One of the things I think CrossFit does well is encouraging people to work a broad range of physical skills. You know – broad time and modal domains. Because CrossFit’s goal is to increase GPP (general physical preparedness), it advocates using a variety of means to get there. After all, if you only use one tool or train in a single rep range, how “general” is it going to be?

One of the reasons I got into doing different events was solely as a way to test how my own training was going. If you ever want to see how useful your training plan is then sign up for an event, any event, and see what kind of result you get. If the result is favorable then you’ve done well, but if not then it’s time to go back to the drawing board and reconfigure your training.

For many testing the effectiveness of their workouts is an uncomfortable position to be in because they have a lot invested in a particular style of training or the use of a specific tool. I can’t even count how many conversations I have had with people along the lines of, “Well, I didn’t have the best race, but if I just go back and do exactly the same thing that led to my poor performance this time, then I’m sure I’ll have a better result next time.” Madness.

Using a Spartan Race (and myself) as an example, let’s look to see what can be changed from my last race to ensure better performance next time around:

Factor #1: Overall Run Fitness

When you reduce an obstacle course race to its core elements, they are still running races. That means you need to run. While I had a decent running base courtesy of Ironman in March, I hadn’t actually spent near enough time running as I would have liked. When you add in that instead of performing my normal weekend long run, I was spending time making sure my clients entering the race were doing theirs I had nowhere near enough running in my legs.

People make the mistake of looking at the distances and number of obstacles in these races and saying something like, “Oh, 14km and twenty obstacles. That’s only 700m of running at a time.” Well, maybe. But in the 14km race I did recently there were some long stretches of running unbroken by any obstacles, and many of these stretches were uphill. I know many of my clients were starting to go dead in the legs in the final third of the race.

The basic formula for an event like this, based on a formula I found works well for triathlon, is that you need the amount of running for the race times a factor of 2.8 in your training week. So a 14km race means we need roughly 40km of running in training. This then gets broken into sevenths. I’ll explain:

We are going to use four runs per week. Two of these runs account for a seventh each of the total distance for the week. We will have a medium run, which accounts for two sevenths. And a long run that accounts for three sevenths.

So in our 40km plan that means we’ll have:

- 2 x 5.5-6km runs

- 1 x 11-11.5km run

- 1 x 17-18km run

Our plan would go something like this:

- Monday – off running

- Tuesday – short run of 5.5-6km

- Wednesday – off running

- Thursday – 11km run

- Friday – off running

- Saturday – 6km run

- Sunday – 18km run

One of the things about Spartan is that they use the terrain as another obstacle. The only difference is you don’t deal with it once and then leave it behind – it’s with you all the way to the finish. With that in mind, I would add more hill running into the mix with the above run template. I know many would go nuts about speed work and track intervals, but my feeling on speed work is that it’s like the icing on the cake. The problem is most people don’t have any cake, which in this case is a big enough aerobic base, to make the icing (speed work) worthwhile. Always go for the cake in training, not the icing.

One of the things about Spartan is that they use the terrain as another obstacle. The only difference is you don’t deal with it once and then leave it behind – it’s with you all the way to the finish. With that in mind, I would add more hill running into the mix with the above run template. I know many would go nuts about speed work and track intervals, but my feeling on speed work is that it’s like the icing on the cake. The problem is most people don’t have any cake, which in this case is a big enough aerobic base, to make the icing (speed work) worthwhile. Always go for the cake in training, not the icing.

Factor #2: Tackling Obstacles

One of the drawbacks to obstacle course racing is that at times there can be a bit of a wait for obstacles. I have to say that I thought the Spartan organizers did a great job and I can’t actually remember a time when I wished people would just get out of the way and hurry up except for when crawling under barbed wire. Crawling low isn’t easy for many. The thing that slows them down is being really tight through the abductors, which means their butt sticks way up in the air and they get snagged. The solution is easy – spend time stretching doing frog stretches, can openers, and Cossacks. Then just spend time crawling.

