With such a provocative title, this article is not going to be preaching the virtues of drug-free sport. Rather, it will be discussing the long-term advantageous effects (potentially lifelong effects) that anabolic steroids confer on the muscles of former users. Therefore the question, is it ever possible to complete “clean” again?

With such a provocative title, this article is not going to be preaching the virtues of drug-free sport. Rather, it will be discussing the long-term advantageous effects (potentially lifelong effects) that anabolic steroids confer on the muscles of former users. Therefore the question, is it ever possible to complete “clean” again?

How fast or strong an athlete can get in any sport is limited by their genetic potential. What I mean by this is the maximum level of performance that can be achieved by optimum training, recovery, nutrition, skill development, and all other factors that contribute to performance, without performance enhancing substances like steroids. Now at the risk of stating the bleeding obvious, not everyone’s natural sporting potential is the same. If you’re an Average Joe, it won’t matter how much training and performance enhancing substances you take, thousands of adolescents around the world will still crush you (no matter what your sport), simply because your genetics are not good enough.

But this isn’t the argument I’m making here. The point of this article is to examine and explain the evidence indicating that anabolic steroids permanently increase a user’s sporting potential such that they can never compete evenly against drug-free athletes again.

The usual reasoning for the beneficial effects of anabolic steroids on athletic performance goes something like this:

- Your natural hormone production is able to support a given muscle mass and speed of recovery from training.

- Injecting synthetic hormones (i.e. steroids, testosterone, etc.) will let you support more mass and recover faster.

- Ceasing steroid use means you go back to your natural hormone levels and therefore your natural muscle mass.

Based on this reasoning, the standard bans from governing bodies of six to 24 months from competitive sport seem reasonable. And it is assumed that after being drug-free for several months to years, any hormonal advantages would be washed out, and the playing field would once again be “even.” These athletes would now be considered to be clean again.

Why Is This Wrong?

Evidence is now showing that in addition to increasing the anabolic (pro-growth) hormone levels in the body, anabolic steroids fundamentally change muscle fibers such that their potential for size and strength is permanently increased.

A study from Sweden has examined the muscles of three groups of powerlifters:

- Powerlifters who are currently using steroids and training.

- Powerlifters who have a history steroid use, but have not used steroids in several years and no longer performed strength training (i.e. are sedentary, de-trained).

- Powerlifters who have never used steroids and are currently training.

The former steroid users had used testosterone in combination with various anabolic steroids (nandrolone, stanozolol, Primobolan, oxymetholone, Masteron, Proviron, and durobolan). The researchers looked at two muscles: the vastus lateralis, (in the quadriceps), and the trapezius (in the shoulder-neck). Both muscles critical to the sport of powerlifting.

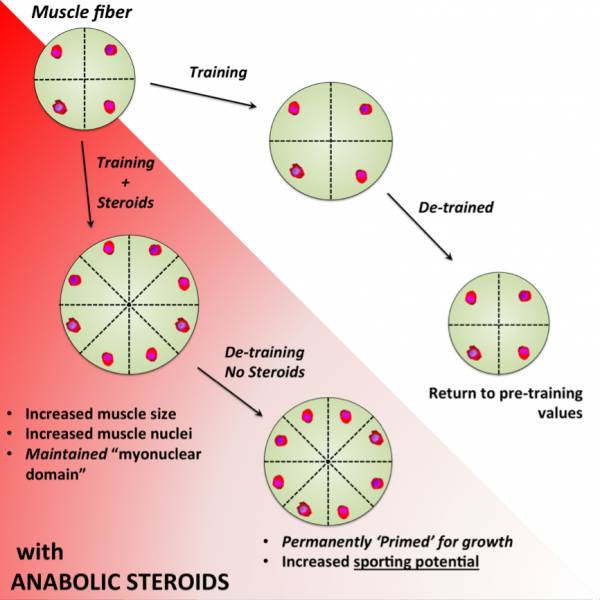

The findings have been summarized in the figure, outlining what seems to be happening within muscle fibers of steroid users during and after ceasing steroid use. In short, the researchers found that even with several years of anabolic steroid withdrawal and a lack of strength training, important characteristics of muscle were permanently altered. These changes provide an advantage for strength performance and muscle growth many years after drug use has stopped.

Now let’s get down to the nitty-gritty of what is going on within the muscle fibers using the concept of the myonuclear domain. In each muscle fiber, there are multiple nuclei (shown as pink dots in the figure), which are required to send out messages for muscle fiber repair and growth in response to training and overload. This results in the deposition of new muscle tissue, causing growth known as hypertrophy. The resulting muscle is now bigger and stronger. Evidence shows that the number of nuclei generally remains proportional to the size of the muscle fiber, meaning that when a muscle fiber grows, the number of nuclei also increases. Each muscle (myo) nuclei is thought to control a domain within a muscle fiber (myonuclear domain). These are represented by the dotted sections in the Figure.

Examining the muscles of former powerlifters who have used steroids in the past, but not for several years, their muscle fiber size remains elevated. And importantly the number of nuclei per muscle fiber remains comparable to the lifters currently training and using steroids, and significantly higher than lifters who are currently training and had never used steroids.

While this higher number of nuclei per fiber is only one aspect controlling muscle adaptability to training, it is likely to be highly beneficial to an athlete who resumes training. Previous steroid use, even years earlier, will allow for more protein synthesis, faster protein deposition, and more rapid increases in muscle mass and strength.

While it is unknown exactly how long these beneficial changes remain, it is likely that this increase in sporting potential means that the playing field is not even for many years after banned athletes are back competing and considered to be “clean.”

References:

1. Eriksson A, Kadi F, Malm C, Thornell LE. Skeletal muscle morphology in power-lifters with and without anabolic steroids. Histochem Cell Biol, 124 (2005): 167-75.

2. Kadi F, Schjerling P, Andersen LL, Charifi N, Madsen JL, Christensen LR, Andersen JL. The effects of heavy resistance training and detraining on satellite cells in human skeletal muscles. J Physiol, 558 (2004): 1005-12.

3. Kadi F, Eriksson A, Holmner S, Thornell LE. Effects of anabolic steroids on the muscle cells of strength-trained athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 31 (1999): 1528-34.

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.