You often hear the term resilient in reference to sports, but first, let’s define resiliency in general terms. The American Psychological Association defines resilience as:

…the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or even significant sources of stress – such as family and relationship problems, serious health problems, or workplace and financial stressors. It means ‘bouncing back’ from difficult experiences.

By virtue of this definition alone, an athlete easily fits within the parameters of this description. Now, couple this psychology definition with the factors of opponents, fans, training, competitions, teammates, coaches and trainers, controllable and uncontrollable variables, and injuries. Who better to bounce back from the face of adversity or to bounce back from difficult experiences than an athlete?

Can Resilience Be Taught?

Athletes of all abilities, but especially high-performance athletes, must have resiliency in abundance in order to war with the dynamics of internal and external conflict. As Dr. Robert Heller, a psychologist and sports psychology consultant, attests, resiliency in sports is:

…one of the key mental attributes an individual or team player must have. The ability to come back from behind, to fight fiercely until the last second…

As psychologists, coaches, and trainers seek to understand and to train their athletes in the art of resiliency, the question arises – is resilience an innate trait or a trait that can be taught? All answers to this question seem to stem from the resiliency theory, which is broad based and may be applied across a variety of spectrums.

In essence, the resiliency theory is based on the principle that all people have the ability to overcome adversity and to succeed despite their life circumstances. The resiliency theory focuses on providing developmental support and opportunities to promote success, despite the mistakes or errors an individual makes.

The Resiliency Theory in Action

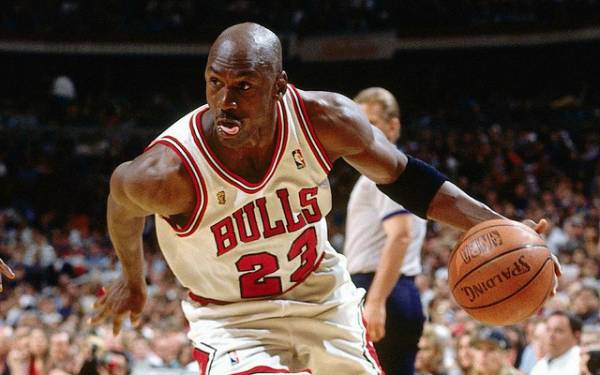

NBA star Michael Jordan (pictured below) is the epitome of resiliency in sports. Cut from his high school basketball team, he did not let this stop him from playing the game. In Bud Bilanich’s article, 50 Famous People Who Failed at Their First Attempt at Career Success, Michael Jordan states:

I have missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I have lost almost 300 games. On 26 occasions I have been entrusted to take the game winning shot, and I missed. I have failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.

This is the quintessential example of the value of resiliency in athleticism. Bo Hanson, a four-time rowing Olympian and now a coaching consultant and director of athlete assessments, also attests to the importance of resiliency in an athlete. Mr. Hanson acknowledges that while all athletes make mistakes, what sets an elite athlete apart from the norm is his or her ability to quickly recover from a mistake.

A 4 Step Process to Increase Resiliency

In researching the different ways to instruct and implement resilience in sports programs, I was struck by the lack of consistency and agreement in how to teach it. As stated above, we know that athletic resilience can be learned, but how can athletic resilience be taught?

In her article Overcoming Performance Errors with Resilience, Dr. Gloria B. Solomon, a specialist in sport psychology and a renowned sport sociologist, explores the subject. In collaboration with her colleague, A. Becker, Dr. Solomon developed a four-step process to help athletes deal with and learn from performance errors and to increase individual athletic resiliency. The simple mnemonic device, ARSE, (yes, really) follows:

- A = Acknowledge. The athlete acknowledges and accepts responsibility for his or her error and the frustration it has caused. Ownership of the error is essential in this phase of resiliency, as is acknowledging the frustration for the individual athlete, as well as for the team. ?

- R = Review. The athlete reviews the play and determines how and why the performance error occurred.

- S = Strategize. The athlete makes a plan to take corrective action for future plays. At this point, team members or coaches may also assist in corrective action, but again, the ownership for the performance error, as well as for the future strategy, belongs to the individual athlete.

- E = Execute. The athlete continues to perform in the event and prepares for the next play.

At first glance, it appears that this list will take time to enact, but in reality, as the athlete continually practices and implements this process, feedback will take seconds to accomplish. The faster the athlete realizes and actualizes this process, the more resilient the athlete becomes.

Practice Makes Resilient

Resiliency has become a popular buzzword in athletics and can encompass a wide range of situations. Despite myriad definitions and theories regarding resilience in athletics, one thing is certain – it is a highly desired and sought after athletic trait.

Through practice and repetition, feedback comes quickly, harkening back to Bo Hanson’s suggestion that elite athletes have an incredible recovery time from mistakes and errors. Drawing upon the necessity for trainers and coaches to adopt a resiliency plan and to teach athletes the ARSE method, we know that the art of resiliency can be a learned athletic trait.

References:

1. WestEd. “Resilience & Youth Development”. California Healthy Kids Survey. Accessed 10/6/14.

2. PsychCentral. “What is resilience?”. American Psychological Association. Accessed 10/6/14.

3. Solomon, G., “Overcoming Performance Errors with Resilience”. Association for Applied Sports Psychology. Accessed 10/06/14.

4. Hanson, B. “6 Ways to Improve an Athlete’s Resiliency.” Athlete Assessments. Accessed 10/06/14.

5. Bilanich, B.. “50 Famous People who Failed at their First Attempt at Career Success.” Bud Bilanich. Accessed 10/06/14.

6. Resilience Training Institute. Resilience Training Courses. Accessed 10/5/14.

Photos 1 & 3 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 “michaeljordan” by Jason H.Smith Attribution-NonCommercial License.