjournals.org.

Photo courtesy of Recon Photography.

Chart courtesy of Oxford Journals.