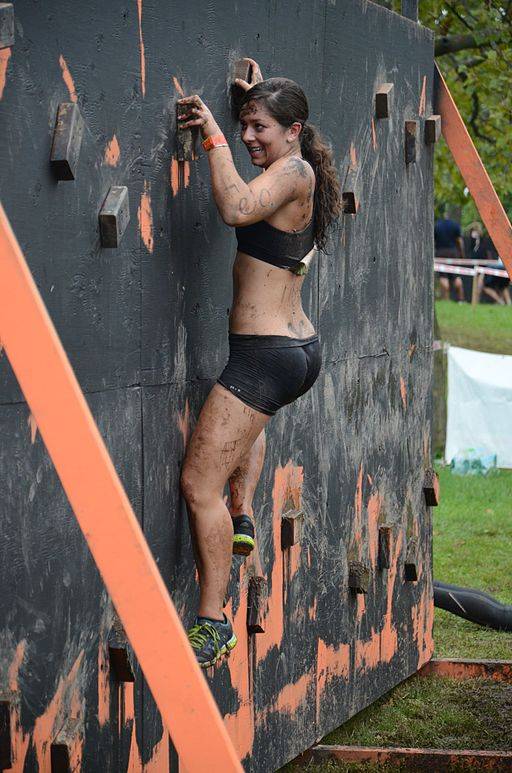

I know many people worry the most about the rope climb but the reality is rope climbing is easy and there are other obstacles that require more focus than that. The monkey bars seem to give a lot of women problems. The other main problem area was the higher walls that require a lot of upper body strength to get over. The solution to both of these is the same – more pull ups. Developing both pulling and grip strength will go a long way to helping people power over obstacles, as well as making other obstacles like carries, drags, and rope climbs easier.

Factor #3: Strength Training

One of the things about endurance racing is that any extra body weight quickly adds up. Even a couple of kilos of extra weight can mean having to deal with as much as 50,400kg extra on even a 7km course. (2kg x 3 as force per step x 1200 steps per km x 7km). So while you want to minimize body fat you also want to minimize body weight too. This means you need to be careful that your strength work doesn’t add too much muscle to your frame. Looking at the top obstacle course racers you’d be forgiven for thinking they are runners who got a bit big, but they are still far less bulky than your average CrossFitter.

The best way to accomplish as much strength as possible, while being as lean as possible is with a low frequency, low volume strength plan. Barry Ross has some great ideas on this and his plan for speedster Alyson Felix is KISS simple – 2 sets of deadlifts, followed by plyometrics, and a set of plyometric push ups.

The best way to accomplish as much strength as possible, while being as lean as possible is with a low frequency, low volume strength plan. Barry Ross has some great ideas on this and his plan for speedster Alyson Felix is KISS simple – 2 sets of deadlifts, followed by plyometrics, and a set of plyometric push ups.

I think for a pure runner that is a great start, however obstacle course racers will need a little more muscle than that, so we can add in a few sets of low rep pull ups too. At this point people will think they need to go all crazy and start busting out the WODs to get ready. But remember, it’s still a running race and if you have more energy, then add running to your schedule, not strength work. Given most obstacles are over in a short time frame – less than ten seconds for the vast majority – you don’t need much anaerobic WOD-type work, and given gains in that area come within four to six weeks I would wait until just prior to your race before instituting it.

Perform, Assess, Adapt

Performance, or improving it, is really simple. You make an educated guess as to what is needed for your event. You stick to that plan and see what happens. At the finish line you’ll know what worked and what didn’t. Insanity would be keeping the same training plan for the next event that led to a poor showing in the last event. My personal plan is to decrease some of my other points of focus, such as swimming and riding, and spend more time running before my next race. One of the good things about being in Australia versus the United States is that there is actually a decent gap between obstacle course events, so you have a long time to really get into the new plan. Having said that, it’s also a negative given that if the plan doesn’t work so well you’ll have dedicated considerable time to it before realizing it doesn’t deliver.

Don’t feel beholden to one plan, method, or system. Use what works and discard what doesn’t. Use the racing to assess your methodology. The final piece of advice is to not listen to what the couch dwellers tell you, either. The number one way to get messed up before an event is to listen to all the advice friends who don’t know anything about your endeavor will try to tell you. Trust yourself and what your race results tell you, and make a plan that fits.

Photos 1&2 by Senior Airman Jeremy Bowcock [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 3 by Edwin Martinez from The Bronx (Spartan 2 336) [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons.