Before embarking on any form of training whether it be as a tactical athlete or complete beginner to exercise, it is important for us to have our mind in the right place. Getting up at 0500 in the snow to run a thirty-miler across Dartmoor takes a certain amount of mental toughness (or stupidity).

As the television ads suggest, earning a green beret is a state of mind, but what implication does our state of mind have on our physical performance?

Getting in the zone allows the athlete to elicit the best possible results from their training.

The Tactical Athlete’s Perspective

During my time as a tactical athlete, the vast majority being spent with Commando forces, I quickly discovered I needed to become happy with being uncomfortable. The feeling of your stomach churning with the eyes of the Commando training center looking down on you while you stand at the bottom of a thirty-foot rope, soaked to the bone on a cold winter’s morning, is something I could never replicate in the gym.

“Test day came with the added pressure of having to perform and brought a heightened psychological state that manifested itself physically.”

I struggled with the thirty-foot rope climb, especially when loaded with fifteen pounds of gear and a weapon. And on test day, we weighed a hell of a lot more due to all our gear being soaked through. I’ve always been physically strong, but I lacked the technique to climb a rope. It was hit and miss with me all the way up to test day.

But test day felt different. I felt psyched up. Test day came with the added pressure of having to perform and brought a heightened psychological state that manifested itself physically. While standing there shaking and sweating, I couldn’t help but wonder what effect this was going to have on my performance.

Anxiety Versus Arousal

Although I do kind of enjoy being put through physical hell, I don’t think it arouses me in the typical sense. Within sports science, arousal is a feeling of positive energy.1 When it comes to game day, these feelings may be perceived as being anxious. There’s a fine line between anxiety, which can have a negative effect on performance, and arousal, which can have positive influences on our physical prowess.

“We must learn to accept and appreciate what impact arousal has on performance. The physical manifestation of arousal displayed through butterflies, shakiness, and increased heart rate is not something to be afraid of.”

Turning these feelings into a display of physical dominance in one of the most physically and psychologically draining environments in the world is all about getting your mind state in check. You can, must, and will complete the task at hand.

Putting this positive state of mind in place allows for extraordinary feats of strength. Arousal is linked to elevated anaerobic strength, an energy system that complements a rope climb. I wonder if this is what allowed me the extra burst of strength to push me to the top of the rope.2

There’s a fine line between anxiety and arousal, which can have positive influences on our physical prowess.

The Yerkes-Dodson Inverted-U Theory

In our everyday training, the notion of getting in the zone allows for the sports person, tactical athlete, and recreational gym goer to elicit the best possible results from their training. Though the science backs up this line of thought, we are all individuals and handle the physiological manifestation of arousal differently.3 Too much arousal and we face the prospect of crashing and performance levels decreasing. Too little and we don’t even get off the ground.

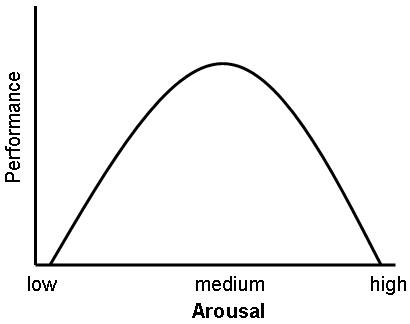

Figure 1

The Yerkes-Dodson inverted-U theory (pictured in figure 1 above) demonstrates that if an athlete can control his or her respective level of arousal without becoming over aroused and crashing, then he or she will perform at an optimal level. When applying this theory to a more general setting, we must remember that high levels of arousal can impact simple motor control through the physical manifestation of shaking and may have a negative effect on an athlete.4

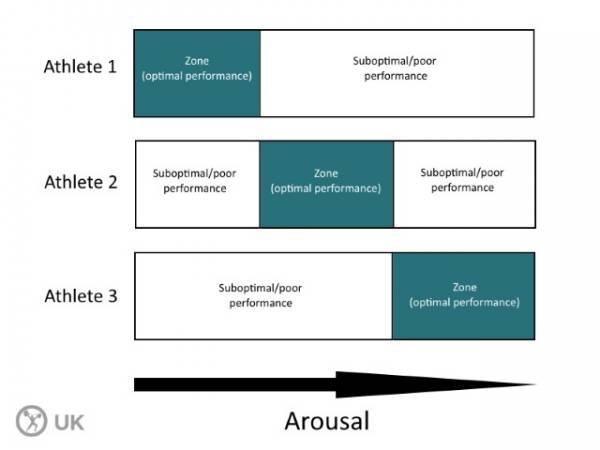

Figure 2

More recently the zone of optimal function (displayed in figure 2 above) has come into the limelight.5 This theory takes into account that not every athlete has a need for maximum anaerobic performance and may benefit from a lower and more sustainable arousal level.

