The shoulder is a complicated joint. Where most other joints are basically a single bone fitting into another bone, the shoulder is a complex interplay between your humerus, clavicle, and scapula. Your shoulder joint is also in some way controlled or affected by almost every muscle in your upper torso. Your pecs major and minor, lats, deltoids, rhomboids, and upper and lower traps represent the primary movers.

The shoulder is a complicated joint. Where most other joints are basically a single bone fitting into another bone, the shoulder is a complex interplay between your humerus, clavicle, and scapula. Your shoulder joint is also in some way controlled or affected by almost every muscle in your upper torso. Your pecs major and minor, lats, deltoids, rhomboids, and upper and lower traps represent the primary movers. In addition you’ve got your rotator cuff (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis) and your serratus anterior that play pivotal roles in shoulder stability. The complexity of this joint is what gives it its incredible range of motion and allows it perform all the various activities it’s capable of, from throwing a baseball or a punch to split jerking three hundred pounds and doing single arm handstands. The shoulder is a profoundly intricate joint. Unfortunately, it can also be a little high maintenance.

The Relationship Between Posture and Shoulder Impingement

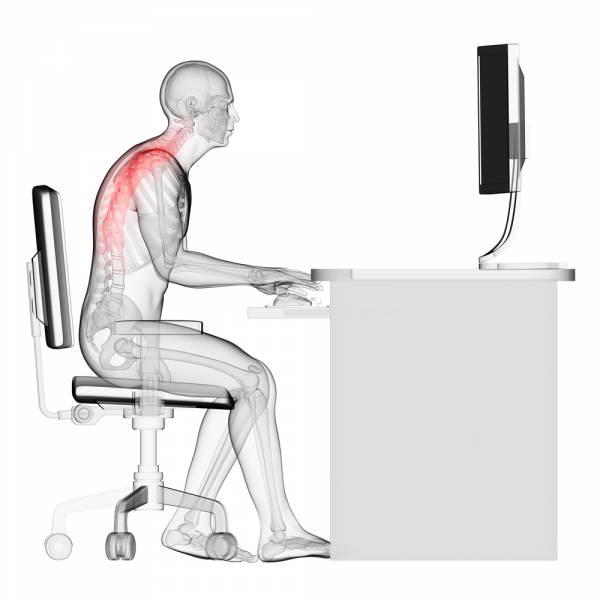

If you’ve read any of my articles then you know I’m a stickler for posture. Posture is the basis of proper movement and when your posture is messed up it short-circuits your athletic potential. It may not be the case with every individual, but my experience has been that most movement disorders originate not with the way we move during our one hour of exercise per day, but rather the way we hold our body the remaining twenty three.

Shoulder impingement is one of the most common postural issues, and anterior shoulder pain is often a sign of some degree of shoulder impingement. While this is a valid assumption, to me, impingement isn’t a valid diagnosis. It’s the musculoskeletal equivalent of “diagnosing” someone with a cough. There are treatments for a cough. There’s an entire aisle at your pharmacy full of cough remedies, and likewise, the most common treatment option for shoulder impingement remains something along the lines of, “Take an aspirin and rest.” But impingement, like a cough, is a symptom of a larger problem. There is certainly something to be said for managing symptoms, but the problem is never truly solved until it’s dealt with at its source.

How Shoulder Impingement Happens

Impingement occurs when the bony structures of your shoulder (particularly the acromion) begin to compress the bursa (a lubricating sac on top of the rotator cuff) and the underlying tendons. The differential diagnoses for impingement are myriad: rotator cuff issues, shoulder weakness, shoulder instability, bicep tendonitis/tendinosis, etc.

Frequently shoulder impingements will be treated as rotator cuff weakness, particularly in the external rotators. The logic goes something like this: If your arms are internally rotated, it must be because the internal rotators are shortened and the external rotators are lengthened and weak. Therefore, if you strengthen the external rotators the problem will resolve itself. Right? Well, no, not really. Impingement will absolutely cause rotator cuff weakness and frequently, when left untreated, will lead to rotator cuff and labral tears. Even so, none of this is evidence that the problem must be the rotator cuff.

What if you asked a friend of yours to perform a task for you, but before you even showed them the task you blindfolded them? Regardless of how capable or incompetent they may be, it’s unlikely they could successfully learn and execute the task while wearing a blindfold, although it’s possible they may figure out some sort-of similar, blind-man’s approximation. This is basically what’s going on with your rotator cuff. If your scapula is moving poorly or in a bad position, your cuff can’t fire correctly. It’s flying blind. Restoring proper function to your scapula can help remove the blindfold. You might still have some cuff strengthening to do, but correcting the scapulae should be step one.

