How many times have you or someone you know, when discussing diet, weight loss, and exercise, groaned and complained about a slow metabolism? The phrase “I can just look at food and gain weight!” is something I’ve heard many times. I think I’ve said this a few times, too. Yes, many people do have endocrine problems that make weight loss harder. But, the vast majority of people who complain about their slow metabolisms don’t have a metabolism problem at all. They have a movement problem. A lack of movement, that is.

“But wait, I work out everyday. I’m super active! I definitely have a slow metabolism,” you might be saying. And maybe you do. But, let’s think about this for a minute or two. When it comes to weight loss or gain, we are playing a game of numbers for the most part. Too much food and not enough energy expenditure causes you to gain weight (be it fat or muscle or both, depending on the circumstances). The opposite is also true. Eat less and move more and you lose weight. Yes, folks, I’m simplifying things quite a bit here, but for the most part this is how it works. So, if we are having difficulty losing weight and blaming it on our metabolism but our blood work and hormones are actually in line, then we have to start thinking about where the problem really lies.

The Importance of NEAT

Your basal metabolic rate (BMR), plus the thermic effect of the foods you eat, added to something often referred to as Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) or Non-Exercise Physical Activity (NEPA) makes up your energy requirements for each day. NEAT or NEPA is a huge part of that equation and I’ll explain how.

BMR + thermic effect of food + NEAT/NEPA = daily energy requirement

BMR, or Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR), is the energy requirement of your body either without any activity or while lying motionless. BMR/RMR accounts for about 60% of your total daily energy requirements. The thermic effect of food (the amount of calories needed to digest food) accounts for about 10-15% of your energy requirements. The rest of your energy requirements are dependent on how active you are in both intentional exercise and NEAT/NEPA activities (normal life activities like cleaning, shopping, walking, etc.).

NEAT/NEPA can account for as little as 15% of energy expenditure in the very sedentary and up to 50% in very active individuals. If a woman has a BMR of around 1,000 calories (we’ll use that nice even number for simplicity’s sake), she’ll burn about 150 calories digesting the food she eats each day. She may also burn anywhere from 150 to 500 calories more per day depending on whether she has a day full of walking around, shopping, and cleaning or if she spends the day sitting and working on the computer.

We’re also going to say our person didn’t engage in any intentional exercise on this particular day. So, on the low end of things, she is going to burn 1,300 calories. If her NEAT activities are on the higher end, she’s going to burn 1,650. That’s a 350-calorie per day difference between those activity levels. Now, I don’t know many people who eat only 1,300 calories per day, but I know plenty of people who have office jobs and don’t workout. Couple a sedentary lifestyle with a daily surplus of calories beyond your basic energy requirements and over time you have weight gain.

The Truth About Your Activities

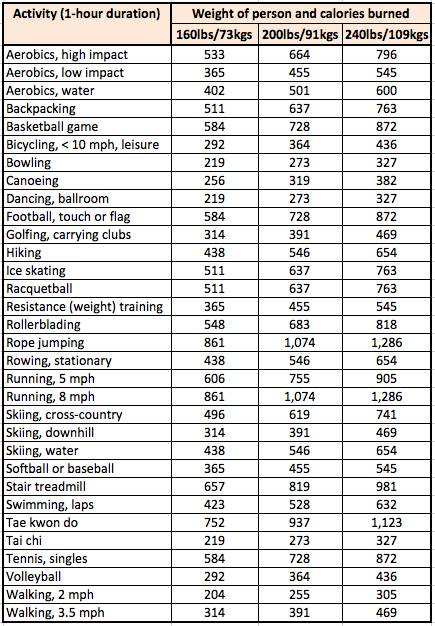

“But I workout! I’m super active,” you’re saying. Okay, I hear you. But, consider this: the average calories burned during an hour of intentional exercise is about 328 calories for every 100lbs of body weight. (This is an average and not extremely accurate, as everyone will differ based on unique factors such as lean body mass, BMR, etc.) Then consider that most of us aren’t engaging in a solid hour of nonstop exercise for an hour a day. I usually workout for over an hour daily (not nonstop, however), so it does happen, but it’s not typical.

“But I workout! I’m super active,” you’re saying. Okay, I hear you. But, consider this: the average calories burned during an hour of intentional exercise is about 328 calories for every 100lbs of body weight. (This is an average and not extremely accurate, as everyone will differ based on unique factors such as lean body mass, BMR, etc.) Then consider that most of us aren’t engaging in a solid hour of nonstop exercise for an hour a day. I usually workout for over an hour daily (not nonstop, however), so it does happen, but it’s not typical.

But get this – if you’re a 150lb women and you’re doing thirty minutes on the elliptical then you might only be burning 246 calories. That’s about the amount in two-tablespoons-plus-a-smidge of almond butter (which isn’t that much!).

And if you’re working out like a fiend and are still not where you want to be physically or in terms of body fat percentage, then consider the following. Multiple studies have shown that people who engage in intentional exercise either unconsciously either ate more to compensate or overcompensated for the calories burned by moving less after the exercise and thus negating their efforts to a degree. Translation: you can’t workout and then sit on your bootie all day, and you also can’t not account for that post-workout shake (or donut). It still counts, and you might even be negating your whole workout!

What “Naturally” Lean People Do

It’s easy to lose site of all this information when we compare ourselves to others who seem to effortlessly lose weight or stay lean. We often compare how much we are working out and how much we are eating, and then we blame our genetics for giving us this tortoise-like ability to lose fat. But, we don’t see what these “naturally skinny” people are doing on a regular basis.

My guess would be that your naturally-thin friend quite possibly has a very active job, as opposed to sitting at the computer or in meetings or answering the phone all day. “Naturally” thin people may also workout on top of their active jobs, adding to their daily calorie burn. Their metabolisms aren’t any better, they just move more. This daily surplus of movement and expended calories adds up over time, just as non-movement and surplus calories can.

My guess would be that your naturally-thin friend quite possibly has a very active job, as opposed to sitting at the computer or in meetings or answering the phone all day. “Naturally” thin people may also workout on top of their active jobs, adding to their daily calorie burn. Their metabolisms aren’t any better, they just move more. This daily surplus of movement and expended calories adds up over time, just as non-movement and surplus calories can.

The subtle but consistent differences in activity and lifestyle make it appear that we have two camps: those who stay thin effortlessly and those who do not. But really it’s a case of those who are active in an effortless or routine way and those who are not active. So, maybe you don’t have a slow metabolism at all. Maybe you just need to get out of your desk chair?

References:

1. Levine, James. “Nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): environment and biology.” American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology and Metabolism. no. E675-E685 (2004). 10.1152/ajpendo.00562.2003 (accessed December 15, 2013).

Images 1&3 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Chart adapted from Ainsworth BE, et al, “Compendium of physical activities: A second update of codes and MET values.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2011;43:1575.