In the spring of 2007, I received word that I had landed a summer position as a wilderness ranger in California’s Sequoia National Forest. I was also playing the best lacrosse of my life for Georgetown University, and I knew if I wanted to stay on the field that I’d have to spend the majority of the upcoming summer training. I had a big decision to make. Should I pursue my passion for the wilderness or remain in civilization to train all summer for my upcoming season? The previous year, a friend from the United States Naval Academy had introduced me to CrossFit. After consulting with my strength coach and watching Rocky, I knew I already had the answer.

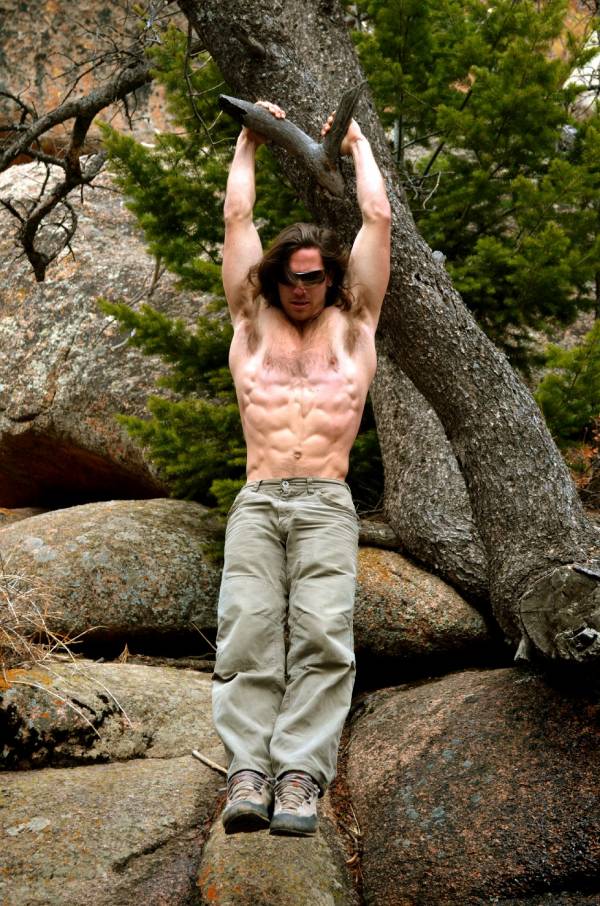

During my first wilderness tour, I spent all of my free time constructing an all-natural CrossFit gym at my summer base camp. I made a combination squat rack and dip station out of logs and stumps, gathered every shape and size of rock for weights, discovered cliffs I could use to do handstand pushups, and organized fallen trees as box jumps. Surprisingly, it was difficult to find tree branches low enough to do pull ups on, so I tied a rope to a branch and looped it around a nook in a tree. This setup looked and functioned like a trapeze-pull up bar and added some excitement to workouts. But this outdoor gym did more than just get me into the best shape of my life – it changed the course of my life.

If you threw any WOD at this “wild gym,” you were good to go. I remember doing “Fran” with a heavy rock for thrusters and pull ups on a very dynamic pull up bar (all at 9,000 feet in elevation). Another favorite was “Nancy.” I would do overhead squats with a log (that I hoped was not more than 95 pounds) and then 400m sprints on a muddy, rocky, uneven trail. This made for great agility training. I had light, medium, and heavy logs that I used for back squats, front squats, and overhead squats. I placed rocks on my back or in my backpack to add weight to pull ups, pushups, and dips. Working out had truly become an adventure.

The most epic day of wild-fitness began with ten miles of hiking to get to several trees that had fallen across the trail and needed to be sawed. After several hours of sawing and swinging axes, we headed back to camp. I had a quick snack and decided to do some pull ups and dips for a little extra work. I felt pretty accomplished with my day and was looking forward to the several bratwursts waiting for me in my backpack.

The most epic day of wild-fitness began with ten miles of hiking to get to several trees that had fallen across the trail and needed to be sawed. After several hours of sawing and swinging axes, we headed back to camp. I had a quick snack and decided to do some pull ups and dips for a little extra work. I felt pretty accomplished with my day and was looking forward to the several bratwursts waiting for me in my backpack.

Just as I sat down and started to gather firewood, a sixteen-year-old boy ran into camp yelling, “My mom is having a heart attack!” With my calves twitching and adrenal hormones pumping, I sprinted down the trail with a first-aid kit and radio. The boy’s mother was sitting by the trail and was relieved to see a potential rescuer. After an initial assessment, we determined she had a severe case of altitude sickness. The rescue helicopter arrived and landed in a dangerously small meadow. We loaded her up and held our breath until they cleared the canopy and headed towards civilization. Her son was still with me and I ended that day with another six miles of hiking. Preparing for the unknown and unknowable. I slept well that night.

Sleep was the best part of being in the wilderness. It became much more of a natural rhythm that flowed perfectly each day. When it got dark, you went to bed. When the sun came up, you got up. I received a healthy dose of daily sunlight and avoided any of the artificial light pollution that invades so much of our lives. You know that sickly orange glow from street light that trickles through the blinds at night? None of that in the wilderness. The only interruption was the occasional deer running through camp at 2:00am, in which case I generally awoke thinking I was under certain bear-attack. The fight-or-flight response is paleo, right?

You squat a lot in the wilderness. Getting water, squat. Stoking the campfire, squat. Making dinner, squat. Bathroom, squat. It’s interesting how the modern world has practically eliminated the need to go through such an innate human movement. If you’re having trouble going below parallel, try going backpacking for a week.

You squat a lot in the wilderness. Getting water, squat. Stoking the campfire, squat. Making dinner, squat. Bathroom, squat. It’s interesting how the modern world has practically eliminated the need to go through such an innate human movement. If you’re having trouble going below parallel, try going backpacking for a week.

Hiking is another activity that is crucial for human vitality. Consistent times of low-intensity movement throughout the day will help you recover faster, improve mobility and make you healthier. An interesting phenomenon that I’ve seen develop is the sedentary athlete. This individual trains exceptionally hard and is at a relatively high level of fitness. However, even though he or she goes all-out for a one-hour workout, the rest of the day involves nothing but sitting. We need to move constantly. The circulation of our venous blood and lymphatic fluid is not under pressure like our arteries. These systems require muscular contractions to push fluid along. If we are inactive for extended periods of time, this fluid begins to pool and slows down the clearance of metabolic waste.

Perpetual movement does not mean you have to work out all day long. Take a quick walk or bust out a few squats, lunges, or push ups at your desk, several times a day, and suddenly you are moving things along. As a CrossFit coach, I’ve noticed how low-intensity movement affects me. On days that I train hard and coach multiple classes, I am physically tired, but do not feel as sore or stiff as I do on days I train and then sit at a computer for extended periods. We’ve become so focused on the one-hour of high-intensity exercise that we forget to move the remaining 23.

Living in the wilderness and using nature as my gym truly changed me and my philosophy on training. I think that CrossFit has done an outstanding job of disrupting the outdated social agreement that exercise needs to be done using machines under fluorescent lights and ended with thirty minutes of cardio. I believe we should take this a step further, though and turn fitness into an adventure.

Living in the wilderness and using nature as my gym truly changed me and my philosophy on training. I think that CrossFit has done an outstanding job of disrupting the outdated social agreement that exercise needs to be done using machines under fluorescent lights and ended with thirty minutes of cardio. I believe we should take this a step further, though and turn fitness into an adventure.

You do not always need rubber flooring, bumper plates, air conditioning, 24” boxes or a pre-workout supplement to work out. Mother Nature has provided everything we need and more. Let’s embrace this. Go get hot, dirty, and uncomfortable while loving every second of it. Go alone to somewhere no one will see you, or even believe you were there if you told them, and do a workout.

I believe that we were all born wild and that this wildness is still a part of who we are, both as individuals and as a culture. I also believe that outdoor exercise can be a means to reconnect to the innate wildness in all of us. Challenge yourself, workout anywhere, and live with wildness, passion, and purpose.

Photos courtesy of Dan Vinson and The Wild Gym.