For several years, at four different universities, I beat my brains out, attempting to find the ultimate training plan. Independent of any particular sport, I sought the most logical means of addressing all athletically desirable goals:

- Muscular strength and power

- Hypertrophy

- Fat loss

- Cardiorespiratory endurance

- Speed, quickness, and agility

- Joint flexibility and stability

- Injury prevention

How can all of those be addressed within limited training time, unmotivated athletes, and limited resources?

Programming Is More Than Sets and Reps

Let’s break these goals down into their fundamental requirements:

- There must be a well-planned program that addresses the desired qualities.

- There must be an overload effect from applied stress.

- Time must be allowed for proper nutritional intake and healing for adaptation to that overload stress.

- The plan must be progressive, increasing the overload over time as the body adapts to existing levels.

So far, so good. However, recovery can throw a wrench in the works. Without as much attention placed on it as the workouts themselves, overtraining can rear its ugly head, leaving you with athletes who have:

- Difficulty progressing in workouts

- Increased potential for injury

- Increased risk of illness

- Decreased performance in competition

- Apathy toward training

In short, lack of proper recovery or too much training volume destroys everything else you’re trying to do.

Recovery Factors to Consider

Let’s consider some other factors in programming to ensure adequate recovery:

- Training components are normally scheduled within the five-day workweek at the college level.

- The imposed overload must be strong enough to create a demand on the system(s).

- Energy is required to meet that overload, then to recover from it. Many coaches forget that second part.

- Athletes also have other daily commitments, and are usually on their own when it comes to proper nutrition and rest (sleep) habits.

Adequate recovery from stressful exercise sessions does not necessarily conform to a 24-hour day, or a five-day work week. The greater the volume of work, the greater the recovery time required. Dig a deep hole, and it will take more time to fill in. Energy stores are depleted that must be replenished; muscle tissue is damaged that must be repaired.

When multiple adaptive responses are desired from one body (i.e., strength, endurance, speed) even more logical planning of the training stresses is required. The athlete doesn’t go to a closet mid-day, pull out a new body, and toss the fatigued one in the laundry basket. It’s the same body that needs to deal with all imposed stresses that day, until there is time for recovery. There is some overlap there, as some training components address multiple qualities simultaneously. For example, increased muscle strength can lead to improved running speed, all other factors remaining equal.

Even the average Joe Sit-at-a-desk-all-day requires recovery from a less-than-demanding lifestyle to do it day after day. How much more so, your hard-charging athletes?

And recovery isn’t just day-to-day. How long do your athletes rest between sets? Between interval runs, agility drills, and speed work? What work to rest ratios are needed? Moreover, what about two-a-days? Do you program strength training and conditioning on the same day? Speed work on a leg strength day? Which one to address first?

Say that your athletes have total body fatigue from a Monday workout. What should you do on Tuesday? Complete rest? But wait, that leaves only three more days to squeeze in more strength training, endurance running, speed work, etc. Help!

Programming Tips to Ensure Recovery

Don’t panic. Remember, the strength and conditioning coach at rival State U is dealing with the same dilemma. We know that rest days are just as important as work days, and that all training components require energy and create a recovery demand.

Take advantage of that training component overlap. Performing speed and agility work creates fatigue (a conditioning effect). Leg strengthening exercises in the weight room indirectly help running speed, and contribute to injury prevention.

Don’t be afraid to take what the calendar gives you. It’s okay (and necessary) to plan occasional complete rest days during the training week. They’ll give your athletes a chance to look after their academic commitments, and a day off can create greater enthusiasm when returning to training. Take advantage of scheduled school breaks (i.e., spring and between-term breaks) to ramp things up. In the offseason, you can challenge your athletes with more volume, and the net positive effects will carry over into the competitive season, when volume must decrease for game-day preparedness.

Example Training Plans for Planned Recovery

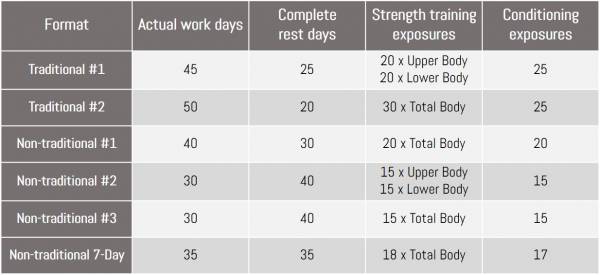

I recommend a maximum training segment duration of 8-10 weeks. Below are some example 10-week out-of-season training plans, broken down in terms of stress exposures and recovery time. I’ve laid out two traditional and three non-traditional plans for five days per week, and one non-traditional approach for seven days per week. Strength training (ST) is any weight room work. Conditioning (Cond.) would include any interval running, agility drills, or speed work.

Traditional Five-Day Plan #1

- Number of strength training sessions: 40 (20 each upper and lower body)

- Number of conditioning sessions: 25

- Total number of exercise sessions: 65

- Number of total rest days: 25

- Ratio of actual work days to total rest days: 45:25

Traditional Five-Day Plan #2

- Number of strength training sessions: 30

- Number of conditioning sessions: 25

- Total number of exercise sessions: 55

- Number of total rest days: 20

- Ratio of actual work days to total rest days: 50:20

Non-Traditional Five-Day Plan #1

- Number of strength training sessions: 20

- Number of conditioning sessions: 20

- Total number of exercise sessions: 40

- Number of total rest days: 30

- Ratio of actual work days to total rest days: 40:30

Non-Traditional Five-Day Plan #2

- Number of strength training sessions: 30 (15 each upper and lower body)

- Number of conditioning sessions: 15

- Total number of exercise sessions: 45

- Number of total rest days: 40

- Ratio of actual work days to total rest days: 30:40

Non-Traditional Five-Day Plan #3

- Number of strength training sessions: 15

- Number of conditioning sessions: 15

- Total number of exercise sessions: 30

- Number of total rest days: 40

- Ratio of actual work days to total rest days: 30:40

Non-Traditional Seven-Day Plan

- Number of strength training sessions: 18

- Number of conditioning sessions: 17

- Total number of exercise sessions: 35

- Number of total rest days: 35

- Ratio of actual work days to total rest days: 35:35

Training Plan Comparison and Discussion

If 10 sessions each of quality strength training and conditioning will result in good progress, imagine the results possible with the number of exposures offered in the non-traditional training formats above, especially coupled with a greater number of recovery days.

For example, the 15 upper body and 15 lower body strength sessions in the second non-traditional plan are plenty of opportunity to induce strength gains in a single out-of-season period. Also, 15 conditioning sessions are more than adequate to increase cardiorespiratory fitness. Note that 40 complete rest days are scheduled here to facilitate recovery from the 30 actual training days, making this a sound training plan.

The 7-day example uses 18 full-body strength training sessions and 17 conditioning sessions coupled with 35 complete rest days. Again, a more-than-adequate number of exercise exposures with plenty of built-in recovery time to allow for optimal adaptation.

Compare these to the traditional examples. In the first, 40 strength sessions and 25 conditioning exposures, but only 25 complete rest days in the 70-day plan. Overtraining may be more likely here. Similarly—and possibly quite worse than #1—example #2 is characterized by 30 full-body strength sessions, 25 conditioning workouts but only 20 complete rest days.

More is not always better when it comes to physical training. Properly planned overloads in the weight room and on the track must be logically placed over a training period, along with built-in recovery days. Train your athletes hard, but also train them intelligently.

Featured image: VK Studio/Shutterstock