Impaired Movements From Impingement

The two most common physical manifestations of impaired movement that I see are abducted scapulae and internally rotated humeri. That’s a fancy way of saying your scaps have shifted away from your spine and your shoulders are twisted down and forwards. Can you guess what position this is probably a result of? (Hint: it has to do with sitting.) Much like common dysfunctions at the hip, the problem is often anterior tightness secondary to over-activation of the anterior musculature coupled with posterior weakness from being lengthened all the time. Seems a good approach would be to mobilize the tight stuff and strengthen the weak stuff. Let’s start with mobility.

Step #1: Mobilize the Pecs

The first common area of anterior tightness is the pecs, both the pec major and minor. Now I know stretching has been kind of vilified in the fitness media as of late because it shuts off the muscle you’re stretching (which is bad for maximal force production), but what if you want the muscle to turn off, potentially in a situation where it’s been chronically over-firing? In this case, I think stretching is pretty fantastic.

My two favorite pec stretches are the door stretch and the foam roll pec stretch. To perform the door stretch stand in front of a doorway and raise your arms to just below shoulder height, palms forward. Now step into the doorway, allowing the doorjamb to press against your hands (or wrists, or whatever part of your lower arm is making contact) and push them backwards, eliciting a stretch along the pecs. This stretch can also be performed with your elbows bent at ninety degrees or one shoulder at a time for a more intense stretch. Hold for three sets of thirty to sixty seconds.

The foam roll pec stretch is a bit more passive and as such probably better at eliciting total relaxation. Lay down on top of a foam roller lengthwise with your head and pelvis supported on the foam roller. Now put your hands directly out in front of you like you’re doing the Hulk clap. From here, let your arms fall to your sides. Don’t let your shoulders ride up towards your ear, maintain a good position. You should feel a stretch in your pecs as your arms get lower. You can also place the foam roller on top of a table or bench so your hands can get below where the floor would be and increase the stretch further.

Another good option for mobilizing the pecs is a lacrosse ball. Stand facing a wall. Place the ball on top of your pec and lean into the wall, forcing your bodyweight onto the ball. Now you just have to kind of smash around in your pec until you find areas of tightness. You can either lean on them and consciously try to relax them away or, when you find a particularly bad spot, you can move your arm around while keeping your pec pinned with the ball to floss the tissues a bit. If you can find a corner to lean on so your arm can move freely past the wall, even better. Do this for two or three minutes per pec.

Step #2: Mobilize the Lats

The next mobilization target area is your lats. If you’re having trouble getting your arm into end-range flexion, then it makes sense to mobilize the muscle responsible for moving your shoulder the other way (extension), right? The tool of choice is going to be the foam roller.

A good lat stretch involves getting into the same position on top of the roller as you did for the pec stretch, but instead of letting your arms fall to the side, let them fall overhead. The key is contracting your abs and to keep your lower back flush with the roller. When we’re missing end-range shoulder flexion, frequently we’ll make up for it with lumbar extension, which is bad all around. By flexing your abs you lock your lumbar region in place and ensure the stretch is in the lats. Many people find that the weight of their arms is not enough to elicit a stretch, as the lat is a pretty big muscle. If this happens you can either hold onto a weight plate, a barbell, or a band, or have a friend apply gentle pressure to your arms until you feel the stretch. Again, try this for three sets of thirty to sixty seconds.

You can also smash your lats with a foam roller or lacrosse ball. Try to find areas of tightness and either relax them away with constant pressure or pin down the tissues and floss them by moving your arm. You’re trying to mobilize flexion, so moving into flexion would be the recommended method of flossing here.

Step #3: Strengthen the Weak Stuff

Hopefully you’ve restored some motion to those tied-up tissues around your shoulder. Now you’ve got to strengthen the opposing muscles to help maintain the new positions. The main target areas here are the rhomboids and lower traps, the muscles responsible for pulling your scapulae together and down.

Prone Ts and Ys are a great way to build initial strength. You can start with prone Ts and Ys on a table or bench and then progress to prone over a physioball. A row with lower trap emphasis can be performed by rowing from a high fixed point (head height or higher) and pulling down to your ribs with a strict focus on keeping the shoulders down and back. It may also be useful to perform these exercises unilaterally, as one scapula might be more jacked up than the other (weirdly enough it’s typically your dominant side.) Perform each exercise for three or four sets of eight to ten repetitions. Err on the side of too light rather than too heavy. It’s all about proper form here.

Just like with your hips, the best medicine for your ailments is often prevention. Learning how to achieve and maintain a healthy and stable position at your shoulders trumps all else. Sometimes we just need a little assistance in learning those basics.

Check back next time when I’ll be attacking the upper trap and serratus, two more of the usual suspects involved in shoulder impingement and instability.

Photo 1 by National Institute Of Arthritis And Musculoskeletal And Skin Diseases (NIAMS) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo 2 courtesy of Shutterstock.