A while back I stopped looking at what body parts were used during specific exercises. I got away from thinking that pressing was for shoulders and squats were for quads.

Instead, I started looking at what doing those exercises proved. A good squat shows me that you have the ability to flex and extend the hips bilaterally while maintaining a braced spine under load.

A while back I stopped looking at what body parts were used during specific exercises. I got away from thinking that pressing was for shoulders and squats were for quads.

Instead, I started looking at what doing those exercises proved. A good squat shows me that you have the ability to flex and extend the hips bilaterally while maintaining a braced spine under load.

While bigger quads might be on your wish list, the end goal of athletically good flexion and extension of the hips might be far more important. That’s running, jumping, kicking, and all manner of lifts like the clean and snatch. So squatting is important because if you do it well I know you’ve got the basic wiring in place to do all those other things well, too.

Squatting involves much more than stimulating quad growth.

Assessing New Clients

New clients at my gym are usually surprised at how technique driven the training staff is.

That’s not because I enjoy saying the same thing over and over just to hear the sound of my voice, believe me. Twenty years of repeating the same few sentences wears on you eventually.

We are technique driven because I want to help people develop the qualities necessary for their body to perform tasks outside the gym – you know, in a real-life situation where they are forced to use their “functional fitness.”

If you can’t display these qualities well in isolation inside the gym, then you have little chance to do so outside in the big, wide, chaotic world.

Everything Is a Plank

When I boil down what is needed for most lifts I get to a single core principle – the spine needs to remain stable.

I’m going to refrain from saying that the spine needs to be neutral, because many great lifters perform with bent spines. However, those bent spines are still braced and locked in position. Once the lift has begun, there is no movement of the spine. But semantics aside, let’s just start with a neural braced spine position for most.

The best way to figure out if someone can hold this is with the simple plank.

The plank is an important test for a variety of reasons. The most important of which is that because there is no movement involved, the trainee is able to feel exactly what it is you are trying to get him or her to understand. In my experience, the more moving parts there are, the more likely someone is to misunderstand what you’re trying to get across.

The plank is one of the most basic exercises you can perform, but also one of the most important.

Here’s how to plank, from my article Everything Is a Plank:

- Find where a neutral pelvis position is. I find the simplest way to do this is rock your pelvis back and forth until you find the spot where you can tense your glutes the hardest. When you find that spot where you can create maximal tension you’ll have found the spot where you are most likely neutral.

- Lock the ribs and pelvis together. Remember that the purpose of this exercise is to teach us to create a stiff link between upper and lower body. Letting your ribs and pelvis disassociate is a few steps away for us right now.

- Tighten the abs and breathe out. You’ll find that as you breathe out you can shrink-wrap your abs to create an even tighter brace. Don’t let it all go when you breathe in, only take short little sips of air, just enough to replenish what you breathe out. We call this breathing behind the shield – stay tight and protected. The main mechanism of spine injury is running out of work capacity or strength endurance, not of having not enough maximal strength to withstand a flexion incident.

But let’s not stop there. I want you to see just how important the plank is as a movement diagnosis. Literally everything you do athletically stems from this one position.

How to Assess Yourself

I want you to stand up and jump up and down lightly five or six times. Take note of how your feet land and whether or not they’re turned out at all. If you’re like most people, your feet will now be slightly pointed out.

You may even walk like that. And if you walk like that, there is a large chance you run like that. This turned-out position is a disaster from a core stability point of view, as you’re about to see.

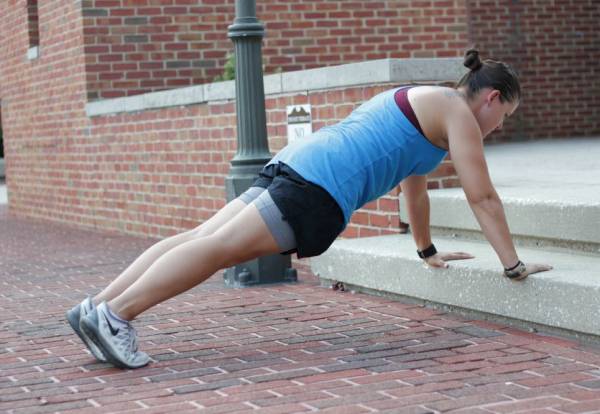

Go back to your plank position, using a push up plank (on your hands, not your elbows).

Instead of just assuming the position, try to make yourself as stiff as you can. Screw your hands into the ground. Tense the glutes. Wedge yourself between your hands and feet. Get a feeling for how tight you can make yourself. You won’t last long in this position – twenty seconds will feel like an eternity.

“Go back to absolute basics and see if you can actually hold it all together in the plank properly. Then slowly add movement back in once alignment and stiffness are properly learned.”

Now that you have a feeling for how stiff and braced you can be, we’re going to demonstrate how bad having your feet externally rotated is from a stability perspective:

- Return to your plank.

- Turn your feet out ninety degrees so they are pointing directly out to the sides and you are resting on the inside edge of your feet.

- From this position try to brace yourself as much as you did before. See if you can make yourself as stiff as you did the last time.

- If you really want to see how bad this can get, try pointing your fingers back toward your feet at the same time.

If the plank is our basic building block for core stability – a skill we need when doing all other athletic activities – how important is alignment?

In the plank, our feet are straight and we can achieve maximal stiffness. Once you start changing the alignment of the limbs, then you start to lose stiffness and open yourself up to injuries.

Running and Core Stability

Running is a particularly vivid example of this. Have you ever watched someone run duck footed?

The only way this can be accomplished is by dumping the pelvis, losing all core stability, and relying on the spine itself to hold the body together. Is it any wonder why these people complain about running hurting their backs?

Proper running involves having good core stability.

You’ll see this as you go up the chain of exercises, too. The client who has the turned-out feet will struggle with push ups (an example of a core-stability exercise with one set of limbs moving – the equivalent of half of running).

You’ll see it in crawling (midline stability while both sets of limbs move contralaterally – running, but more gentle). As you go from the ground to standing, you’ll see this same compensation over and over again.

The fix isn’t anywhere near as complicated as most running coaches would have you believe. Fix the core stability element at its simplest point – the plank – and you’ll fix it higher up the chain, too, once some relearning has taken place.

If you’re not getting the performance result you want, don’t try to attack the aspect with many moving parts first.

Go back to absolute basics and see if you can actually hold it all together in the plank properly. Then slowly add movement back in once alignment and stiffness are properly learned.

Check out these related articles:

- Everything Is a Plank

- A Simple Plan for Stronger Running

- Forget Crunches – How to Actually Strengthen Your Core

Photos courtesy of Breaking Muscle.