One of the more common complaints you hear from female athletes revolves around having a bit of difficulty holding their “water” during exercise (especially during impact activities like double unders). You may also see other athletes struggle to keep neutral posture during a movement such as the deadlift, snatch, or clean. Both of these problems have the same root source.

Lack of strength in some of the deeper core musculature means a loss of power, a loss of technique, and the possibility of injury – not to mention the occasional wet spot on the floor that has nothing to do with a “sweat angel.” Our core is the base we work from, with the intent of creating movement and power around a stable object. The problem is that the object (your spine) doesn’t stabilize itself – it takes effort.

Having good spinal stability is important to movement, injury prevention, and recovery from injury. Have a shoulder problem? Fix your posture. Does your knee hurt? Fix your posture. Headache? Fix your posture. It’s not the only answer to what’s ailing you, but it’s rarely not part of the answer. It’s just too important to miss, but people do anyway.

Ask yourself: When you “tighten your core,” what muscles are you using? Does your posture change? Does your pelvis tilt forward or backward? (Hint: if the answer to either of these last two questions is “yes,” then you’re doing it wrong.) So let’s take a look at what’s going on in your core, and how it should be working.

The Anatomy Behind a Stable Spine

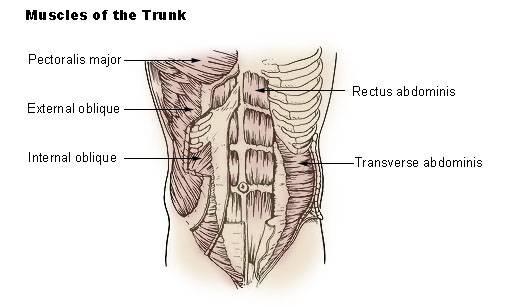

The transverse abdominal (TA) is located underneath all of your other abdominal musculature. It wraps around the sides and front of your abdomen, attaching to your lower ribs and pelvis. In the front, it forms a thick tendon sheet (aponeurosis). Its fibers are oriented horizontally (unlike rectus abdominals, which are vertical, or your obliques, which are, well, oblique). A proper TA contraction will act as a vacuum, pulling your abdomen in and creating intra-abdominal pressure and stability – but it doesn’t work alone. The action of the TA also incorporates your diaphragm, and has a partnership with your pelvic floor muscles and some small muscles in your back called your multifidi.

The Diaphragm

Your diaphragm is a bell-shaped muscle that helps you breathe. When you inhale properly, your diaphragm will flatten out and allow air to flow into the biggest part of your lungs (which are sort of shaped like a triangle). When your diaphragm contracts, it literally pushes your guts out (they’ve got to go somewhere after all). If you’re not sure what this looks like, go watch an infant breathe. We all start breathing this way, but then we often forget how to do it well as we get older. And guess what? Breathing properly creates intra-abdominal pressure too.

The Pelvic Floor

The muscles of your pelvic floor also work with the lower fibers of the TA muscle. For you women who pee when you exercise, this relationship cannot be ignored (and just because it’s common to pee when you exercise at high intensity doesn’t mean it’s normal). Not sure how to contract the pelvic floor muscles? Think about what you do every time you have to pee but aren’t near a toilet. In addition, there is some evidence that co-contracting your TA and pelvic floor muscles together will actually help you get a better contraction for both.

The muscles of your pelvic floor also work with the lower fibers of the TA muscle. For you women who pee when you exercise, this relationship cannot be ignored (and just because it’s common to pee when you exercise at high intensity doesn’t mean it’s normal). Not sure how to contract the pelvic floor muscles? Think about what you do every time you have to pee but aren’t near a toilet. In addition, there is some evidence that co-contracting your TA and pelvic floor muscles together will actually help you get a better contraction for both.

Multifidi

Your multifidi are small muscles that connect between two or three vertebrae in your spine. This is important because when they contract they help provide segmental stability to that region. They co-contract with your transverse abdominal muscle.

So, before you even begin a lift or movement, you’ve got a lot to think about. First you’re finding your neutral spine. Then, it’s time to put the aforementioned muscle complex into action to help stabilize the spine. For some this is easy, but for a lot of people this is quite difficult. In my clinic I find that a lot of my athletes struggle with this, as they tend to compensate with other abdominal musculature (usually obliques or rectus). It’s actually fairly common to have fitness instructors struggle with this for the same reason.

Do a Self-Test on Your Spinal Stabilization

Here’s how you can check to see if you are doing it right (and if you aren’t, this can also be used as a starting tool to work at getting it right):

- Lie on your back. Knees can be bent up our out straight, whatever’s comfortable

- Start by “belly breathing.” Take a deep breath in – your belly should rise. Exhale -your belly should fall. Take some nice deep breaths.

- Find the pointy parts of your pelvis in the front. You can start from just below your belly button and work out toward the bony prominence on either side. Now take two fingers and move about one third of the way between that part of your pelvis (it’s your anterior superior iliac spine, in case you want to Wikipedia it) and your belly button, and press in so you can feel the layer of muscle.

- Do a few more belly breaths and feel the rise and fall.

- As you exhale, try to draw your belly button toward the floor and your spine (this is shooting for your TA). If you can, at the same time contract the muscle you would use to stop yourself from peeing midstream (do this with an empty bladder).

If you get it right, you will feel your fingers dip down toward the ground. If you missed it, you will generally feel the abdominal wall push up into your fingers. You’re using rectus abdominal or obliques when the latter happens. In order to fix things, remember that less is more. Generally the more maximal the effort, the more likely you will compensate with other musculature. Once you get this exercise, then sustain the contraction for a ten count, but continue to belly breathe. This will feel slightly restricted, as you have literally given the diaphragm less room to move by not allowing it to shove your guts out.

If you get it right, you will feel your fingers dip down toward the ground. If you missed it, you will generally feel the abdominal wall push up into your fingers. You’re using rectus abdominal or obliques when the latter happens. In order to fix things, remember that less is more. Generally the more maximal the effort, the more likely you will compensate with other musculature. Once you get this exercise, then sustain the contraction for a ten count, but continue to belly breathe. This will feel slightly restricted, as you have literally given the diaphragm less room to move by not allowing it to shove your guts out.

Got it? Great! Now to be sure you can do this from any and every position you will possibly find yourself in. Practice doing the sequence above in the following positions: sitting, standing, moving from sitting to standing, squatting, during push ups, pull ups, wherever you are.

TA Complex Homework for Athletes

A couple of other things to bear in mind for when you use the TA-pelvic floor-diaphragm-multifidi complex correctly:

- Your posture won’t change. If you are changing your posture (pelvic tilt, increasing or decreasing the curve in your low back from neutral), then you are using the wrong musculature.

- It’s harder to sustain this contraction than you think. Try doing it in standing. Got it? Now keep it while you count backwards from a hundred by seven. Sustain it while trying to throw or catch a ball.

The TA complex’s purpose in life is spinal stability. Since you both have a common goal, why not work together a bit more?

Photo 1 courtesy of CrossFit LA.

Photo 2 by [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Photos 3 & 4 courtesy of Shutterstock.