But how can we control the effects of arousal? Where do you sit on this graph and how aroused do you need to become in order to perform optimally?

A New Perspective

We need to create a psychological perspective that has a positive impact on performance. As tactical athletes, sports personalities, or regular gym goers we must have a high perception of self-confidence, or self-efficacy.

“Turning these feelings into a display of physical dominance in one of the most physically and psychologically draining environments in the world is all about getting your mind state in check.”

In the words of the late Robin Williams in the film Hook, “Think happy thoughts.” You must apply a positive state of mind throughout any form of training or competition, regardless of outcomes. Take away what you can from each and every competition and training session. This is how we manage our mental state when undergoing training for admittance to elite military units. We have to remain positive and be safe in the knowledge that we are becoming fitter soldiers who can operate more effectively under stress in a combat environment.

In order to control arousal levels, and in turn enhance performance, we must have an “I will succeed” mind set. Do not doubt your ability to succeed. When I attended Commando training I was a young seventeen-year-old boy. My mental approach was to keep pushing forward, past the thirty-year-old seasoned soldiers who had taken seat on their gear in the pouring down rain and were feeling sorry for themselves. I used to enjoy watching people take themselves off course or voluntarily withdraw. The morality of this approach may be open to question. But passing someone who should be performing better than me allowed me to increase my self-efficacy, control arousal levels, and secure the coveted green beret.

Without the mindset to keep pushing forward, I never would have secured the green beret.

Mind Over Matter

This mind-over-matter approach is what makes or breaks your performance. We must learn to accept and appreciate what impact arousal has on performance. The physical manifestation of arousal displayed through butterflies, shakiness, and increased heart rate is not something to be afraid of.

Arousal can have a profound positive impact on our performance. Conversely, it can have a catastrophic effect when in the presence of cognitive anxiety. Our minds and bodies are clever systems and work in complete harmony. Trust your abilities, learn from your mistakes, and move forward. Train the mind and the body will follow.

More Like This:

- How to Manage Arousal Levels for Competitive Advantage

- Arousal Management: The Science Behind Getting Mad at the Bar

- Techniques for Controlling for Performance Anxiety

- New on Breaking Muscle Today

References:

1. Martens, R. Coaches Guide to Sport Psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1987.

2. Parfitt, C.G., Hardy, L., & Pates, L. “Somatic Anxiety, Physiological Arousal and Performance: Differential effects upon a high anaerobic, low memory demand task.” International Journal of Sport Psychology. 26, pp.196-213. 1995.

3. Apter, M.J. “Reversal theory and personality: A review.” Journal of Research in Personality. 18, 265-288. 1984.

4. Parfitt, C.G., Jones, J.G., & Hardy, L. “Multidimensional Anxiety and Performance.” Stress and Performance in Sport. Chichester, UK: Wiley. pp. 43-80. 1990.

5. Balk. A., Adriaanse. A., de Ridder. D., Evers. C. “Coping Under Pressure: Employing Emotion Regulation Strategies to Enhance Performance Under Pressure.” Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 35, 408-418. 2013.

6. Yerkes, Dodson. “The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation.” Journal of Neurological Psychology. (Figure 1), 1908.

7. Hanin, Y.L. “Emotions and athletic performance: individual zones of optimal functioning.” European Year Book of sports psychology, 1, pp. 29-72. (Figure 2), 1997.

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 courtesy of Jorge Huerta Photography.

Photo 3 courtesy of Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

Photo 4 courtesy of Breaking Muscle UK.

Photo 5 by LA(PHOT) A’BARROW/MOD [OGL], via Wikimedia Commons.